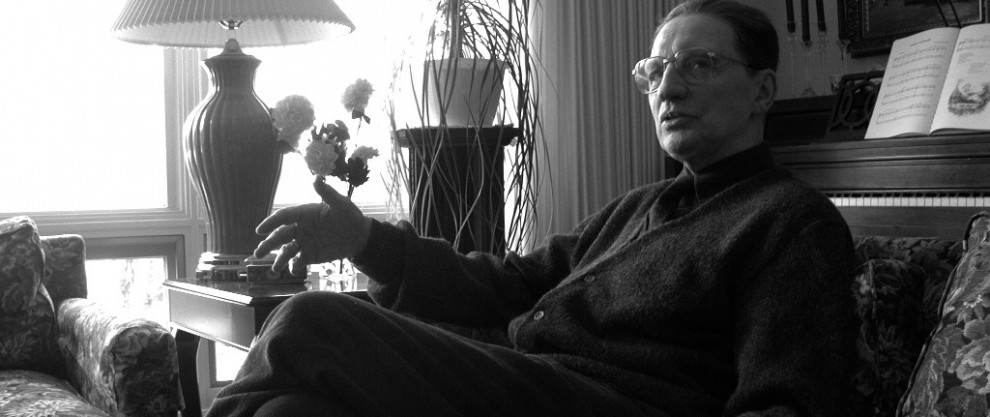

Wolfhart Pannenberg, retired from a long theology career at Munich, has died at age 85.

Pannenberg was a major twentieth-century theologian by any count, with a series of brilliant articles, important books on the topics of revelation, christology, ethics, science, anthropology, and metaphysics, and a hefty 3-volume Systematic Theology to cap off his career.

Pannenberg was a theologian of history in three senses: first, the concept of history was central for his constructive thought (more on this below), and second, he always always situated his doctrinal deliberations within the history of ideas; so although his writing was fairly clear (and English translations were always timely), his meticulous style of argumentation was too consistently demanding to attract very many readers without considerable academic training. And third, Pannenberg was a theologian of history in the further sense that he made history: his work is a monumental achievement of late twentieth-century theology. To some audiences, his Systematic Theology began to seem dated as soon as it was published, but theologians ignore it at their peril. Even where Pannenberg is judged to have taken a wrong turn, he was so thorough and explicit in his decisions that his errors are instructive. And wherever he was on the right track, those same merits make him a uniquely useful guide.

In the Fray, Thinking More Comprehensively

Pannenberg’s characteristic theological posture was to lean in to challenges, in order to come directly to terms with objections to Christian faith. He identified the chief temptation for modern theology as the temptation to hide from the conflict of ideas, imagining itself to be dwelling safely in some sort of zone of immunity, some shelter from harsh warfare and heavy weather. His project was essentially an apologetic one, and that put him, self-consciously and intentionally, at odds with the influence of Karl Barth.

But if Pannenberg was fundamentally an apologist, he went about the task in such a comprehensive way that his apologetic had none of the ad hoc or reactionary character of many apologetics projects. He never gave the impression of someone waiting to see what the world’s questions were. Instead, his intention was to think about reality itself in such a comprehensive way that his theology was always occupying a higher conceptual ground than the ground from which objections were launched.

Theology as Ultimate Truth about Everything

In Pannenberg’s view, the dominant schools of midcentury Protestant theology were too focused on the life of faith itself, and he wanted to redirect attention to the proper subject of theology: God, and everything in relation to God. As he reflected in a 1988 autobiographical essay, “I soon became persuaded that one first has to acquire a systematic account of every other field, not only theology, but also philosophy and the dialogue with the natural and social sciences before with sufficient confidence one can dare to develop the doctrine of God.”

And he meant it. As Michael Root noted not long ago in a great essay in First Things,

Pannenberg’s project is breathtaking in its audacity. The theologian must stand ready, at least in principle, to discuss every topic. “A doctrine of God touches upon everything else. Therefore, it is necessary to explore every field of knowledge in order to speak of God reasonably.” Theology so understood seems to require a universal genius, a Leibniz or a Newton. Pannenberg’s range of knowledge is so extensive, one is tempted to believe the job possible.

Ever since Pannenberg’s work emerged in the 1960s, it was obvious he was up to something exciting. Observers had some trouble categorizing him: he talked about the future so much, perhaps he was part of the “theology of hope” movement. He was a respected German academic who actually believed in the resurrection of Jesus, perhaps he was part of a return to orthodoxy (though as William C. Placher pointed out, “the salient point of even his earlier work was not that he believed in Jesus’ bodily resurrection but that he believed one could argue for it”). But as he published more and more ambitiously, his real program became clearer. Stanley Grenz was on the scent in an article where he called Pannenberg’s project “the classical quest for ultimate truth in the midst of contemporary, post-Enlightenment culture.”

Confident and Open to Criticism

It’s hard to miss the fact that Pannenberg believed that Christianity is true, and that it could be shown to be true when exposed to critical scrutiny. So he welcomed critique from outside, and he rejected any attempt on the part of Christians to avoid such critique:

The tendency toward a subjectivization and individualization of piety…expresses itself in an especially crass way in the usual structure of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is widely taken as a catchword for the view that the content of faith is present only for the pious subjectivity, so that its truth cannot be presented in a way that can claim universal binding force…The Spirit of which the New Testament speaks is no asylum ignorantiae for pious experience, which exempts one from all obligation to account for its contents. The Christian message will not regain its missionary power, nor church life its health, unless this falsification of the Holy Spirit is set aside which has developed in the history of piety especially in reaction against the assaults of the Enlightenment.

In his Systematic Theology, Pannenberg described the main task of theology as a critical examination of the truth-claims made by the church. Rather than presuppose the truth of the gospel, Christian theology must systematically force itself to face the question of truth.

Spoiling the Egyptians

Just as the early Christian apologists “spoiled the Egyptians” by laying hold of all truth and claiming it as their own (think of Justin Martyr enlisting Socrates as a witness to Christ), Pannenberg set out to use secular disciplines like anthropology and the philosophy of history in service of Christian truth claims. In these fields, Pannenberg worked hard to learn the language, issues, and methodology of the disciplines thoroughly, and then undertook to show how these sciences are dependent on the reality of God.

But Pannenberg never just grabbed these ideas and said “mine!” He re-thought them from within, until he could show that they had in themselves a tendency toward Christian truth. The relevant examples are pretty complex, but here are two. In grappling with Gadamer’s hermeneutical principle of the interpretive “fusion of horizons,” Pannenberg insisted that Gadamer needed to confess the ontological assumptions behind his view. Texts could only be interpreted in that way if there were a total, universal history really underlying and uniting the texts and their readers. But Gadamer would not affirm that, prompting Pannenberg to write that “it is a peculiar spectacle to see how an incisive and penetrating author has his hands full trying to keep his thoughts from going in the direction they inherently want to go.” Similarly, in his book on anthropology, Pannenberg focused on the widespread anthropological concept of “eccentricity”, or openness to the world, and relentlessly pursued the meaning of this central anthropological concept until he has demonstrated that it finds its best interpretation in “openness to God.” His conclusion was that “the genealogy of modern anthropology points back to Christian theology. Even today it has not outgrown this origin, for as has been shown its basic idea still contains the question about God.” Pannenberg was determined to remind the Western intellectual world of its Judeao-Christian pedigree.

Who’s Got Whom Surrounded?

Taken all together, these Pannenbergian commitments put him in a position to oppose secularism and its critiques of Christianity with a strategy of outflanking. Any attack on the side of your opponent’s forces is a flanking move; but when you flank them on both sides, or on all sides, you’ve really got them surrounded: outflanked all around. Pannenberg was that kind of thinker. He surrounded his opponents by thinking bigger, by pushing every question to a more comprehensive level.

And when you outflank your opponents thoroughly enough in an intellectual contest, you find out they’re not primarily opponents after all, at least not in the straightforward sense that a frontal assault would have presupposed. What Pannenberg worked toward was a comprehensive quest for truth in all the disciplines that seemed most important for Christian witness, and he found himself engaged in conversations about the nature of reality, of history, of humanity, with a distinctively Christian contribution to make to those discussions.

Pannenberg’s outflanking strategy had its pluses and minuses; as I write this appreciation the day after his death I am mainly thinking of the pluses. He gave to theology an impulse to engage in the public discussion of its truth claims rather than to flee to a private, inward, indefensible safe zone. It was an impulse toward reality, and a confidence that the road to reality, pursued with intellectual honesty and rigor, would lead to Christ, in whom all things hold together, in whom are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. That is a great stimulus to have given theology, and it could only have been given by someone polymathic enough to carry out a big part of the program singlehandedly. It’s hard to think of anybody quite like him among contemporary theologians, and he will be missed.