The baptism of Christ is among the earliest New Testament scenes selected for depiction in Christian art. Günter Ristow mentions this in Die Taufe Christi (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1965, 12). It is found in the catacombs, on early christian sarcophagi, and in the very first christian monumental architecture. Given all the water imagery in the elaborate iconographic program in the baptistery of the house church at Dura Europa (dating to around 230), it seems likely that an image of the baptism of Christ must have been present somewhere on one of the walls that have not survived. This is only speculation, though. The catacomb paintings of the subject have survived almost as mere pictograms: a baptizer, a baptizee, and a dove can be discerned, but little detail.

The baptism of Christ is among the earliest New Testament scenes selected for depiction in Christian art. Günter Ristow mentions this in Die Taufe Christi (Recklinghausen: Verlag Aurel Bongers, 1965, 12). It is found in the catacombs, on early christian sarcophagi, and in the very first christian monumental architecture. Given all the water imagery in the elaborate iconographic program in the baptistery of the house church at Dura Europa (dating to around 230), it seems likely that an image of the baptism of Christ must have been present somewhere on one of the walls that have not survived. This is only speculation, though. The catacomb paintings of the subject have survived almost as mere pictograms: a baptizer, a baptizee, and a dove can be discerned, but little detail.

Roland Bainton gives us the key to interpreting the smudgy image in Behold the Christ (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1974, 78). It is the baptism of Christ rather than merely the baptism of a believer. The presence of the conspicuously large dove, signifying the Holy Spirit’s descent on Jesus, illuminates the matter. In most of these earliest images, the dove approaches Jesus obliquely, flying toward him at a vector which later artists would usually reject in favor of a strict vertical configuration.

It is interesting to note that the earliest representations of the baptism of Christ occur in settings which imply a connection with death: in the catacombs and on christian sarcophagi. The early christians interpreted their baptism as a participation in the death of Christ (following Romans 6:3ff), and understood their participation in this redeeming death to be also the promise that they would share in Christ’s victory over death, the resurrection. Thus the image of Christ’s baptism found its place alongside other images which called to mind divine deliverance: Daniel in the lion’s den, Susannah vindicated from the elders, the three Hebrew youths in the fiery furnace, and of course Jonah emerging from the belly of the whale.

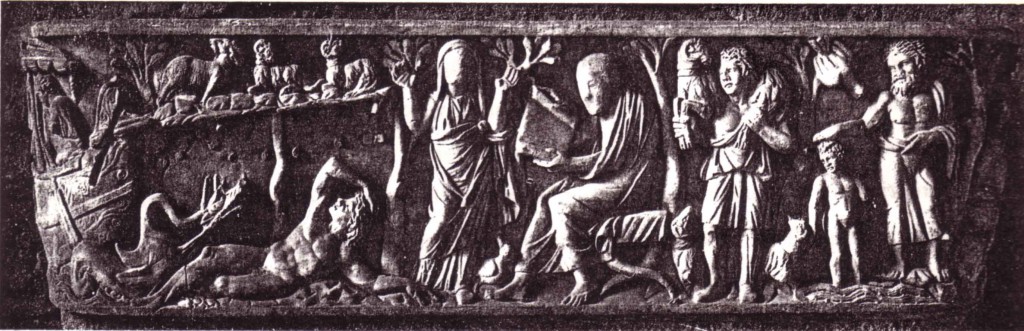

The most celebrated sarcophagus bearing the image of Christ’s baptism dates from around 270 and can be found in Santa Maria Antigua, Rome. The baptism is here presented alongside the images of Jonah, a faceless orant figure, a seated prophet, and a depiction of Christ as the Good Shepherd. The Jordan is represented by a few wavy lines which barely cover Christ’s feet, and the landscape is indicated only by two trees which also serve to separate this image from others surrounding it on either side. With all extraneous detail stripped away, all that remains are the three essential characters: Jesus, John the Baptist, and the dove signifying the Holy Spirit. Their relative sizes are the most striking elements of the composition: John is by far the largest, stretching from top to bottom of the image zone, standing on a rock and dressed in loose, draping garments. He extends his right hand, which rests on the head of Christ. John said of Jesus: “He must increase, but I must decrease” (John 3:30). Those words are certainly appropriate for this monumental baptizer. Christ, curly-headed and beardless, is only about two-thirds the size of John. The diminutive stature of Christ is probably best explained by the convention which understood baptism as a new birth, and therefore recognized that anyone undergoing baptism should be represented as a new person, or literally a child.

Christ stands with his weight on one leg, turning his head away from John. His right hand (his left arm is damaged, broken off above the elbow) rests beside him, actually coming into contact with a sheep whose head has strayed across the boundary from the neighboring Good Shepherd image. We might say that for those who have eyes to see, this boyish Christ is revealing himself as not merely the recipient of John’s baptism, but as the one who alone baptizes with the Holy Spirit. The dove in this image is the smallest of the three figures, but is nevertheless remarkably large, about the size of Christ’s entire torso and head. Entering the frame at a forty-five degree angle, the dove contrasts energetically with the two human figures who deviate only slightly from the vertical.

The three figures fill their rectangular frame completely, and constitute a strong visual threesome. The question arises: is this a reference to the Trinity? Of course John the Baptist is not a member of the divine Triad, but is it possible that this large bearded figure is to be read as a cipher for God the Father? Three factors argue in favor of this reading: First, the baptism of Christ has long been regarded, above all in the eastern church, as the epiphany of the Trinity; this has been one of its central meanings throughout the Christian tradition. Was it conceived this way as early as 270, and did this conception find a visual expression here? Secondly, the so-called Dogmatic Sarcophagus, dating from roughly the same period as this sarcophagus, includes an image of three human figures creating Adam and Eve. This indicates that the notion of God as Trinity, even at this early date, could be represented by the presence of three figures. Finally, the writings of the church father Irenaeus of Lyons (ca. 120-202) contain a trinitarian exegesis of the name “Christ” which fits well in this baptismal context:

For in the name of Christ is implied, He that anoints, He that is anointed, and the unction itself with which He is anointed. And it is the Father who anoints, but the Son who is anointed by the Spirit, who is the unction, as the Word declares by Isaiah, ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because He hath anointed me,’ pointing out both the anointing Father, the anointed Son, and the unction, which is the Spirit (Irenaeus, Against Heresies III:18,3).

Do we have on this sarcophagus a visual allusion to “the anointing Father, the anointed Son, and the unction, which is the Spirit?” We cannot say for certain. Chief among the arguments against this interpretation is the fact that John the Baptist makes a difficult cipher for God the Father. Could early Christians read “through” John to the anointing Father? Would John’s bearded, toga-clad resemblance to Zeus help or hinder the viewer in seeing him as a cipher for God the Father? If there is a Trinity reference here, then this would be by far the earliest “bearded old man” representation of God in Christian history. The evidence is inconclusive.

These earliest images exhibit the basic structure of the icon of Christ’s baptism: Jesus being baptized by John, with the Holy Spirit’s emblematic dove descending from heaven. Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, provides several more examples of the image which retain this original simplicity (in Vol. I, pp. 127-145 and accompanying plates). Schiller provides one example of even more compressed representation: a sarcophagus from San Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, dating to 460-470, on which is shown the dove descending vertically on a cross in a basin.

These earliest images exhibit the basic structure of the icon of Christ’s baptism: Jesus being baptized by John, with the Holy Spirit’s emblematic dove descending from heaven. Gertrude Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, provides several more examples of the image which retain this original simplicity (in Vol. I, pp. 127-145 and accompanying plates). Schiller provides one example of even more compressed representation: a sarcophagus from San Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, dating to 460-470, on which is shown the dove descending vertically on a cross in a basin.

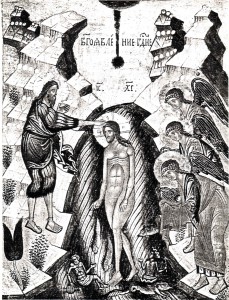

Details and elaborations accumulate rapidly, and by the sixth or seventh century all the major elements of the iconography have appeared. An examples of this is the sixth or seventh-century Palestinian image provided by Schiller in plate 357, which already includes two angels holding robes, the Jordan heaped up between its banks, two onlookers, and the hand of God.

In the next several posts in this series, I will work through the various parts of the iconography, illustrating significant developments within each topic. The order will be as follows: John, the Jordan River, Angels, onlookers, the representation of light, and finally the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The progression from the earliest examples of the image through its classic elaboration and development in the middle Byzantine period should be easy to discern from the various examples given. Our focus will be on this “classic icon” structure, which exhibits such obvious continuity in its main features, including the basic symmetrical composition.

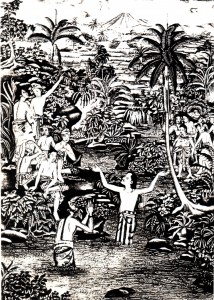

From at least the fifth century (Ravenna’s baptisteries) its conventions are clearly visible; they are definitively expressed in the eleventh century (the “big three” Middle Byzantine structures: Nea Moni, Moni Daphni, and Hosios Loukas); and continue to this day in the innumerable panel icons which have their place in the festal cycle of the Eastern churches. With this image-type as a sort of visual canon, we will also freely examine independent interpretations of the baptism which emerged in the West following the Renaissance, as well as a few examples of East Asian and Latin American inculturations of the iconography (for instance, this one from Bali).