To keep the work of theology at its proper task, and to keep the theologian from getting distracted, and to keep the main thing the main thing (which is, after all, itself the main thing), there are a couple of helpful rules to observe.

They are pretty simple and obvious. Here they are: Make sure that every substantive theological statement is connected to God, and make sure every substantive theological statement is connected to the gospel.

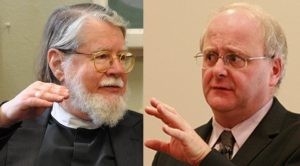

I’ve come to associate these two rules with two theologians who have died in the last couple of years: Robert Jenson (d. 2017) and John Webster (d. 2016).

Jenson said that since theology is “interpretation at the turn from hearing to speaking the gospel,” we can write theology by following a rule that has this form: “to be saying the gospel, let us say ‘F’ rather than ‘G.”

That F-G business is algebraic: he means that every time we theologize, we should ask what kind of statements will result in a statement of the gospel. Theologians can do that because they have heard the gospel, and there “at the turn from hearing to speaking” they can figure out which new statements will succeed at stating the gospel, and reject the ones that wouldn’t. As Jenson worked this out in his Systematic Theology, it seemed to me that he was trying to handle every single doctrine and sub-doctrine in such a way that he was saying the gospel in the very act of saying that doctrine, no matter what it was. This is a tall order, but I think is a rule that ought to be running in the background of all theological work. I know I’ve watched Calvin apply it: you can tell that in the Institutes, when he decides how much to say and how much to leave unsaid about a topic like angels, he is asking himself, “How can I talk about angels and be saying the gospel?” (He manages, by the way: check it out.)

That’s the gospel rule. The other rule, which I primarily associate with John Webster, is the God rule. It’s hard to believe that theologians need to be reminded to talk about God, but we really do. It is unfortunately very easy to be drawn into all kinds of theological chatter about all sorts of topics. Webster declared his program to be “theological theology,” which was a strange way to remind himself and others that theology has to be about God at all times. Webster often said that theology was about (1) God and (2) all things in relation to God. To drive the point home yet again, he quipped, “Theology is about everything; But it is not about everything about everything, But about everything in relation to God.” Done right, theology is one long journey inside the doctrine of God, which just happens to be so expansive as to include all things in relation to God.

The difference these two rules might make in carrying out the work of theology is this: any theological topic, no matter how small or detailed or partial it might be, is subject to dogmatic mapping. It can and should be located with regard to the major landmarks of the theological landscape. One way to locate a doctrine is to look to its immediately neighboring doctrines. But the main way is to locate it with reference to the two major doctrinal fields: God and the gospel.

If we take Jenson and Webster as especially pure or striking advocates of the two rules, we could note the ways they agree and disagree, or gave each other fits of worrying about how to work with these rules. Webster increasingly wanted the doctrine of creation to exert more normative influence on all theological statements; Jenson often exerted himself mightily to ensure there was no leftover God for anybody to talk about anywhere except in the gospel. Their respective theological projects illuminate several of the possible relations between the two rules; both of these theologians worked under the influence of both rules. All theology ought to do so, and to draw out the consequences for every single doctrine in the entire field of Christian truth.