I sometimes promote myself as the “world’s greatest systematic theologian cartoonist,” because it’s a pretty safe boast. If I ever meet another professional theologian who’s also a published cartoonist, I’ll have to adjust my bragging to something like “one of the two greatest.” But while I might be the only theology prof to publish cartoons, I’m certainly not the only cartoonist to do Christian comic books. There is in fact about a century of interesting work in this field. Here are the five most important.

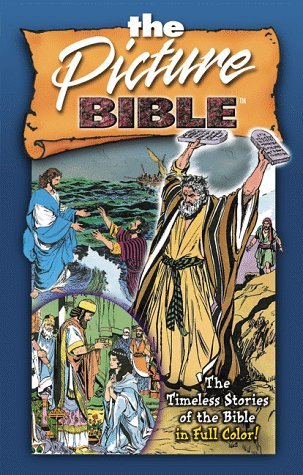

The Picture Bible: The best of the comic book Bibles so far: the whole Bible, rendered in comic book form with remarkable consistency over 750 pages. Written by Mrs. Iva Hoth, drawn by Andre LeBlanc, and published serially in the David C. Cook Sunday School Curriculum in the 1950s, this thing is still in print and widely available.

The Picture Bible: The best of the comic book Bibles so far: the whole Bible, rendered in comic book form with remarkable consistency over 750 pages. Written by Mrs. Iva Hoth, drawn by Andre LeBlanc, and published serially in the David C. Cook Sunday School Curriculum in the 1950s, this thing is still in print and widely available.

I grew up with this comic book Bible in a six-paperback set that nestled into their own little box. LeBlanc’s drawings are not flashy, but they are exquisite: he can draw anything, he frames scenes well, varies the thickness of his lines, and leaves plenty of open space while finding logical places for heavy black spaces on each page. I don’t know how Hoth and LeBlanc collaborated on this, but they worked out an elegant dance between word and image, taking turns letting each other get the main point across as the story demanded it.

The colorized editions available these days tend to distract the eye from LeBlanc’s power as an illustrator, but the color is pretty well done, and surely boosts the popularity of the book.

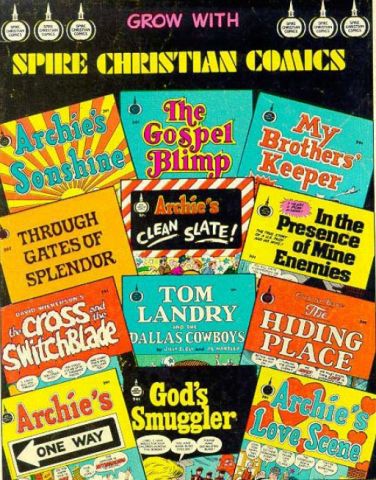

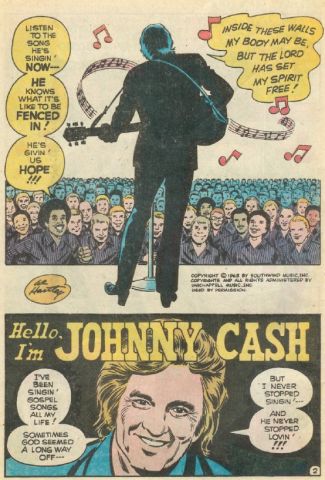

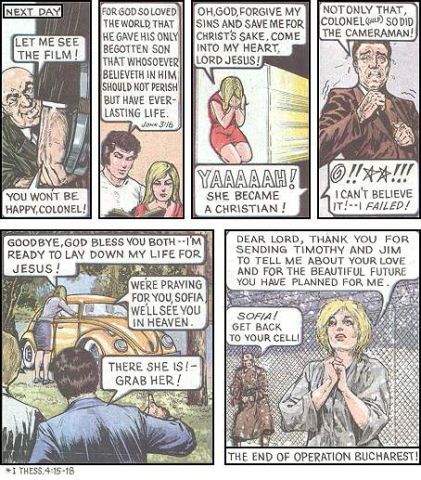

Spire Christian Comics. Nearly five dozen full-length comic books by Al Hartley on a range of topics, published in the 1970s by Fleming Revell and Barbour. They include comic book versions of books like Brother Andrew’s God’s Smuggler, Elisabeth Eliot’s Through Gates of Splendor, Corrie Ten Boom’s The Hiding Place, and David Wilkerson’s The Cross and the Switchblade, plus the life stories of Tom Skinner, Chuck Colson, Johnny Cash, Tom Landry, and more. See a completist’s list here. Al Hartley was also responsible for the strange and wonderful career of Archie as an evangelical Christian, witnessing to the gang at Riverdale High School in nineteen comic books.

Spire Christian Comics. Nearly five dozen full-length comic books by Al Hartley on a range of topics, published in the 1970s by Fleming Revell and Barbour. They include comic book versions of books like Brother Andrew’s God’s Smuggler, Elisabeth Eliot’s Through Gates of Splendor, Corrie Ten Boom’s The Hiding Place, and David Wilkerson’s The Cross and the Switchblade, plus the life stories of Tom Skinner, Chuck Colson, Johnny Cash, Tom Landry, and more. See a completist’s list here. Al Hartley was also responsible for the strange and wonderful career of Archie as an evangelical Christian, witnessing to the gang at Riverdale High School in nineteen comic books.

Hartley’s Spire series is definitely marked by its decade of origin: It’s so seventies that you need a good sense of ironic distance to appreciate this work fully. Also, as an Archie artist, Hartley has a kid-friendly style that skews all of this work toward a younger audience: the eyes are big, the word balloons are clear and short. This works one way when he’s doing Barney Bear or Archie, but when he takes on adult subject matter, as he frequently does (drugs, sex, gangs, prison, torture, concentration camps), it can make an odd contrast of form and content. But these Spire comics were a daring cartoon undertaking, and Hartley was inventing new symbols and conventions at a furious pace. He had a great sense of the temper of the times, and there’s something uncanny in how perfectly his comic book adaptations fit with those 1970s Christian paperback bestsellers. The hundreds of pages he cranked out are a legacy of visual communication.

These things are not in print! But their sales have been estimated into the tens of millions, so they’re not impossible to find used.

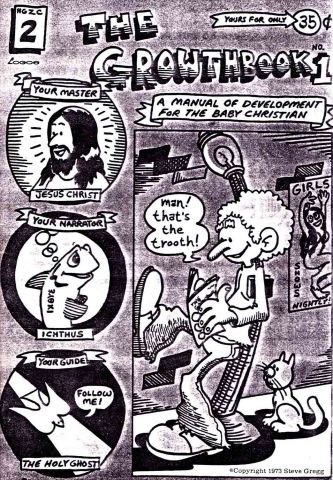

Holy Ghost Zapped Comix. Another blast from the 70s, these saved-hippie volumes are obviously a Christian gloss on the underground comics scene: What if Robert Crumb got saved and his Zap Comix were used for evangelism and discipleship? Steve Gregg brought that do-it-yourself aesthetic to four issues of this 40-page series: Holy Ghost Zapped Comix, The Growthbook, New Creature Comix, and Jews for Jesus. Bell bottoms abound, along with naked cartoon characters (embarrassing but not indecent), hippie lingo, and an earnestness you could only get from those hirsute Jesus people. Gregg threw himself at these comics with everything he had, and it’s all right there on the page. His mode of Bible exposition included strange dramatic re-tellings of the fall of man, the baptism of Jesus, some parables, and whatever else struck him. There is always plenty of theological commentary on the page, with the narrator’s voice playing straight man so the cartoon characters can deliver one-liners and zingers in slang (“Teacher, where do you crash?”) One recurring character is a bit too obviously a spoof of Crumb’s Mr. Natural, but Gregg’s own talent is considerable, and he quickly finds his own style.

Holy Ghost Zapped Comix. Another blast from the 70s, these saved-hippie volumes are obviously a Christian gloss on the underground comics scene: What if Robert Crumb got saved and his Zap Comix were used for evangelism and discipleship? Steve Gregg brought that do-it-yourself aesthetic to four issues of this 40-page series: Holy Ghost Zapped Comix, The Growthbook, New Creature Comix, and Jews for Jesus. Bell bottoms abound, along with naked cartoon characters (embarrassing but not indecent), hippie lingo, and an earnestness you could only get from those hirsute Jesus people. Gregg threw himself at these comics with everything he had, and it’s all right there on the page. His mode of Bible exposition included strange dramatic re-tellings of the fall of man, the baptism of Jesus, some parables, and whatever else struck him. There is always plenty of theological commentary on the page, with the narrator’s voice playing straight man so the cartoon characters can deliver one-liners and zingers in slang (“Teacher, where do you crash?”) One recurring character is a bit too obviously a spoof of Crumb’s Mr. Natural, but Gregg’s own talent is considerable, and he quickly finds his own style.

More inhibited cartoonists might have paused at the difficult challenges of how to represent God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit, but Gregg just jumped in and did it. Some of his decisions in these Holy Ghost Zapped Comix are cautionary tales for later artists, but his unguardedness as an artist also makes them precious testimonies to how Christianity looked to the Jesus freaks of the time, and how they commended it to the world. These are out of print and very rare. Gregg himself continues a teaching ministry today, and has two comic books available online. They are not the same as his original Zapped books: they’re cleaner and more wordy, but still worth a look. All things considered, it’s probably best that Steve Gregg got a little more uptight, dude, but the original comix are stunningly loose.

More inhibited cartoonists might have paused at the difficult challenges of how to represent God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit, but Gregg just jumped in and did it. Some of his decisions in these Holy Ghost Zapped Comix are cautionary tales for later artists, but his unguardedness as an artist also makes them precious testimonies to how Christianity looked to the Jesus freaks of the time, and how they commended it to the world. These are out of print and very rare. Gregg himself continues a teaching ministry today, and has two comic books available online. They are not the same as his original Zapped books: they’re cleaner and more wordy, but still worth a look. All things considered, it’s probably best that Steve Gregg got a little more uptight, dude, but the original comix are stunningly loose.

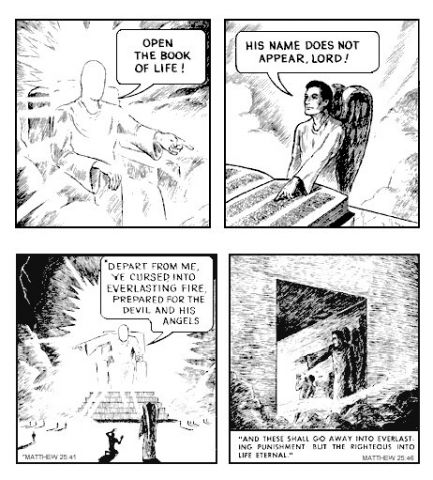

Chick Tracts and Comics, by Jack Chick and Fred Carter. Those little booklets, sometimes it seems like they are everywhere! Jack T. Chick is an unstoppable producer of cartoons, hundreds of pamphlet tracts in scores of languages, shipped out by the hundreds of millions (!) for four decades. Chick is a natural communicator, and in his earliest tracts he hit on a handful of unforgettable symbols. This Was Your Life is the ur-text: A man in his prime keels over suddenly, is flown to heaven by an angel, and stands naked before a gigantic God seated on the throne of judgment with a face too bright to behold, where he is forced to watch a movie of his entire life in real time on a colossal screen. Could God’s omniscience be presented any more viscerally for a twentieth-century audience? A handful of Chick’s early tracts will stay in the Christian sub-consciousness forever, I think.

Chick Tracts and Comics, by Jack Chick and Fred Carter. Those little booklets, sometimes it seems like they are everywhere! Jack T. Chick is an unstoppable producer of cartoons, hundreds of pamphlet tracts in scores of languages, shipped out by the hundreds of millions (!) for four decades. Chick is a natural communicator, and in his earliest tracts he hit on a handful of unforgettable symbols. This Was Your Life is the ur-text: A man in his prime keels over suddenly, is flown to heaven by an angel, and stands naked before a gigantic God seated on the throne of judgment with a face too bright to behold, where he is forced to watch a movie of his entire life in real time on a colossal screen. Could God’s omniscience be presented any more viscerally for a twentieth-century audience? A handful of Chick’s early tracts will stay in the Christian sub-consciousness forever, I think.

But Chick fell from the grace of the mainstream pretty early, and the more he developed his message, the more uncomfortable he made most Christians. Chick is a conspiracy theorist, and when it comes to the satanic plan to oppose God’s work in the world, all roads lead to Rome. The pope is not only the antichrist, he’s pushing death cookies, monitoring Protestant activities, assassinating his opponents, and masterminding the overthrow of the King James Version so nobody will have access to the truth. In the heyday of the Christian bookstore, you could gauge how far to the right a store was by which Chick tracts they would stock. His worst stuff embarrasses even people who would be inclined to agree with him. You can hear them saying, “Well, heck, I’m an anti-Catholic KJV-only separatist fundamentalist just like the next guy, but some of that Chick stuff is just crazy!”

But Chick fell from the grace of the mainstream pretty early, and the more he developed his message, the more uncomfortable he made most Christians. Chick is a conspiracy theorist, and when it comes to the satanic plan to oppose God’s work in the world, all roads lead to Rome. The pope is not only the antichrist, he’s pushing death cookies, monitoring Protestant activities, assassinating his opponents, and masterminding the overthrow of the King James Version so nobody will have access to the truth. In the heyday of the Christian bookstore, you could gauge how far to the right a store was by which Chick tracts they would stock. His worst stuff embarrasses even people who would be inclined to agree with him. You can hear them saying, “Well, heck, I’m an anti-Catholic KJV-only separatist fundamentalist just like the next guy, but some of that Chick stuff is just crazy!”

Beyond the tracts, Chick also published several full-sized, full-length comic books, drawn in a much richer and less cartoony style of rendering. For years, many people assumed that Jack Chick was capable of drawing in two distinct styles, but eventually the mysterious artist was revealed: he is Fred Carter, an African-American pastor from Chicago. Carter is the artist responsible for about half of the Chick tracts and all of the full-size comic books, plus the 360 paintings used in the Chick film Light of the World.

Beyond the tracts, Chick also published several full-sized, full-length comic books, drawn in a much richer and less cartoony style of rendering. For years, many people assumed that Jack Chick was capable of drawing in two distinct styles, but eventually the mysterious artist was revealed: he is Fred Carter, an African-American pastor from Chicago. Carter is the artist responsible for about half of the Chick tracts and all of the full-size comic books, plus the 360 paintings used in the Chick film Light of the World.

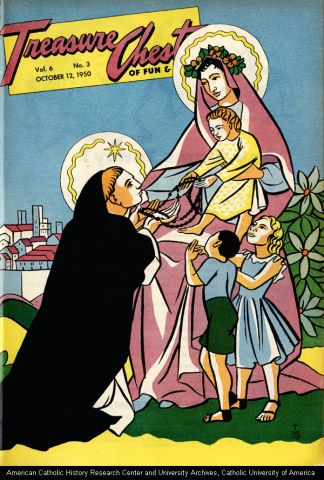

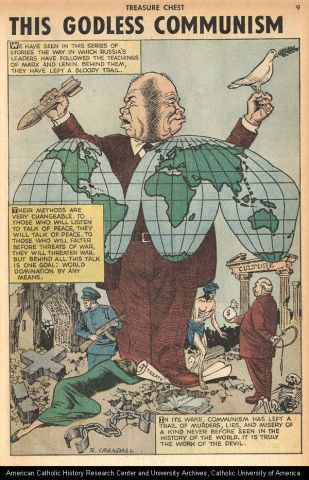

Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact. Catholic publisher George Pflaum started this comic book in 1946, and cranked out more than 500 issues of it by 1972, usually at the rate of one issue every two weeks. To be honest, a lot of it is pretty awful cartooning, and you can imagine that it would only sell in a parochial market to a captive audience. And to make matters worse, a lot of the material isn’t specifically Christian, it’s just guaranteed to be safe for kids: sports heroes, stories of small town life, folk tales, exemplary youth avoiding juvenile delinquency. Bleh, mostly.

Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact. Catholic publisher George Pflaum started this comic book in 1946, and cranked out more than 500 issues of it by 1972, usually at the rate of one issue every two weeks. To be honest, a lot of it is pretty awful cartooning, and you can imagine that it would only sell in a parochial market to a captive audience. And to make matters worse, a lot of the material isn’t specifically Christian, it’s just guaranteed to be safe for kids: sports heroes, stories of small town life, folk tales, exemplary youth avoiding juvenile delinquency. Bleh, mostly.

But evenly distributed throughout those thousands and thousands and thousands of pages, there are some wonderful things. First of all, a number of established cartoonists did work for Treasure Chest: Reed Crandall of EC, Joe Sinnott of DC, and many others.

More importantly, while Treasure Chest may have been weak at producing original fiction, it was committed to doing plenty of non-fiction as well. So there is history, theology, science, current events, social issues, and all sorts of other stuff that mainstream comics, with their obsession for genres like superheroes, cowboys, and romance, didn’t even try to do. Treasure Chest explored territory that no other comic ever did. Much of the Christian and biblical material is profitable for all believers, but a minority of it is so specifically, insularly Roman Catholic that it is less helpful for anybody else.

More importantly, while Treasure Chest may have been weak at producing original fiction, it was committed to doing plenty of non-fiction as well. So there is history, theology, science, current events, social issues, and all sorts of other stuff that mainstream comics, with their obsession for genres like superheroes, cowboys, and romance, didn’t even try to do. Treasure Chest explored territory that no other comic ever did. Much of the Christian and biblical material is profitable for all believers, but a minority of it is so specifically, insularly Roman Catholic that it is less helpful for anybody else.

It’s a baffling array of material. You can browse it online here, though a more helpful catalog system is here.

While there’s plenty to love in these five comic book projects, I finish this retrospective with the impression that the medium has not been used as effectively as it might have been. Are there Christians working today who understand the potential of the comic book medium for education and ministry?