Introduction

George Herbert was born on April 3, 1593, one of ten children. Though his father died when he was only three years old, Herbert’s mother, Magdalen, took responsibility for the education of her children. Moreover, she was decently well-connected, in that she ran a kind of literary and academic salon; that is, she managed a room used for the reception of guests that became a gathering place of Oxford University professors and dons and literary figures, including the poet John Donne. George Herbert’s biographer Izaak Walton writes, “her great and harmless wit, her cheerful gravity and her obliging behaviour gained her an acquaintance and friendship with most of any eminent worth or learning, that were at that time in or near that University; and particularly with Mr. John Donne.”[1]John Tobin, ed., George Herbert: The Complete English Poems (London: Penguin Books, 1991), 271. Magdalen Herbert and Donne’s friendship is commemorated in Donne’s poem “The Autumnal,” wherein he writes of Magdalen’s beauty: “No Spring, nor Summer Beauty hath such grace/As I have seen in one autumnal face” (ll. 1-2): and of her mind, “In all her words to every hearer fit,/You may at revels, or at council sit” (ll. 23-24).[2]A. J. Smith, ed., John Donne: The Complete English Poems (London: Penguin Books, 1971), 105.

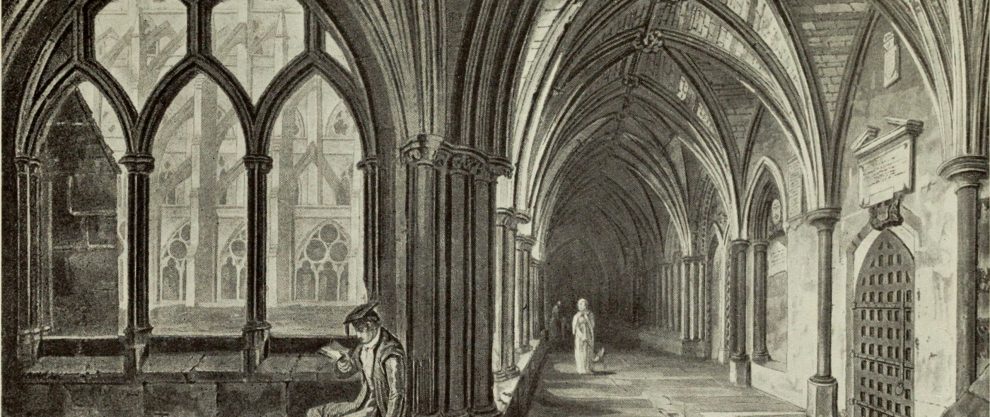

As a child Herbert was tutored at home but he began attending the Westminster School in London when he was twelve, gaining proficiency in Latin and Greek, as well as in choral singing, for the students at the school provided music for liturgical services at Westminster Abbey, which was next door.[3]On choirs at Westminster Abbey in general see Edward Pine, The Westminster Abbey Singers (London: Dennis Dobson, 1953). He then proceeded to study at Trinity College, Cambridge. At both Westminster and Trinity College, Herbert showed himself to be a good student with a demeanor comparable to the angels, it appears. Walton writes, at school “the beauties of his pretty behaviour and wit shined and became so eminent and lovely in this his innocent age, that he seemed to be marked out for piety, and to become the care of Heaven, and of a particular good Angel to guard and guide him.”[4]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 270.

At twenty-three years of age Herbert was made a Fellow of Trinity College, entrusted with teaching younger undergraduates Greek, rhetoric and oratory. At the same time, however, Herbert, who had a fragile constitution, was often sick and struggled to make ends meet, especially given his need to purchase books. To supplement his income he took of the role of Public Orator at the university, a role that increased his social contacts, including with members of the court of King James I, Francis Bacon and the Anglican bishop Lancelot Andrewes. As a college Fellow at Cambridge, Herbert was expected to become a priest in the Church of England, which was not much of a demand given that he was a devout, practicing Anglican. But, in his early 20s, Herbert had his mind set on a career in government so he became a Member of Parliament, an election he easily procured due to the fact that his mother had married Sir John Danvers, himself a Member of Parliament. Unfortunately, or, perhaps fortunately for us, several of Herbert’s political supporters died in quick succession, leaving him with little room for advancement in government, according to Walton. Herbert’s autobiographical poem “The Affliction (I)” suggests, however, that Herbert experienced what we might call a “conversion” from a secular life in government to a life of service in the Church:

When first thou didst entice to thee my heart,

I thought the service brave;

So many joys I writ down for my part,

Besides what I might have

Out of my stock of natural delights,

Augmented with thy gracious benefits.

I looked on thy furniture so fine,

And made it fine to me;

Thy glorious household-stuff did me entwine,

And ‘tice me unto thee.

Such stars I counted mine: both heav’n and earth;

Paid me my wages in a world of mirth.

What pleasures could I want, whose King I served,

Where joys my fellows were?

Thus argued into hopes, my thoughts reserved

No place for grief or fear.

Therefore my sudden soul caught at the place,

And made her youth and fierceness seek thy face.[5]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 41.

Thus, at thirty-one years old, Herbert decided to pursue holy orders in the Church of England.

Influences on George Herbert

The great twentieth-century poet T. S. Eliot points to four people who had an undeniable influence on Herbert’s spiritual development, leading him to become a priest: his mother, John Donne, the aforementioned Lancelot Andrewes, and Nicholas Ferrar of the Little Gidding community.[6]T. S. Eliot, George Herbert (Tavistock, UK: Northcote House Publishers, 1994), 17. In 1625, Mary Ferrar purchased a dilapidated house with an abandoned chapel in the small Huntingdonshire parish of Little Gidding.[7]For an introduction to the community see A. L. Maycock, Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1980). Soon thereafter, her sons Nicholas and John joined her, along with John’s wife, Bathsheba, and their many children, as well as by her daughter, Susanna, along with her husband, John Collett, and their sixteen children. Nicholas, a one-time member of the English Parliament and ordained deacon in the Church of England, was the primary spiritual head of the community. The small community was a family affair, dedicated to unceasing prayer (as there was always someone at prayer) and following a fairly strict routine, including Sabbath observance and the recitation of the Daily Offices of the Book of Common Prayer, beginning at 4 a.m. in the summer and 5 a.m. in the winter. Outside of the community, the family engaged in the education and care of poor local children and the production of books for spiritual edification for both children and adults. Thus, Little Gidding “was a small community combining the ‘rule of a Religious house with the ordinary routine of domestic life.’”[8]Bridget Hill, “A Refuge from Men: The Idea of a Protestant Nunnery,” Past and Present 117 (1987), 110. In turn, Hill is quoting from T. T. Carter, Nicholas Ferrar: His Household and His … Continue reading In the words of Eliot, who named one of his Four Quartets (1942) “Little Gidding,” it was a place “where prayer has been valid.”[9]T. S. Eliot, “Lidding Gidding,” in T. S. Eliot: Collected Poems, 1909–1962 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1991), 201

Influenced by these men and desirous to seek the face of God, as he wrote in “The Affliction (I),” Herbert began his journey into the priesthood. His ordination in 1629 had begun a decade earlier, or so it appears. In a letter to his step-father in 1618, Herbert asked Danvers for additional money in order to buy more theological books, explaining that he was “setting foot into Divinity, to lay the platform of my future life,” claiming that he was reading “infinite Volume of Divinity.”[10]Cited in Helen Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition. Even while still a Member of Parliament in 1624, Herbert asked George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, permission to be ordained deacon, an event which appears to have occurred in late November or early December of the same year. In 1628, Herbert was released as Public Orator at the University of Cambridge; married Jane Danvers, a “loving and vertuous Lady,”[11]Citied in Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633).” Originally in Barnabas Oley, Herbert’s remains, or, sundry pieces of that sweet singer of the temple, Mr George Herbert, sometime orator of the … Continue reading we are told, the following year; and on September 19, 1630 was ordained a priest, five months after he and Jane had moved to a parish church in the village of Bemerton, near Salisbury.

Herbert as Priest

We should notice that the time between Herbert’s ordination as a deacon and his ordination as a priest is quite unusual, nearly six years. There are likely multiple reasons for the delay but Herbert’s own poem “The Priesthood” might provide the best explanation. Throughout the poem Herbert speaks of his unworthiness to serve as an effective preacher and confector of the Holy Eucharist. He concludes,

Wherefore I dare not, I, put forth my hand

To hold the Ark, although it seems to shake[12]See 2 Samuel 6:3-8 or 1 Chronicles 13:7–11.

Through th’ old sins and new doctrines of our land.

Only, since God doth often vessels make

Of lowly matter for high uses meet,

I throw me at his feet.

There will I lie, until my Maker seek

For some mean stuff thereon to show his skill:

Then is my time. The distance of the meek

Doth flatter power. Lest good come short of ill

In praising might, the poor do by submission

What pride by opposition.[13]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 152.

Herbert had a profound sense of his unfitness to be a priest. He “saw the function of a priest in a community in practical terms: primarily spiritual, of course, through teaching, preaching, charity, and the celebration of the sacraments, but extending also to the giving of legal advice and the provision of health care.”[14]Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633).” For Herbert the most essential quality for a priest was a life of holiness, which led him to write his work “A Priest to the Temple. Or the Country Parson, His Character, and Rule of Holy Life.”

In the short time that Herbert served in Bemerton he threw himself into priestly ministry, enjoying, in particular, walking twice a week to Salisbury Cathedral to join in sung Evensong and also writing poetry. Given that Herbert was often not well, it comes as little surprise to learn that his ministry at Bemerton lasted less than three years, with Herbert dying of consumption on March 1, 1633. He was only 39 years old. A decade earlier, as early as May 1622, Herbert had been contemplating his death, writing to his mother: “I always feared sickness more than death, because sickness hath made me unable to perform those Offices for which I came into the world, and must yet be kept in it.”[15]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 285. And his poem “Death” sums his thinking up well:

Death, thou wast once an uncouth hideous thing,

Nothing but bones,

The sad effect of sadder groans:

Thy mouth was open, but thou couldst not sing.

For we considered thee as at some six

Or ten years hence,

After the loss of life and sense,

Flesh being turned to dust, and bones to sticks.

We looked on this side of thee, shooting short;

Where we did find

The shells of fledge souls left behind,

Dry dust, which sheds no tears, but may extort.

But since our Saviour’s death did put some blood

Into thy face,

Thou art grown fair and full of grace,

Much in request, much sought for, as a good.

For we do now behold thee gay and glad,

As at doomsday;

When souls shall wear their new array,

And all thy bones with beauty shall be clad.

Therefore we can go die as sleep, and trust

Half that we have

Unto an honest faithful grave;

Making our pillows either down, or dust.[16]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 175-176.

Herbert as Poet

In short, this overview of Herbert’s life shows us that he was quite an intelligent man, eager to live a holy and devoted life, so much so that he submitted himself to God’s call on his life to become a priest in God’s Church. Speaking to a friend but recorded by Walton, Herbert said, “and I beseech him that my humble and charitable life may so win upon others as to bring glory to my Jesus, whom I have this day taken to be my Master and Governor; and I am so proud of his service that I will always observe, and obey, and do his will; and always call him Jesus my Master, and I will always contemn my birth, or any title or dignity that can be conferred upon me, when I shall compare them with my title of being a priest and serving at the altar of Jesus my Master.”[17]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 291. In the words of Eliot,

For the last years of his life he had been Rector of the parish of Bemerton in Wiltshire. That he was an exemplary parish priest, strict in his own observances and a loving and generous shepherd of his flock, there is ample testimony. And we should bear in mind that, at the time when Herbert lived, it was most unusual that a man of George Herbert’s social position should take orders and be content to devote himself to the spiritual and material needs of a small parish of humble folk in a rural village.[18]Eliot, George Herbert, 18.

But clearly his other God-given vocation, evidenced by his giftedness, was as a poet. As it turns out, Herbert never published any of his English poems during his lifetime and there is no evidence that he had ever shared his poetry in his lifetime except the few sonnets he sent to his mother. The poems were published posthumously by his friend Nicholas Ferrar, from two surviving manuscripts. The older manuscript contains seventy-five English poems and is already organized into three sections: “The Church-Porch,” “The Church” and “The Church Militant.” The newer manuscript contains 165 English poems.[19]Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633).” Herbert thought of his poems as “a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed betwixt God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus my Master” and only thought they should be published if Ferrar “can think it may turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul.”[20]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 311. Thankfully they were published by end of the 1633, the year of his death.

The Architecture of Herbert’s Poetry

Turning to Herbert’s poetry, I use the motif of “architecture” but with the following definition: “The special method or ‘style’ in accordance with which the details of the structure and ornamentation of a building are arranged.”[21]“architecture, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/10408. Accessed 6 July 2021. That is, we are talking about arrangement and ornamentation not the art and science of building something. This use of the term “architecture” makes sense given that the title of his largest collection of poetry is “The Temple,” which is another word for Church and, as we will see, it communicates an architectural arrangement. As Eliot reminds us,

About The Temple there are two points to be made. The first is that we cannot date the poems exactly. Some of them may be the product of careful re-writing. We cannot take them as being necessarily in chronological order: they have another order, that in which Herbert wished them to be read. The Temple is, in fact, a structure, and one which may have been worked over and elaborated, perhaps at intervals of time, before it reached its final form. We cannot judge Herbert, or savour fully his genius and his art, by any selection to be found in an anthology; we must study The Temple as a whole.[22]Eliot, George Herbert, 22.

Importantly, there is an interiority to Herbert’s architecture in that he is arranging his poetry not only by literally following the architecture of a parish church or cathedral but also by thinking of God’s architecture as touching a person’s inner journey to God. The first two stanzas of “Sion” capture this dynamic:

Lord, with what glory wast thou served of old,

When Solomon’s temple stood and flourished!

Where most things were of purest gold;

The wood was all embellished

With flowers and carvings, mystical and rare:

All showed the builders, craved the seers care.

Yet all this glory, all this pomp and state

Did not affect thee much, was not thy aim;

Something there was, that sowed debate:

Wherefore thou quitt’st thy ancient claim:

And now thy Architecture meets with sin;

For all thy frame and fabric is within.[23]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 98.

Thus, looking at Herbert’s temple as a whole we see one solid architectural edifice even only in the first few poems. Before turning to that, however, what was Herbert’s own architectural environment?

Herbert begins “The Temple” on the Church-Porch, with the first poem titled “Perirrhanterium,” which in Greek means “sprinkler” and is likely a reference to the waters of baptism. This is confirmed by the beginning of the poem “Superliminare,” which is the second and last poem in the Church-Porch section of “The Temple”: “Thou, whom the former precepts have sprinkled and taught….”[24]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 22. Regarding the beginning of “The Temple,” Carole Kessner writes, “The first section of The Temple, titled ‘The Church-porch,’ [sic] has always been something of an embarrassment to critics of Herbert’s poetry. Long, ponderous, didactic, structurally rigid, sometimes repetitious, it is altogether unlike the intimate, deeply moving, frequently charming, varied lyrics of the devotional second section, ‘The Church.’”[25]Carole Kessner, “Entering ‘the church-porch’: Herbert and wisdom poetry,” George Herbert Journal 1 (1977), 10.

Nonetheless, the point of “Perirrhanterium” is to prepare the reader to enter the Church building proper and properly, to cause one to examine herself appropriately before entering the church building. This is why it is concerned with detailing a list of sins or vices (e.g., lust, drunkenness and sloth) while also exhorting the reader to adopt a set of virtues or spiritual practices, such as living according to a rule of life, practicing asceticism and examining one’s conscience. In the poem Herbert also discusses particular ecclesial realties, such as public prayer, honesty in worship, on attending well in worship, on preaching and on the worthiness of a minister. Summing it all up, Herbert concludes,

In brief, acquit thee bravely; play the man.

Look not on pleasures as they come, but go.

Defer not the least virtue: life’s poor span

Make not an ell, by trifling in thy woe.

If thou do ill; the joy fades, not the pains:

If well; the pain doth fade, the joy remains.[26]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 21.

Simply put, it appears that Herbert is instructing the baptized Christian (hence the title of “Perirrhanterium” = sprinkler) how to live in such a way as to prepare oneself for entering the church building properly. The “Perirrhanterium” is a kind of liturgical catechism, if you will.

As mentioned above, the second and last poem of the Church-Porch section is called “Superliminare.” Its title appears to be a reference to Ex. 12:22-23 in the Latin Vulgate: “And dip a bunch of hyssop in the blood that is at the door, and sprinkle the transom [superliminare] of the door therewith, and both the door cheeks: let none of you go out of the door of his house till morning. For the Lord will pass through striking the Egyptians: and when he shall see the blood on the transom [superliminari], and on both the posts, he will pass over the door of the house, and not suffer the destroyer to come into your houses and to hurt you.” The context here concerns God’s judgment on the Egyptians by killing all of the firstborn in Egypt. God tells the Jews what to do in order to be spared, an event known subsequently as the Passover. In Christian history there is a consistent connection made between the Passover and the last and greatest Passover – the death of Jesus Christ, followed three days later by his resurrection. Of course, in the Christian tradition the resurrection is celebrated on Easter Sunday but it is also celebrated each Sunday throughout the year in as much as each Sunday is a little Easter. Thus, there is a direct connection between the Passover and Christian Sunday worship. With the poem “Superliminare” Herbert is instructing the Christian that once she has prepared herself for worship, she is to enter the church building itself through the blood of Jesus Christ. There is, metaphorically, on the transom or lintel of the church door the blood of Jesus Christ, wherein the worshipper receives forgiveness and salvation by entering into the church. In the words of Herbert, having prepared ourselves in the ways described in the “Perirrhanterium” we now “approach, and taste the church’s mystical repast.” Further,

Avoid profaneness; come not here:

Nothing but holy, pure, and clear,

Or that which groneth to be so,

May at his peril further go.[27]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 22.

Only the worthy, chosen people of God can enter the church. And this brings us to the church building proper.

“Superliminare” makes an important connection between preparation for entering the church and the primary reason for which one attends church – partaking of the Holy Eucharist: “approach, and taste the Church’s mystical repast.” “Mystical repast” is poetic-theological language for the Holy Eucharist, which explains why the first three poems in “The Church” are Eucharistic poems: “The Altar,” “The Sacrifice” and “The Thanksgiving.” “The Altar” is a shape poem (also known as a concrete poem), having the shape of a church altar. This makes sense given that the first thing you see when you walk into a church, or at least orient yourself along the center aisle, is the altar. It is important to keep in mind that in Anglican faith and practice, the Holy Eucharist is of central importance, as it is for most church traditions throughout Christian history. For Anglicans the Daily Office of Morning and Evening Prayer, which are intended to be prayed by everyone whether in community or alone, are precursors and preparatory to the regular celebration of the Holy Eucharist. In Herbert’s time the Eucharist was not celebrated every week as it often is now but it was celebrated regularly and still formed the central act of Christian worship.[28]See Bryan D. Spinks, Sacraments, Ceremonies and the Stuart Divines: Sacramental Theology and Liturgy in England and Scotland 1603-1662 (London and New York: Routledge, 2002); and Bryan D. Spinks, Do … Continue reading Remember Herbert’s own words to his friend, “I will always contemn my birth, or any title or dignity that can be conferred upon me, when I shall compare them with my title of being a Priest, and serving at the Altar of Jesus my Master.”[29]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 291. Herbert held the Holy Eucharist in greatest esteem, so much so that in The Country Parson, Herbert’s work on pastoral practice and theology, he writes the following in the chapter entitled “The Parson in Sacraments”:

The country parson being to administer the Sacraments, is at a stand with himself how or what behavior to assume for so holy things. Especially at Communion times he is in a great confusion, as being not only to receive God, but to break, and administer him. Neither finds he any issue in this, but to throw himself down at the throne of grace, saying, Lord, thou knowest what thou didst, when thou appointedst it to be done thus; therefore doe thou fulfil what thou didst appoint; for thou art not only the feast, but the way to it.[30]George Herbert, A Priest to the Temple 22; Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 232.

Thus, the highest privilege of the priest is to “break, and administer” God to the congregation. This is echoed in the fifth stanza of “The Priesthood”:

But th’ holy men of God such vessels are,

As serve him up, who all the world commands:

When God vouchsafeth to become our fare,

Their hands convey him, who conveys their hands.

O what pure things, most pure must those things be,

Who bring my God to me![31]Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 151.

Thus, Herbert’s poetical architecture begins at the altar just as one’s entrance into the church building begins with the altar, at least visually.

“The Altar” is followed by “The Sacrifice.” In his book Eucharistic Sacrifice, former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams rightfully notes that the classical Reformation objection to the use of sacrificial language in Eucharistic theology compromises the “once for all” nature of Christ’s sacrifice as attested in Heb. 10:10: “we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all.” Similarly, we must note too Heb. 9:11-12: “But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come… he entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption.” Moreover, especially in the thought of reformer John Calvin (d. 1564), there is the issue that if the Holy Eucharist is a sacrifice then there needs to be an agent who performs the sacrifice suggesting that Christ is not able to save us by and through his accomplished work on the cross.[32]John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion 4.18.13. See also Joseph N. Tylenda, “A Eucharistic Sacrifice in Calvin’s Theology?,” Theological Studies 37.3 (1976): 456-466. Finally, there is also the issue that if there needs to be an agent then that agent is the priest, transferring sacrificial agency from Christ to the Church, making way for a misunderstanding of the nature of the Christian priesthood – a so-called “clericalism.” In short, the language of Eucharistic sacrifice is not always welcome in the Protestant churches.

Nonetheless, in the 1559 Book of Common Prayer, the one used by Herbert, the priest, in the Eucharistic liturgy, says, “Almighty God… our heavenly father whiche of thy tender mercye, diddest give thine onely Sonne Jesus Christ, to suffer death upon the Crosse for our redemption, who made ther (by his one oblation of himself once offered) a ful, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the synnes of the whole worlde”; and, “O Lorde and heavenly father, we thy humble servaunts, entierly desire thy fatherly goodnes mercifully to accept this our Sacrifice of praise and thankesgeving.” Thus, it seems that the Anglican liturgy thinks in terms of sacrifice. In the words of the Anglican priest William Bedell from 1624: “[If by Eucharistic sacrifice you mean] a memory and representation of the true Sacrifice and holy immolation made on the altar of the cross… we do offer the sacrifice for the quick and the dead, by which all their sins are meritoriously expiated, and desiring that by the same, we and all the Church may obtain remission of sins, and all other benefits of Christ’s Passion.”[33]Gilbert Burnet, The Life of William Bedell, D.D., Bishop of Kilmore in Ireland (Dublin: M. Rhames, 1736), 405.

As well, Article 31 of the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion says, “The offering of Christ once made is the perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction for all the sins of the whole world, both original and actual, and there is none other satisfaction for sin but that alone. Wherefore the sacrifices of Masses, in which it was commonly said that the priests did offer Christ for the quick and the dead to have remission of pain or guilt, were blasphemous fables and dangerous deceits.” It seems then that Article 31 forbids Anglicans from holding to any theology of Eucharistic sacrifice, which are “blasphemous fables and dangers deceits.”

Yet we must notice the double plural: “sacrifices of Masses.” Anglican Eucharistic theology, which Herbert followed, does not reject a theology of sacrifice wholesale, though it does reject a theology of sacrifice that is divorced from Jesus Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice. As Jeremy Taylor (d. 1667), Anglican bishop and theologian, wrote in the mid-seventeenth century, “For as it is a commemoration and representment of Christ’s death, so it is a commemorative sacrifice; as we receive the symbols and the mystery, so it is a sacrament. In both capacities the benefit is next to infinite.”[34]Jeremy Taylor, The Great Exemplar of Sanctity and Holy Life according to the Christian Tradition (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans et al., 1847), 642. According to the Book of Common Prayer, the worshipper “continue[s], a perpetual memory of that his precious deathe, untyll his comminge againe.” An Anglican Eucharist is a “perpetual memory” of Jesus’ one-for-all sacrifice for he “made ther (by his one oblation of himself once offered) a ful, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the synnes of the whole worlde.” In Anglican faith and practice the priest is not re-sacrificing Christ, he is participating, memorializing Christ’s all-sufficient sacrifice on Calvary. Thus, it is appropriate that after “The Altar” there would be a poem on sacrifice in order to emphasize that which Christ accomplished once and for all on the Cross of Calvary but also the sacrifice that occurs at each Holy Eucharist. Herbert’s architecture continues to take shape.

Conclusion

Let us conclude with a comment about the third poem in the Church section – “The Thanksgiving.” The liturgy of the Holy Eucharist used by Herbert ends with this prayer: “Almighty and everlastinge God, we moste hartely thancke the, for that thou doest vouchsafe to fede us, whiche have duly received these holy misteries, with the spiritual fode of the moste precious body and bloude of thy sonne, our saviour Jesus Christ.” That is, the Eucharistic liturgy ends with a thanksgiving to God for what he has done for each believer and this becomes obvious when we consider that the Eucharist (εὐχαριστέω) is literally a giving of thanks to God. Thus, it would seem appropriate for Herbert to include a poem of thanksgiving after a poem on the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. It follows then that the architecture of Herbert’s poetry shadows the literal architecture of the church building, beginning on the church-porch with proper preparation for worship, and then, upon entering the church, with the altar on which is offered the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, for which worshippers give thanksgiving. Again, space prohibits us from going further but the architecture of “The Temple” continues moving from the literal architecture of a church building to the interior architectural elements of our very spiritual life, such as mortification and prayer. And this makes sense given that Christian believers, according to the Apostle Paul, are temples of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 6:19). And such language is not unknown in Anglicanism. As Scottish Bishop George Innes (d. 1781) wrote in his catechism, “In our water-baptism the Holy Ghost purifies us and fits us to be a Temple for himself.”[35]George Innes, A catechism, or, The principles of the Christian religion: explained in a familiar and easy manner, adapted to the lowest capacities (Edinburgh; reprint New Haven: T. & S. Green, … Continue reading In this way, all worshippers are Herbert’s Temple.

References

| ↑1 | John Tobin, ed., George Herbert: The Complete English Poems (London: Penguin Books, 1991), 271. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A. J. Smith, ed., John Donne: The Complete English Poems (London: Penguin Books, 1971), 105. |

| ↑3 | On choirs at Westminster Abbey in general see Edward Pine, The Westminster Abbey Singers (London: Dennis Dobson, 1953). |

| ↑4 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 270. |

| ↑5 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 41. |

| ↑6 | T. S. Eliot, George Herbert (Tavistock, UK: Northcote House Publishers, 1994), 17. |

| ↑7 | For an introduction to the community see A. L. Maycock, Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1980). |

| ↑8 | Bridget Hill, “A Refuge from Men: The Idea of a Protestant Nunnery,” Past and Present 117 (1987), 110. In turn, Hill is quoting from T. T. Carter, Nicholas Ferrar: His Household and His Friends (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1893), 97. |

| ↑9 | T. S. Eliot, “Lidding Gidding,” in T. S. Eliot: Collected Poems, 1909–1962 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1991), 201 |

| ↑10 | Cited in Helen Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition. |

| ↑11 | Citied in Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633).” Originally in Barnabas Oley, Herbert’s remains, or, sundry pieces of that sweet singer of the temple, Mr George Herbert, sometime orator of the University of Cambridg. [sic]: Now exposed to publick light (London: Timothy Garthwait, 1652), n. p. |

| ↑12 | See 2 Samuel 6:3-8 or 1 Chronicles 13:7–11. |

| ↑13 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 152. |

| ↑14, ↑19 | Wilcox, “George Herbert (1593-1633).” |

| ↑15 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 285. |

| ↑16 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 175-176. |

| ↑17, ↑29 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 291. |

| ↑18 | Eliot, George Herbert, 18. |

| ↑20 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 311. |

| ↑21 | “architecture, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2021, www.oed.com/view/Entry/10408. Accessed 6 July 2021. |

| ↑22 | Eliot, George Herbert, 22. |

| ↑23 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 98. |

| ↑24, ↑27 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 22. |

| ↑25 | Carole Kessner, “Entering ‘the church-porch’: Herbert and wisdom poetry,” George Herbert Journal 1 (1977), 10. |

| ↑26 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 21. |

| ↑28 | See Bryan D. Spinks, Sacraments, Ceremonies and the Stuart Divines: Sacramental Theology and Liturgy in England and Scotland 1603-1662 (London and New York: Routledge, 2002); and Bryan D. Spinks, Do this in Remembrance of Me: The Eucharist from the Early Church to the Present Day (London: SCM Press, 2013). |

| ↑30 | George Herbert, A Priest to the Temple 22; Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 232. |

| ↑31 | Tobin, ed., George Herbert, 151. |

| ↑32 | John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion 4.18.13. See also Joseph N. Tylenda, “A Eucharistic Sacrifice in Calvin’s Theology?,” Theological Studies 37.3 (1976): 456-466. |

| ↑33 | Gilbert Burnet, The Life of William Bedell, D.D., Bishop of Kilmore in Ireland (Dublin: M. Rhames, 1736), 405. |

| ↑34 | Jeremy Taylor, The Great Exemplar of Sanctity and Holy Life according to the Christian Tradition (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans et al., 1847), 642. |

| ↑35 | George Innes, A catechism, or, The principles of the Christian religion: explained in a familiar and easy manner, adapted to the lowest capacities (Edinburgh; reprint New Haven: T. & S. Green, 1791), 9. |