I have committed my life to helping people understand the doctrine of the Trinity, and especially to seeing how it is relevant to their spiritual experience. I think it is a profoundly biblical doctrine, a reasonable thing to believe, the solution to numerous theological difficulties, and a powerful boost to spiritual insight.

I have committed my life to helping people understand the doctrine of the Trinity, and especially to seeing how it is relevant to their spiritual experience. I think it is a profoundly biblical doctrine, a reasonable thing to believe, the solution to numerous theological difficulties, and a powerful boost to spiritual insight.

But I don’t put much stock in the word “Trinity” itself, a word which is not directly biblical and not strictly necessary. It’s a word that sounds abstract, algebraic, Latin, maybe even Roman Catholic to some ears. If it’s helpful to use the word, I use it; when it’s not, I don’t fight about it. I’d die for the doctrine, but not the word. And above all, if I had to choose between the word and the thing itself, I’d take the thing itself.

For example, last week I attended the Wheaton Theology Conference, which was dedicated to the doctrine of the Trinity this year. It was, as usual, a thoughtfully-planned and well-run conference, and the Trinity is surely the right topic to gather around for theological discussion. Everyone who attended got to hear hours of interesting presentations on the Trinity, the Trinity, the Trinity, the Trinity. I bet we heard the word at least once per minute during every waking hour of a three-day conference.

Then I came home and attended church, where we’re several months into preaching through the book of Romans. The pastor preached a solid exposition of Romans 8:10-17, which meant he talked about Christ indwelling the believer, the Spirit of Christ being in us, and our crying “Abba, Father” as a result of being co-heirs with Christ.

He never said the word Trinity once, but the sermon was every bit as trinitarian as anything I heard at the theology conference. And in some ways, it was even better: Nobody left wondering, “But how is the Trinity relevant to my life?” because everybody heard it in directly biblical terms. The Father has adopted us, the Son has joined us to himself in his suffering and glorification, and the Spirit dwells in us. We heard the gospel, and heard the Trinity in it. We heard the thing itself, the one God in three persons saving us. Having heard the three persons, we didn’t need to hear the three syllables. That’s how most preaching on the Trinity probably ought to be.

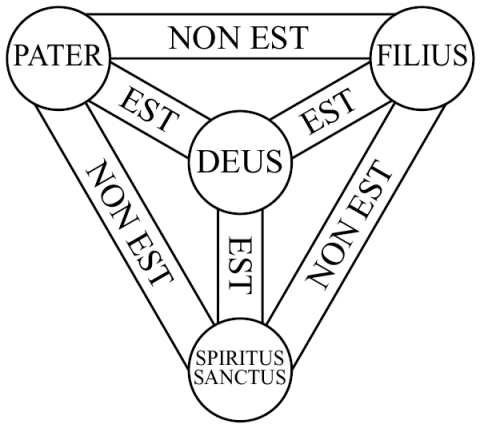

Of course, it’s still very helpful to know that the pastor is in a church that believes in the doctrine of the Trinity with all its well-ordered truth claims: that each of the three persons is fully divine, and they are not each other, and there is only one God. It also needs to be said that God is not just putting on different masks for different tasks, or slipping into different modes for different moods, but that the one God eternally exists in these three persons, and would do so if Christ and the Spirit had never been sent, if the world had never been created, if there were nothing but God. And now and then we’ll be glad to use the word “Trinity,” which healthy-minded Christians have been happy to use for at least nineteen centuries as a brief summary of all those truth claims in their right relations.

Anybody who believes all the truth claims but refuses to use the T-word is, I think, a little bit cranky, or overly scrupulous, or has a bad attitude toward tradition. On the other hand, some people refuse to use the T-word because they reject one of the truth claims it summarizes: they think Jesus isn’t fully divine, or they think the Father and the Son are one person, or the Spirit is a force field, or something equally far afield from the truth of the Bible. To these people, I happily say: TRINITY! TRINITY! TRINITY! Booga booga booga! This clarifies our positions instantly, and saves a lot of time.

If you want to read something better than a blog post about this, go read Calvin’s wise and classic discussion of this in Institutes Book I, chapter 13, section 5. He doesn’t say “schminity,” but he does say that he could wish all non-biblical terms thrown into the sea, if only all Christian teachers would truly mean the right things by the way they use biblical words.

And sadly, I’m not the first to use the word “schminity.” This unusual anti-trinitarian artist uses it several times toward the middle of the song, a song which I hope will cause anybody who hears it to think that whatever this fellow is against might be worth considering. (Jump to about 2:28 if you can’t endure the whole build-up.)