This speech was originally given on March 3, 2016, by Professor Eva Brann of St. John’s College (Annapolis), as part of the Distinguished Lecture Series at the Torrey Honors Institute. The following is an excerpt. A link to her full speech is available on Open Biola.

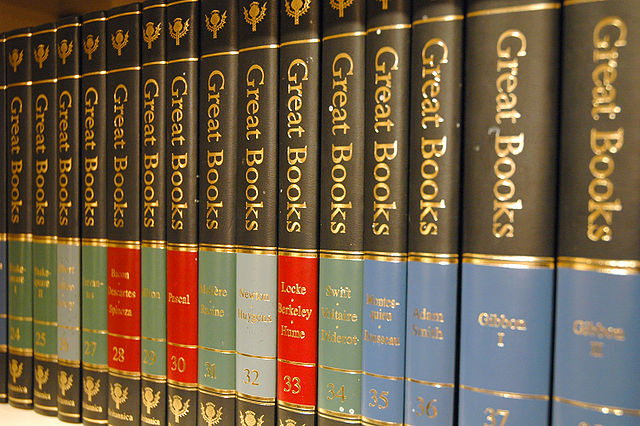

There’s reading and then there’s reading. There’s the kind called texting, done on a minuscule tablet with a limit to the cyphers used, which has in effect given up the ghost of significance. Then there’s the kind of easy feed, the best-seller, which we scarf up in a state of pleasant relaxation. Then there’s the instruction booklet, infinitely annoying, because widget A never does fit into aperture B. I won’t attempt to list all the types of reading we do, but instead I’ll leap to the list of books to which your program of learning is in fact devoted. These books all share one characteristic: They are demanding. They’re not taken up lightly, nor do they go down easily, nor are they irritatingly inscrutable. They are, instead, difficult. All require your undivided attention and repay it with insights that are at once new to you and also welcome to your intellect. They deliver adventitious, that is, novel, matter which nevertheless immediately sits well in your intellect – or rouses energizing opposition. Such books have a collective name: They’re great.

So, why read books, and moreover, why read great books?

One. Great books held in common and conversation about them is the cause of the warmest, most long-lasting, least problem-fraught friendships life has. The friends you room with, work with, play with come and go as the occasion arises and falls apart; reading friendships survive the decades.

Two. The purpose of reading is to appropriate life, so why not just live it, now? Why read books rather than live reality? I think that we have layered souls. If you like, our souls are stratified; so also is the world stratified. It has a surface layer: the way things in general look on their outside, their surface appearance. Both our souls and our world challenge us to dig into them, to penetrate the surface. Here is what books do: They help us penetrate into ourselves and into the world.

Three. Great books help us do what we can’t do for ourselves; they are our supporters in a life-enhancing activity. But once again: Why turn to books rather than directly to life itself? In the end we have to do it all by ourselves, for ourselves. Why not face ourselves and our world inthat direct way? Here’s the answer, straight and harsh: We’re not up to it. Most of us, you and I and your professors, faced with all that is within and without us, simply shut down or take to babbling. So we need the boot-strappers, the so-called original thinkers who, though they too have teachers, are able to go beyond them on their own.

Four. Great books are affirmative: they give us a chance at working out a picture of happiness. What is the relation of great works to the experience of happiness? It is a very close one. Think of Augustine’s Confessions: The author experiences and meticulously describes his sins and agonies—but the reading of it is grippingly exhilarating. Think of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, whose hero descends into all the horrors and miseries of a tyrannical soul—but the watching of it is grandly awesome. Great books can depict a world that is hostile, souls that are stricken, fates that are terrible. But they are not just depressing, repulsive or frightening. They are, by their very greatness, affirmative. It’s a characteristic I’m sure of but endlessly puzzled by.

Five: the toning of the soul, which follows from the affirmative nature of greatness. People who have the mandate and the leisure to think, to study, to foster the spirit, are especially prone to what medieval monks called acedia, a kind of spiritual moping, a revulsion from accepting the very blessings for which they really long. All students who don’t study like automata know it. Its mild form is the inability to pull yourself together, to get down to it; its more serious form is being stalled, distracted, sleepy, mildly – not clinically – depressed. If you can only collect yourself enough to “pick up [the book] and read” (I’m quoting from a crucial event in Augustine’s Confessions) a great book will pull you out of this langour.For such reading requires a dual mind, a kind of sound schizophrenia. You have to entertain within yourself both a critical and a reverent spirit. What I mean is that your critique is not rejection but engagement, that your doubts are honor done a text by close attention. And your reverence, far from being passive submission, is an active faith in the author’s greatness. If only you can bring yourself to sit down to it, reading great books arouses your vital spirits.

Six and lastly. In cyberspace, where many of you probably live a large part of your life, you find a veritable flood of imagery. This mudslide threatens to swamp and suffocate our mysterious power to form mental images, to see internally, to re-view within what we remember having seen, or even to produce pictures of what we’ve never seen. This capacity, absolutely necessary to a livable inner life, is threatened by the electronic image tsunami. Now think of books. If, when reading, I come across a few figure plates, I, for one, usually say to myself: “That’s not how she”—say Natasha Rostov in War and Peace—“looks at all; I’ve seen her.” Seen Natasha? Where? In my imagination, of course, in my mind’s eye. Verbal texts incite, demand internal visualization.

This is a good place to end, though of course there are more good reasons for reading. It’s, in fact, the best place to stop, because if texts of words are indeed exercises in visualization, in actively generating our own images from well-wrought words, if they are in fact exercises that prevent us from passively succumbing to other people’s pictures and their self-serving agendas, then we might conclusively say of reading the best of books: They cooperate in saving our souls.