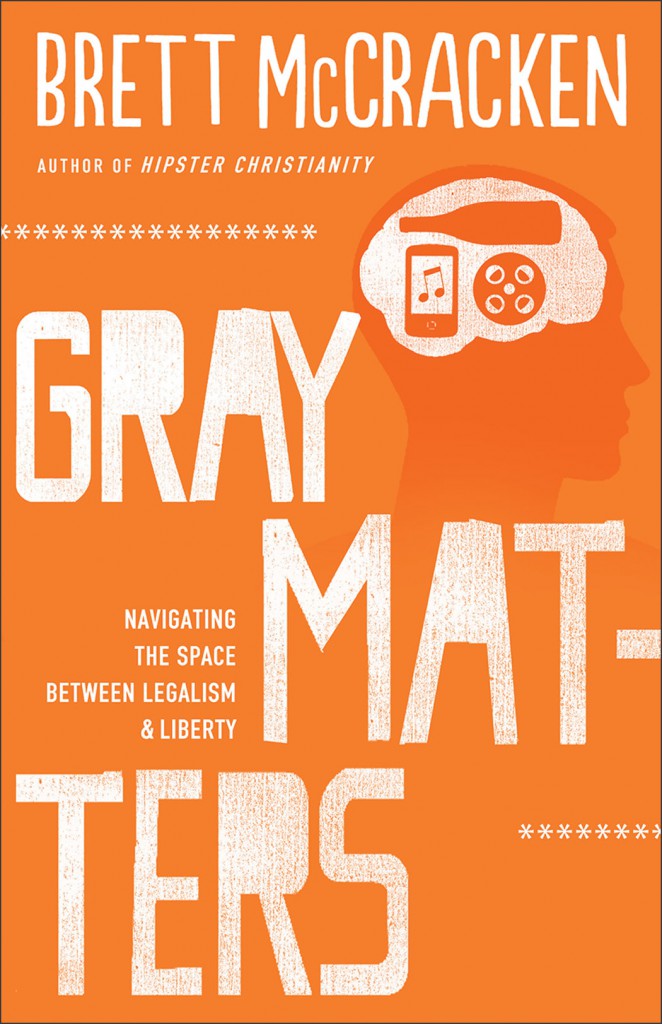

Brett McCracken’s new book Gray Matters: Navigating the Space Between Legalism & Liberty is a vade mecum for cultured Christians. It’s for Christians who are either up to date enough that they’d never say vade mecum, or who are way past up to date and are trying to bring vade mecum back.

Brett McCracken’s new book Gray Matters: Navigating the Space Between Legalism & Liberty is a vade mecum for cultured Christians. It’s for Christians who are either up to date enough that they’d never say vade mecum, or who are way past up to date and are trying to bring vade mecum back.

A vade mecum is a handbook (literally a “go with me”) that a wayfarer would want to have along on a journey, and Christians are certainly on a journey through culture in these strange days. McCracken (author of the timely and well-received Hipster Christianity) has written a thoughtful book, one that will provide direction, bring clarity, and prompt deep reflection. But none of those words quite capture the way Gray Matters is designed to be put into immediate use.

Gray Matters is a how-to book, though a particularly cerebral one (as the neurological pun in the title suggests). It gives the reader a proper orientation for how to be a consumer. That is not a fashionable way to put things, because at least since Andy Crouch’s important 2008 book evangelicals have been exhorted to get past the baby steps of culture-consuming and culture-critiquing, to the responsible and constructive business of Culture Making. And as McCracken admits, “consumer is a very ugly word when we think of it in the Vegas sense, but there are other ways to think about it. One can consume in a manner that is passionate yet dignified, sensuous yet controlled, thoughtful yet not academic.”

So “one of this book’s aims is to rehabilitate the term consumption,” rescuing it from the connotation of “something indulgent, reckless, and altogether unseemly.” A short sidebar on page 17 lists eight “ways we cheapen consumption, and a few pages later in the introductory chapter McCracken lays out seven themes that he will develop throughout the book:

1. Partaking in culture is part of our mission.

2. Mature consumption requires wise stewardship of our resources.

3. Community plays a vital role in partaking of culture.

4. Enjoying God’s good creation is an act of worship.

5. It is good to cultivate and refine our taste.

6. We need to be trained in discernment, the ability to assess critically.

7. Healthy enjoyment requires moderation.

The bulk of the book is made up of discussions of food, pop music, movies, and alcohol, which McCracken says are “four areas of pop culture that we don’t often think about as necessarily theological.” But if you’ve ever been in or worked with a youth group, you know that these are four of the main topics that draw young people into spirited theological debate. In the four major sections of the book, McCracken takes that youth group discourse and situates it in a much broader context. It looks to me like the decisions being made by fourteen-year-olds about what to listen to and what to eat really do map onto significant struggles faced by evangelical twenty-somethings today, and increasingly by thirty-somethings and beyond. I don’t know how young of an audience could handle McCracken’s book: it seems to me it would take an extraordinarily thoughtful and sensitive high school student to profit from it. But perhaps you know one. And if I were still involved in youth or college ministry, I would be leaving copies of this book laying around on every horizontal surface in my office, to be perused by students, parents, pastors, and ordinary church members.

One of the things that will commend Gray Matters to a sophisticated audience is the way McCracken dares to mine his own experiences as a consumer, critic, and appreciator of the range of cultural goods. After talking about the ways we go wrong and right with food, he provides a three-page list of his own peak moments as an eater. It’s a nice touch: instead of being self-indulgent or exhibitionist, it’s an evocative way of prompting the reader to consider, “what should be on my own timeline of food memories?” Personally, I realized that it would be a slow and difficult task for me to come up with three pages as thoughtful as McCracken’s. The reason? I’m probably guilty of ingratitude and unreflectiveness in my gustatory life.

McCracken includes similar interludes on the subject of music and movies, and the specificity of his lists of favorite bands and movies will be a good hook to help readers engage. He is especially in his element discussing film, and draws on his experience as a movie reviewer for Christianity Today, even including some reflections on the feedback his published reviews have received. I especially appreciated the concreteness and vulnerability with which he described his opinions about two movies that fall just above and just below the line of what he’ll expose himself to as a Christian consumer of film. The two movies are both edgy, and he’s not willing to recommend either of them for others: the recent Shame and the older Salò. His description of why one falls just within his acceptable range and the other just beyond it carries the perfect ring of honesty. He can barely decide about these movies, but he has to. Good consumers will face this situation over and over.

But for all the up-to-date film and music references, what I appreciate most about Gray Matters is what strikes me as the old-fashioned wisdom that pervades it. In particular, McCracken is excited to teach people the crucial skill of negotiating the middle path between the opposite errors of legalism and license. I grew up with a good grasp of these two errors, and at least in my memory ordinary Christians talked about them in exactly those terms. They are not categories I hear very much of these days, and I sometimes think that’s because so many young Christians have settled into one camp or the other. McCracken bids fair to revive the categories and teach thoughtful Christians how to use them. He writes crisply and engagingly on them; even the animated trailer for the book gets the basic idea across in a few seconds. You can learn this stuff from the Puritans, I suppose, but it sure is nice to have it in contemporary idiom.

One final remark. I like to situate Christian books like this in their proper place within the categories of systematic theology. A lot of Christian books are too unfocused to locate in this manner, but McCracken’s is clear. This is fundamentally an entry in the Christian doctrine of creation, and particularly in the interface between humanity and the rest of God’s good world. Because of its practical nature and the weather eye it keeps on the church’s mission, it could also fit into the category of discipleship. But as a handbook for becoming consummate consumers, Gray Matters fills out some neglected chapters in the doctrine of created goods.