Henry Barclay Swete (March 14, 1835 -1917) was an Anglican theologian whose long career took place during the decades when the waters of destructive liberal criticism were rising all around traditional Christianity, and seemed to be coming in right up to the soul of the church. Liberalism was advancing, and the epochal reactions against it would only take place at the very end of Swete’s life, or shortly after: the anti-modernist oath of Pius X, the international network of the brainy fundamentalists behind The Fundamentals, the sustained protest of Karl Barth. And by the time the reactions set in, they were necessarily reactionary.

Henry Barclay Swete (March 14, 1835 -1917) was an Anglican theologian whose long career took place during the decades when the waters of destructive liberal criticism were rising all around traditional Christianity, and seemed to be coming in right up to the soul of the church. Liberalism was advancing, and the epochal reactions against it would only take place at the very end of Swete’s life, or shortly after: the anti-modernist oath of Pius X, the international network of the brainy fundamentalists behind The Fundamentals, the sustained protest of Karl Barth. And by the time the reactions set in, they were necessarily reactionary.

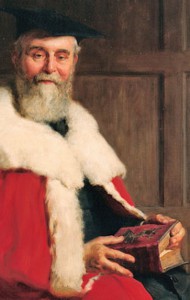

During those dark decades of the late nineteenth century, H. B. Swete, professor of divinity at Cambridge and at Kings College, London, consistently fought the good fight on more fronts than one scholar could reasonably be expected to.

The Church Times, in a 1917 obituary, noted how scholars of his generation felt toward Swete: “We were perplexed by Harnack, alarmed by Schmiedel, in danger of being carried away by Tyrrell, distressed by Schweitzer, but always we knew that there was a ripe scholar, preserving at the time a profound devotion to the Catholic Faith and an open and liberal mind, who would bring out of his treasures things new and old and unfold to us ‘sound learning and religious education.'” (Note well: there has been some semantic drift since 1917: What they mean by “Catholic” and “liberal” is “universal” and “generous,” which does not detract from the fact that Swete was conservative and Protestant. See, he was a liberal, Catholic, conservative, Protestant… see why you can’t talk like that?)

How many fronts was Swete active on? It’s difficult to count (browse them with this search at Google books). He published an edition of the Greek Old Testament and of Theodore of Mopsuestia’s Commentary on Paul’s Epistles. He wrote a history of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. He wrote commentaries on Mark and Revelation. He wrote accessible books on the Apostle’s Creed, studies of liturgical handbooks, studies of English service-books from before the Reformation, a short, popular introduction to the study of the church fathers, and several sermonic books on doctrinal topics like the farewell discourses of Christ from the gospel of John, the post-resurrection appearances of Christ, the ascension of Christ, and eternal life.

Nobody writes in that many fields, especially not fields that require advanced technical knowledge. Part of the explanation is simply that he loved to study, and was a natural polymath. But another reason for his wide range of studies is that he understood the times: the most damaging modernist attacks on traditional Christianity demanded a response from somebody who could argue credibly in all of these fields.

Swete was motivated in his vast work by a deep Christian faith and a desire to serve with faithful scholarship that would equip pastors and parishioners to stand their ground intellectually. The author of an obituary said of him:

Under German influence the word Theologian has come to mean for us a person who interests himself in studies that bear upon religion in some direction, without necessary reference to the religious convictions or the contents of belief of the student. Not in that sense was Dr. Swete a theologian. He was a theologian in the older sense of one who has heard the charge: “Hold thou the truth; define it well.”