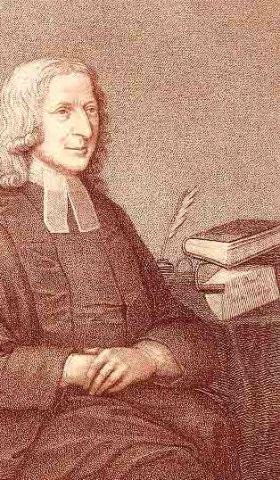

John Wesley lived by the Bible and claimed to be a man of one book (homo unius libri). But his single-minded focus on Scripture did not result from failing to read other books. It was something he achieved on the far side of wide reading and much learning. Wesley knew how to learn from Christians of all ages and denominations, and he wanted to pass that privilege along to as many people as he could.

As a result, Wesley spent considerable time editing and publishing books that he considered helpful. He wanted his people to be reading widely in the best works available. In 1750 he brought out a fifty-volume set of books called A Christian Library. The sub-title was “Extracts from and Abridgments of the Choicest Pieces of Practical Divinity Which Have Been Published in the English Tongue.” I’m sure dissertations have been written about what he chose and how he chose it, but a quick look shows that he was not trying to find simply the best or most important books in the history of Christianity. He mostly ignores the church fathers (represented only by the apostolic fathers and Macarius), the great medieval scholastics, and the reformers. Instead, he focuses on recent centuries (from as far back as the sixteenth up to his contemporaries like Jonathan Edwards in the eighteenth), English works (including both Puritans and Established churchmen who took turns persecuting each other), and above all, “Practical Divinity.” Wesley does include works originally written in German, French, Spanish, and Latin, but all Englished and already influential in his homeland.

The collection is bracingly diverse and refreshingly nonpartisan. The works of Arminius are absent from this collection by an arminian and editor of The Arminian Magazine. Wesley rejected the idea of limited atonement, but includes copious writings by Thomas Goodwin (pro limited atonement) while omitting John Goodwin (anti limited atonement). Why? Thomas Goodwin wrote some of the “choicest practical divinity in the English tongue,” that’s why. I don’t care if you were a member of the Westminster Assembly, if you can write The Heart of Christ in Heaven toward Sinners, only an anti-Calvinist bigot could refuse to recommend your book. John Wesley knew that fifty volumes was hardly enough space to exhaust the great central core of Christian truth and its outworkings in the human heart.

I haven’t read all of A Christian Library, and a handful of the volumes strike me as moralizing sermons from British clergyman who might have wandered in out of a Jane Austen novel. But just a handful, and that may be too flippant a dismissal of the less exciting volumes. Wesley’s judgment is so demonstrably keen that he deserves the benefit of the doubt as an editor. Undeservedly obscure writers like Bishop Ken, Isaac Ambrose, and Robert Leighton are spiritual powerhouses, and Wesley has selected some of their best work. There’s a revival of interest in John Owen lately, but several of his greatest books (Communion with God!) are reprinted here in Wesley’s Christian Library. Anybody who thinks of Owen and Wesley as opposites who could never meet ought to spend a little more time reading Owen and Wesley.

Here’s great news: The Wesley Center for Applied Theology has scanned John Wesley’s entire Christian Library and made it available online. The text they scanned was an 1821 reprint in thirty volumes, and there are plenty of signs that robots did the work and human editing hasn’t happened yet: a character named Jesus Cubist shows up on one page. But give them time, or send them money, or just take up and read, already.

John Wesley’s Christian Library:

Volume 1: The Apostolic Fathers, Macarius of Egypt, Johann Arndt’s True Christianity.

Volume 2: Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

Volume 3: More Foxe’s Martyrs, with supplements

Volume 4: More Foxe supplements, Bishop Hall’s Meditations, extracts from Robert Bolton.

Volume 5: more Bolton, John Preston.

Volume 6: more Preston, Richard Sibs, Thomas Goodwin.

Volume 7: more Goodwin, William Dell, Thomas Manton, Isaac Ambrose.

Volume 8: more Isaac Ambrose (Looking Unto Jesus).

Volume 9: more Ambrose, Jeremy Taylor, Francis Rouse’s Academia Celestis, Ralph Cudworth, Nathanael Culverwell.

Volume 10: more Culverwell, John Owen (Mortification of Sin, Christologia, Communion with God).

Volume 11: More Owen, John Smith.

Volume 12: Herbert Palmer, extracts from The Whole Duty of Man, William Whateley, sermons of Bishop Robert Sanderson.

Volume 13: James Garden’s Comparative Religion,

Volume 14: Pascal’s Pensees, John Worthington’s Self-Resignation, Bishop Ken’s Exposition of the Catechism.

Volume 15: Lives of Eminent Christians, chiefly extracted from Clark.

Volume 16: Life of Bishop Bedell, Life of Archbishop Butler, Letters of Samuel Rutherford, Anthony Horneck’s Happy Ascetic and Lives of Primitive Christians.

Volume 17: works by Hugh Binning, Matthew Hale, and Simon Patrick’s Christian Sacrifice.

Volume 18: Richard Allen (Vindication of Godliness, Rebuke to Backsliders, Necessity of Godly Fear)

Volume 19: Dr. Cave’s Primitive Christianity, Bunyan’s Holy War, Stuckley’s Gospel-Glass.

Volume 20: Cowley’s Essays, Goodman’s Evening Conference, works by Robert Leighton, Bishop Beveridge.

Volume 21: works by Isaac Barrow, John Brown, Antoinette Bourignon’s Solid Virtue, sermons by Mr. Kitchen and Mr. Pool.

Volume 22: Richard Baxter’s Saint’s Everlasting Rest, Edward Crane’s Prospect of Divine Providence,

Volume 23: Fenelon, Molinos, Henry More, Stephen Charnock, Dr. Calamy, Henry Scougal.

Volume 24: Sermons by Dr. Annesley, Richard Lucas’ Inquiry after Happiness.

Volume 25: sermons of Bishop Reynolds, devotions.

Volume 26: Sermons of Dr. South, Young, Howe’s Thoughts, Juan d’Avila, the anonymous Parson’s Advice,

Volume 27: works by Archbishop Tillotson, John Flavel’s Husbandry Spiritualized, Lives of Sundry Eminent Persons.

Volume 28: Life of John Howe, The Living Temple, Philip Henry, George Trosse, John Eliot.

Volume 29: more Eminent Persons, Alleine’s Letters, Francke’s Nicodemus.

Volume 30: Norris on Christian Prudence; Edwards on Revivals of Religion; Religious Affections.