You have to really care about a book if you set out to translate it for the very purpose of arguing against it. There’s just no way to make a decent translation without getting your hands dirty, your mind filled with the original text, your own vocabulary relativized by an alternative system, and your attention drawn to a vast number of intricate details.

You have to really care about a book if you set out to translate it for the very purpose of arguing against it. There’s just no way to make a decent translation without getting your hands dirty, your mind filled with the original text, your own vocabulary relativized by an alternative system, and your attention drawn to a vast number of intricate details.

Thomas Burman (recently appointed Director of Notre Dame’s Medieval Institute) makes this point in a brief autobiographically-framed essay, “The Spacious Ironies of Translation” in New Centennial Review 16:1 (Spring 2016), 87-92.

Burman reports a couple of massive translation projects carried out in the middle ages, which were specifically designed by Christians for the refutation and overthrow of Jewish and Muslim theological claims. One of them is the Pugio Fidei (Dagger of Faith), which Burman calls “the most linguistically recondite monument of the Latin Middle Ages” by “the finest Semitic linguist in Christian Europe since Jerome and before the sixteenth century,” the Dominican friar Ramon Martí (fl. 1250–84).

The “dagger” was intended, Burman freely acknowledges, to “cut the throat of Jewish perfidy,” so anybody reading it should know right up front that it is an exercise in polemical anti-Jewish argumentation. What Burman notes, however, is the irony to which his title draws attention: Martí so thoroughly immerses himself in Hebrew sources and patterns of construal that he behaves oddly like a devotee:

We think we have a sense of what Martí is up to, for he tells us in no uncertain terms: he’s cutting Jewish jugulars, ferociously attacking Jewish belief, snidely mocking rabbinical exegesis of the Hebrew Bible. But while he is up to this, we find him doing something else that feels so very different—endlessly lavishing attention on Jewish texts, every detail of which fascinates him, every vowel point of which he insists on recording in minute detail, every grammatical nicety of which he works diligently to capture.

Another example:

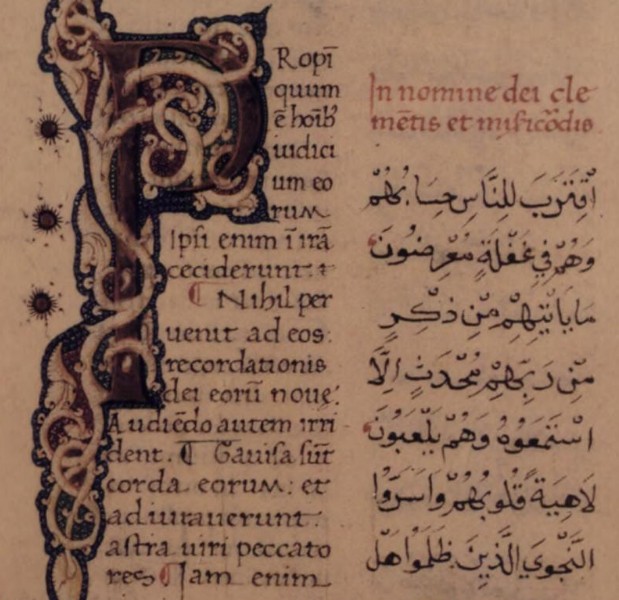

Three centuries later, the remarkable Juan de Segovia would orchestrate a trilingual edition of the Qur’an—Arabic original alongside Castilian and Latin translations—the greater part of which has been lost. But in the rambling preface that does survive, we see much the same thing, a Christian laboring to make Islam’s holy book available in painstakingly accurate versions so it can be refuted, but who in consequence finds himself poring over Arabic Qur’an manuscripts, whose language he finds captivating, and whose paleographical conventions charm him—all those beautiful green and red diacriticals!

There is a vast difference between arguments that take place at a distance and arguments that take place up close. Translation for the sake of refutation is a kind of disagreement that takes place in such close quarters that it has an altogether different character.