There’s an old joke, “How do you say ‘Happy Easter’ in Russian?” Answer: “Christ is Risen.”

It’s a good joke, because it shocks by re-intruding the religious content into a word (Easter) that does a good job sounding, to most of its users, more neutral than religious. Somewhere in the long, strange history of the English language, all the obvious religious significance got worn off of our conventional word for the celebration of the resurrection of Christ. We say “Easter,” the Germans say Ostern, but almost every other member of the family of western languages uses some version of “pascha:” French Pâques, Italian Pasqua, Spanish Pascua. Never mind how we got stuck with this word; English is full of such oddities (consider our bizarre little word “church” where all the other languages have some form of ekklesia: eglise, iglesia, chiesa), and never mind the conspiracy theories about worshiping Ishtar. Sober etymology is possible here, but beside the point. As words go, “Easter” doesn’t do quite a good enough job of pointing to the thing it’s supposed to point to.

It’s a good joke, because it shocks by re-intruding the religious content into a word (Easter) that does a good job sounding, to most of its users, more neutral than religious. Somewhere in the long, strange history of the English language, all the obvious religious significance got worn off of our conventional word for the celebration of the resurrection of Christ. We say “Easter,” the Germans say Ostern, but almost every other member of the family of western languages uses some version of “pascha:” French Pâques, Italian Pasqua, Spanish Pascua. Never mind how we got stuck with this word; English is full of such oddities (consider our bizarre little word “church” where all the other languages have some form of ekklesia: eglise, iglesia, chiesa), and never mind the conspiracy theories about worshiping Ishtar. Sober etymology is possible here, but beside the point. As words go, “Easter” doesn’t do quite a good enough job of pointing to the thing it’s supposed to point to.

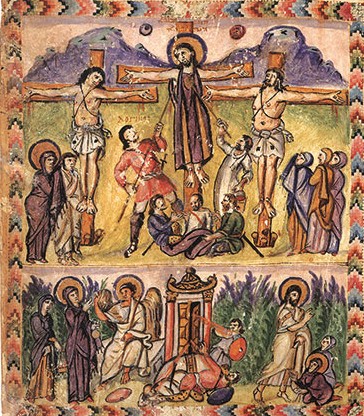

Here’s why: We celebrate Easter Sunday in the same extended, multi-day period where we celebrate the death of Christ. There is a profound reason for that: crucifixion and resurrection belong together. It would be bizarre to commemorate the crucifixion by itself, say in August, and then wait for another section of the Christian calendar to celebrate the resurrection. So from the most ancient times, Christians have crept up to Good Friday and kept the solemn observations going on through Holy Saturday to Resurrection Sunday. But from a distance, we call the whole thing “Easter,” which leaves us –again, in English only– with a word that mainly points to the Sunday part of it. “Easter” somehow signifies the whole three-day event, but also the end of it.

I suppose we could start calling it “the Triduum,” the Three-Day, but introducing Latin in mixed company has disadvantages. What we need is a good English word that captures the whole run from Good Friday to Easter Sunday.

Which brings us back to pascha and its modern derivatives. It comes from Greek, and in the New Testament it’s referring back to a Hebrew word for the Passover (Ex. 12). In New Testament usage, pascha never quite points to a distinctively Christian feast; it remains part of the shared vocabulary of those who do and those who do not see the passover as fulfilled in Christ. The earliest Christians were Jews who continued to keep the Passover feast, but with the pervasive difference that their experience of the death and resurrection of Christ had made. But the trajectory of its usage was obvious, and it was readily picked up in Christian language and used to refer to death and resurrection of Christ. In the second century, Melito of Sardis’ magnificent little work On the Pascha begins with the Passover and connects all the dots to the death of Christ.

So pascha, or some less exotic-sounding anglicizing of it, might be an option for English Easter-talk. It has the great advantage of drawing us back into the matrix of biblical usage, calling to mind the deliverance of Israel from Egypt, the apostles’ experience of the ritual meal’s fulfillment by Jesus, and more. You really have to put on your mental sandals and take a journey to Bible times to say and hear pascha well. But it has the disadvantage of sounding exotic and ostentatious, of drawing attention to itself rather than the reality it wants to signify. To say pascha in polite anglophone company is to reject the easy flow of common language and instead to lecture your hearers, more or less gently, on a new term they’d better learn if they want to be biblically correct.

Eastern Orthodox Christians in the English-speaking world know the ups and downs of this experience: “Your people call it Easter, but my people call it Pascha,” which can sound like “I am a strange visitor from another place, and none of your words quite capture the exquisite otherness of my culture of origin. There is much you must un-learn before our minds may meet.” This can of course be its own kind of witness, and certainly a conversation piece. But it functions by friction, not fluency. As a rule of thumb, you only get to teach people new vocabulary on special occasions, and when you do that kind of teaching, you are spending social and interpersonal capital. We put up with that kind of thing from technicians and doctors, but we also tend to avoid them if we can.

If Latin (Triduum) and Greek (Pascha) aren’t simple fixes, how about elaborate, hyphenated compounds? We could talk about the Crucifixion-and-Resurrection and its annual ritual recognition. We could blend up a portmanteau, like Crosster, or Crucirez, or Good FriSun, or Threester Sunday.

No, those are all terrible.

This has been a failed thought project about English words and usage, but in this case, words aren’t the main thing. What matters is that we recognize the unity of Christ’s saving work in those final, culminating days of his life on earth: he died, was buried, and rose again. “The final days of Jesus” is a good phrase, and the new book by that name by Andreas Köstenberger and Justin Taylor is a model of patient attention and exposition of what Jesus said, did, and suffered from his entry into Jerusalem on March 29 to his resurrection on April 5, AD 33.

We celebrate it every year in a connected series of worship services that go from at least Good Friday through Easter morning (Palm Sunday, of course, marking the more extended period). The unity of the event matters, and the unity of our celebration of it matters. You can’t have the crucifixion without the resurrection, and vice versa. It would be very useful to have more adequate, flexible, portable, and powerful language for it in English. But the terms aren’t the main thing. There are other ways to recognize, participate in, and communicate the fundamental unity of Jesus’ death and resurrection.