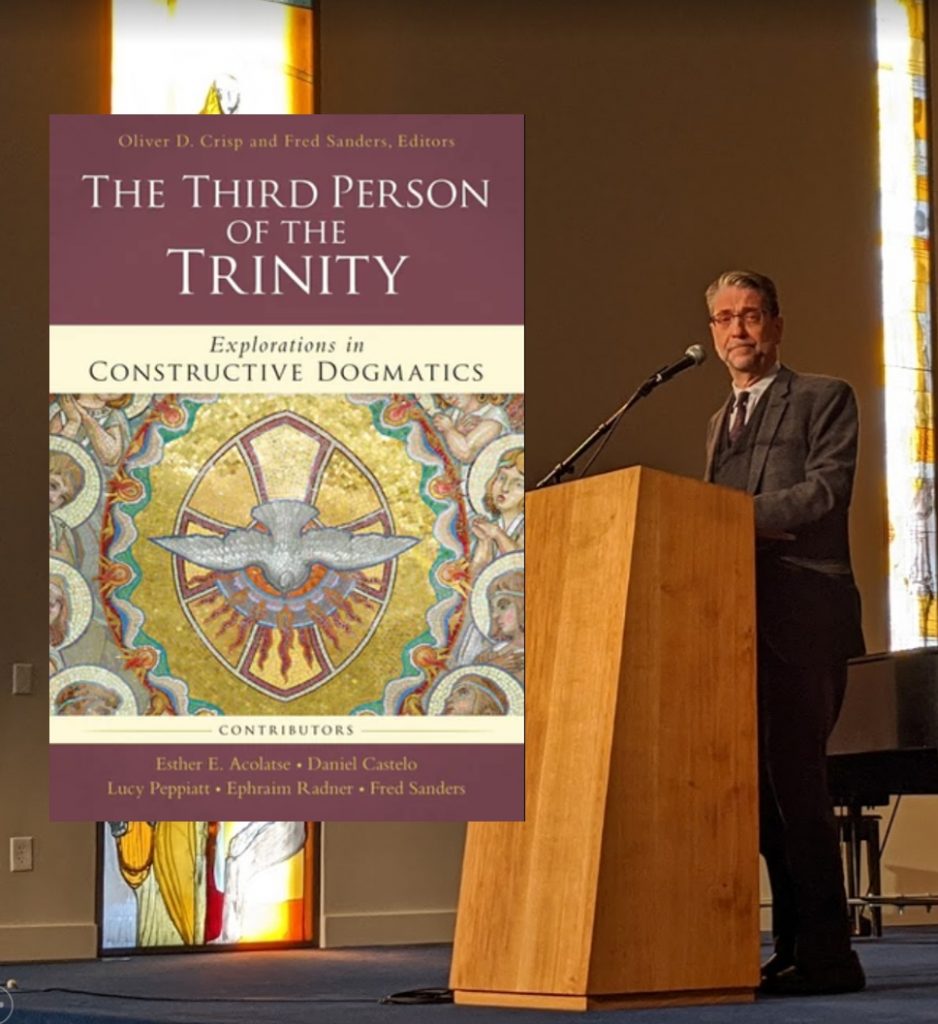

Dr. Ephraim Radner delivered a memorable paper at the 2020 Los Angeles Theology Conference last January. Those of us in the audience were struck by the depth and honesty of what he shared that day about how the modern world has come to think about the Holy Spirit. Fortunately, his paper has now been published as a chapter in the conference volume, The Third Person of the Trinity (Zondervan 2020).

Your chapter in The Third Person of the Trinity is entitled “Running Away from Sorrow: Pneumatology and Some Modern Discontents.” What is it about?

Religion may not be the opium of the people (it clearly isn’t), but it is, as the phrase goes, a good “coping mechanism”. And why shouldn’t it be? The Christian faith brings with it encouragement, hope, peace, especially in the face of great difficulties, and it does this because of the God in whom that faith rests. But coping can go too far, and become a consuming form of avoiding the very things that God gives us as the gift of our life, including just the difficulties that challenge us. When that happens, we fall into the great pit of “distraction” that Pascal warns of. Modern pneumatology, as I have followed its rise and application, has often become the apotheosis of Distraction writ large – the insistence that the Christian faith gets us “out of the world” or beyond it or at least beyond its intractable givenness.

My essay, “Running Away From Sorrow: Pneumatology and Some Modern Discontents” takes as its focus the single claim that “the Holy Spirit teaches us to die faithfully”. Not “helps us to die faithfully” (which the Spirit also may do, of course), but “teaches”, that is, leads us to face with faith the fact that we are born and then die, joined to Christ. The point of this claim is to wrench our understanding of the Holy Spirit back from the great distraction of coping with life to the facing into and embrace of what life actually is, a divine gift of unimaginable and uncontrollable contours, edges, shades, and energies within which the depths of God’s deep secrets are shared, as in the flesh of Jesus.

A large portion of the essay is devoted to reflecting on the life and theological interests of a little-known 20th century theologian, Ulrich Simon, a Jewish Christian who lost much of his family to the ravages of WW II but himself escaped to Britain. Simon’s vocation, I suggest, is an example of struggling with the claim laid out above. Simon was one of the first Christian theologians to write about the Holocaust’s religious meaning. And even though he does not write a lot about the Holy Spirit itself, his enveloping interest, for instance, in the concept of tragedy and its relation to the Gospel offers a window onto a profound alternative to modern pneumatology’s captivation by distraction. My brief reflection on Simon’s life and work then leads me to make some broader conclusions about how Christian consideration of the Holy Spirit can be pursued in a more honest way in our era.

How does this chapter fit into your teaching or your writing?

Those familiar with a recent book of mine, A Profound Ignorance: Modern Pneumatology and Its Anti-Modern Redemption, will recognize my essay here as a but a small refashioning, within the compass of a particular story, of some of the main themes of that volume. For a number of years I have been teaching on the rise of pneumatology as a modern theological discipline, as well as on the rise of the project of “theodicy” in early modern Christian thought. Without originally assuming these two topics’ connection, it eventually became clear to me that they are in fact twin cultural-theological developments, dependent on and expressive of a common set of experiential pressures in the modern West. My book was the fruit of this thinking, and the essay here but a modest application of its thesis.

Where did the idea for this particular essay come from?

The essay itself was spurred, less immediately by my larger writing project, than by my discovery of Ulrich Simon’s work. While reading here and there for another project involving Anglican Jewish Christians, I came across Simon and delved into his own intellectual autobiography. This immediately seemed to cast light on my own reflections about pneumatology itself. Jewish Christians (among whom I would include some Messianic Jews as well) are, in our day, in an odd location, one that I wonder might in fact embody just some of the necessary (i.e. divine) challenges to the religion of distraction that much of the Gentile church has given itself over to in the past few centuries. That’s another topic.

What’s the next thing you’re working on, or looking forward to working on?

I am pondering a book on Christian politics. Much of my writing before the past few years has been devoted to ecclesiology, and I will be returning to this area again. But now informed by some of this pneumatology/theodicy material. In a world caught up in the great currents of distraction – that is, the pull away from the givens of our existence – how does the Christian church engage a common civil life in way that helps keep us all steadily where we have been placed, that is, in a mortal life lived before God?

A bonus question not related to this book chapter: What’s the most stimulating thing you’ve read lately in theology?

Given my interests of the moment, I find biography more interesting than theoretical disquisitions – to pick up the theme of the essay in this volume, who has learned how to die faithfully? And thus, who has in fact been “taught by the Holy Spirit”? There is the entire genre of the “life of a saint”, or that of the missionary narrative, with much to offer. But there are also simply the stories of women and men who deal with their fundamental pneumatic vocation somehow, and by doing so, whether consciously or unconsciously, reveal something of the God who made them and leads them. To move to a more novelistic reflection on such themes, I have been challenged by re-reading Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, a deeply religious, and wonderfully honest, book on many levels.

For more sneak-peeks of The Third Person of the Trinity, check out our other interviews. You can pick up a copy of the book here.