“Sudden Heaven” describes an experience of glory, glory in the course of normal life. A moment of sudden heaven is not marked by any outward circumstances (it’s not sparked by graduation or a touchdown or falling in love), but is an unexpected, unexplainable epiphany in the middle of the commonplace. You’re just going on with life, and for no apparent reason an eternal power “picks you up and rings you like a bell,” to use Annie Dillard’s phrase. Nothing changes, but sudden heaven blazes. In the elegant phrase “sudden heaven,” it’s the word “sudden” that captures the inbreaking, while “heaven” captures the otherworldliness, the eschatological, the end and consummation of the world making itself known.

I can’t be sure who coined the term, but I’ve found it used by four poets: Ruth Pitter, C. S. Lewis, Walter de la Mare, and Terry Scott Taylor. These poets are connected to each other by various threads of influence, so the phrase “sudden heaven” has been passed around inside of this little school. Ruth Pitter seems to be the furthest upstream, so I tend to credit her as the source for the others. They ring the changes on Pitter’s poem. Here’s the plot as far as I can follow it.

Ruth Pitter (1897-1992) was a British poet who wrote in a solid and deeply traditional style. An adult convert to Christian faith, Pitter wrote poetry both before and after her conversion. Though Pitter enjoyed considerable fame during her career, her name seems to have slipped into obscurity since.

Here is Ruth Pitter’s poem, “Sudden Heaven,” from her 1936 book A Trophy of Arms:

Sudden Heaven

All was as it had ever been—

The worn familiar book,

The oak beyond the hawthorn seen,

The misty woodland’s look:The starling perched upon the tree

With his long tress of straw—

When suddenly heaven blazed on me,

And suddenly I saw:Saw all as it would ever be,

In bliss too great to tell;

For ever safe, for ever free,

All bright with miracle:Saw as in heaven the thorn arrayed,

The tree beside the door;

And I must die—but O my shade

Shall dwell there evermore.

It’s a brilliant little 4-stanza poem, built around the contrast between “all… as it had ever been” (first stanza) and “all as it would ever be” (third stanza). You can almost hear a rushing wind build up in the poem’s second half as it begins repeating words in wave-like rhythmic patterns: “I saw, saw all, all bright;” “ever, for ever, for ever, evermore.” Between the straw and mist of the first half, and the bliss and miracle of the second half, there intervenes the unforeseen event: “suddenly heaven blazed on me, and suddenly I saw.” This is a great piece of work, capable of taking any sympathetic reader right to the threshold of the ineffable experience which, in the final analysis, you have either had or have not had.

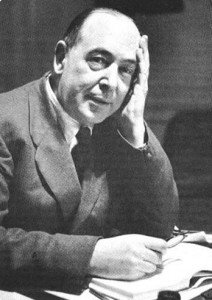

C. S. Lewis uses the phrase “sudden heaven” in the memorable final line of one of his poems. I can’t say when this poem was written because Lewis’ poetry is only available in the uncritical, mostly dateless Walter Hooper-edited volume. But Lewis and Pitter exchanged many letters in the 1940s and later, and Lewis was especially familiar with the Trophy of Arms volume in which “Sudden Heaven” appeared.

C. S. Lewis uses the phrase “sudden heaven” in the memorable final line of one of his poems. I can’t say when this poem was written because Lewis’ poetry is only available in the uncritical, mostly dateless Walter Hooper-edited volume. But Lewis and Pitter exchanged many letters in the 1940s and later, and Lewis was especially familiar with the Trophy of Arms volume in which “Sudden Heaven” appeared.

Here is how Lewis builds a poem toward the phrase:

The Day with a White Mark

All day I have been tossed and whirled in a preposterous happiness:

Was it an elf in the blood? or a bird in the brain? or even part

Of the cloudily crested, fifty-league-long, loud uplifted wave

Of a journeying angel’s transit roaring over and through my heart?My garden’s spoiled, my holidays are cancelled, the omens harden;

The plann’d and unplann’d miseries deepen; the knots draw tight.

Reason kept telling me all day my mood was out of season.

It was, too. In the dark ahead the breakers only are white.Yet I —I could have kissed the very scullery taps. The colour of

My day was like a peacock’s chest. In at each sense there stole

Ripplings and dewy sprinkles of delight that with them drew

Fine threads of memory through the vibrant thickness of the soul.As though there were transparent earths and luminous trees should grow there,

And shining roots worked visibly far down below one’s feet,

So everything, the tick of the clock, the cock crowing in the yard

Probing my soil, woke diverse buried hearts of mine to beat,Recalling either adolescent heights and the inaccessible

Longings and ice-sharp joys that shook my body and turned me pale,

Or humbler pleasures, chuckling as it were in the ear, mumbling

Of glee, as kindly animals talk in a children’s tale.Who knows if ever it will come again, now the day closes?

No-one can give me, or take away, that key. All depends

On the elf, the bird, or the angel. I doubt if the angel himself

Is free to choose when sudden heaven in man begins or ends.

Lewis’ poem probes deeper into the psychological impact of the experience, suggesting that “fine threads of memory” reach deep down to “diverse buried hearts” and “transparent earths” with “shining roots” of “luminous trees.” He is affectedly agnostic about the source of this feeling: an elf, a bird, an angel, whatever. There is less to go on here than even in Pitter’s poem, as far as the source of the experience is concerned. But Lewis does more with the effects of sudden heaven passing through him, unifying his fragmented life in a rush of elation that binds the boys he used to be with the men he has been more recently, and giving his distended life back to him whole. Though it’s only hinted at in this poem, we have the benefit of Lewis’ other writing to let us know that he thought heaven worked this way: the simultaneous possession of the moments of a complete life.

The third poet to get his hands on “sudden heaven” is Walter de la Mare (1873-1953). Though he is a poet in his own right, the use he makes of “sudden heaven” is not in a composition of his own but in an anthology. In 1939, de la Mare published Behold This Dreamer! which had the subtitle, Of Reverie, Night, Sleep, Dream, Love-Dreams, Nightmare, Death, the Unconscious, the Imagination, Divination, the Artist, and Kindred Subjects. De la Mare prints Pitter’s poem on pages 655-656, near the end of his large anthology in a section called “Animus and Anima.”

It may not seem worth bothering to mention an anthologist’s use of the poem, but Walter de la Mare was no ordinary anthologist. He had a scheme in mind. His imagination was so powerful that he could fill a 700-page volume with extracts from other writers, and the resulting work was a creative statement of his own point of view. To immerse yourself in a Walter de la Mare anthology (he edited several, most famously the early Come Hither) is to be brought into the world as de la Mare sees it. The critic Lord David Cecil said:

De la Mare’s anthologies should be numbered among his creative works; for in them the quoted passages are woven together on a web of imaginative comment as highly wrought and as often as long as the quotations themselves; so that the whole emerges less as a collection of other men’s writings than an expression of the thoughts aroused in the anthologists by these writings, and coloured by the mood in which he read them. These anthologies represent a new literary form invented by Mr de la Mare, which he has employed as yet another mode to express his unique vision of reality.

In de la Mare’s Behold This Dreamer!, Pitter’s poem is re-contextualized as part of a discussion of passivity and activity in creative work. What de la Mare wants to know is, do visions just happen to us, or do we work for them? He is fixated on the notion that much of our existence is not a life that we lead, but a life that we follow. Pitter’s “Sudden Heaven” is called to the witness stand to testify to that.

The final link in this chain of poets is the kind of modern poet who writes song lyrics, singer-songwriter Terry Scott Taylor. In 1986 his band Daniel Amos released an album entitled Fearful Symmetry. The album is a dreamlike blending of verbal imagery and synthesized sounds, rambling and evocative, high-pitched and trebly as if mixed by angels from the ’80s. But the song entitled “Sudden Heaven” stands out from the album sonically. Instead of synthesized keyboards and drum machines, this song fades in with a cartoony string plunking, crashing through with a rebel yell and the cacophany of a barely coordinated 4-piece rock band playing country music like punk rockers with a grudge. Terry Taylor’s vocal comes in and delivers his own re-writing of the Pitter poem:

Sudden Heaven

Familiar scene, no dream, I look

‘Cross hills of green and woodland brookThen, pulse for pulse The Will speaks soft and low

On waves of joy the sweet and tearful flowSudden heaven has blazed on me

Sudden heaven has blazed on me

I am taken up, I am shaken up (sudden heaven)

Where the angels praise, In the brilliant daze (sudden heaven)

Sudden heaven has blazed on meBlack map of woe, dark hungry night

Here in my soul I stop the flightThe ivy taps upon the window pane

I won’t resist the One who calls again

Sudden heaven has blazed on me

Sudden heaven has blazed on meBliss too great to tell, Bright with miracle (sudden heaven)

As it would ever be, Safe, forever free (sudden heaven)

Sudden heaven has blazed on meMy Lord, how long will heaven keep

The days beyond the midnight sleep?Sudden heaven has blazed on me, yeah

Sudden heaven has blazed on me, yeah

Blazed on me, yeah

The song is an obvious re-writing of Pitter’s poem, but Terry Taylor has re-written it from within, so to speak. He confidently fills in gaps, connects lines with his own verbage, and re-combines Pitter’s imagery to make it work in the pop-song format with a verse-verse-bridge-verse-coda structure.

Taylor’s use of the song, by the way, is mediated through Walter de la Mare’s anthology rather than coming straight from Pitter. Behold This Dreamer! also prints a Christina Rossetti poem, “Echo,” with the lines “Come back to me in dreams that I may give / Pulse for pulse, breath for breath…”, which shows up in the third line of the song. And the “ivy tapping on the pane” is from an obscure poem entitled “The Haunted House,” by Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, printed on page 285 of de la Mare’s book. Terry Taylor seems to have composed the entire album Fearful Symmetry by a kind of creative re-combining of the lines anthologized by de la Mare. As in this case, he sometimes subverts de la Mare’s own intentions and reconnects with the original author’s aims. Other times he loots poems for phrases to be put to his own uses. I don’t know of another example of such masterful collage workmanship producing a finished artwork with its own integrity besides perhaps Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner (as anatomized by the critic Lowes who found practically every line in contemporary travel literature).

Given the explosive nature of the musical setting, Taylor has to get to the point as soon as possible, so he telescopes the slow build-up of Pitter’s composition into two lines and then narrates the inbreaking of the vision: “Then, pulse for pulse The Will speaks soft and low / On waves of joy the sweet and tearful flow / Sudden heaven has blazed on me … I am taken up, I am shaken up… where the angels praise, in the brilliant daze.” Terry Taylor’s song is more explicit about the nature of the eschatology, specifying it as a vision of the glory of God which is seen by angels and will be seen by believers after death. Some of Pitter’s evocative power is sacrificed (“all as it shall ever be”), but a solidity of allusion is gained, which works well in a musical setting.

The Pitter phrase “sudden heaven” is a great little coinage. It grabbed the attention of Lewis, de la Mare, and Taylor, and through them it caught my attention. It’s all about attention, and how it is caught, and what does the catching. What does the catching is eternal life, the kind of eternal life that gives you back yourself in an act of unanticipated free grace. Suddenly she saw all as it would ever be, all bright with miracle, and her shade shall dwell there evermore.