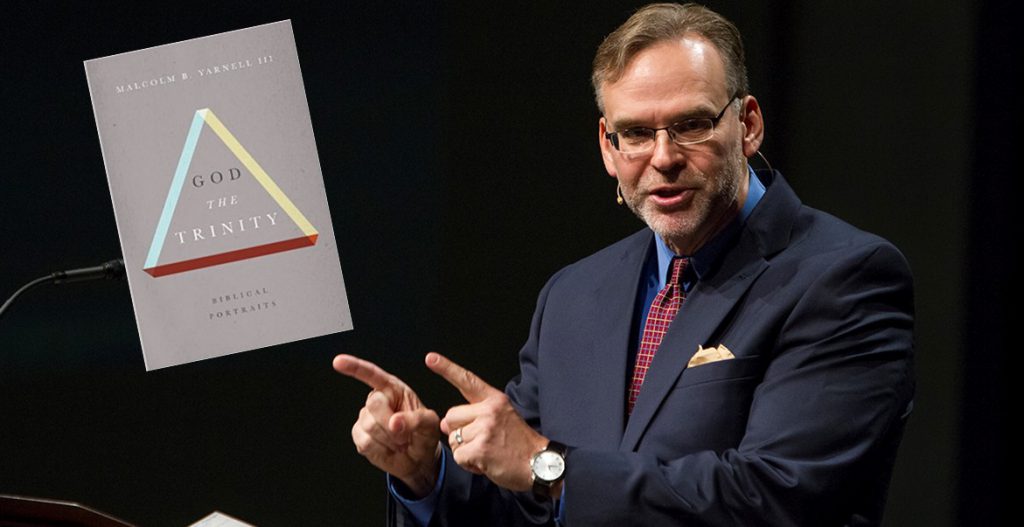

Malcolm Yarnell recently published God the Trinity: Biblical Portraits (B&H Academic, 2016). Yarnell, who is Research Professor of Systematic Theology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, has previously written a fine study on The Formation of Christian Doctrine, among other things.

Malcolm Yarnell recently published God the Trinity: Biblical Portraits (B&H Academic, 2016). Yarnell, who is Research Professor of Systematic Theology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, has previously written a fine study on The Formation of Christian Doctrine, among other things.

I knew Malcolm had been at work on a Trinity book for a while, had been looking forward to it, and was glad to see it published at last. Here’s what I said in my endorsement of God the Trinity:

There is no task more important in contemporary trinitarian theology than that of clarifying its biblical character. Count Malcolm Yarnell among the theologians who have rightly identified this, and watch how he throws everything he’s got into the task. This book engages the Bible’s trinitarian idiom creatively, and summons evangelical theologians and Bible scholars to join in the joyful work of learning to discern just how deeply and directly God the Trinity has spoken in Scripture.

And I meant it!

Yarnell carries out eight close readings of key trinitarian texts in the Bible: Matt 28:19, 2 Cor 13:14, Deut 6:4-7, John 1:18, John 16:14-15, John 17:21-22, Eph 1:9-10, and Rev 5:6. But he doesn’t handle these as proof texts. In each case, he selects the passage in order to launch a broader examination of trinitarian phenomena that characterize the entire Bible’s teaching. And the footnotes point all over the place in the best sense, drawing in exegetical, historical, and doctrinal sources from far and wide. There’s great stuff here on page after page.

I had several questions, mostly methodological, about Yarnell’s book, so I asked him if he’d answer a few of them here on the blog. He agreed, and here’s the resulting interview.

FS: You mention in the prologue that you almost gave this book the subtitle “The Trinitarian Revision of Biblical Hermeneutics,” and I can think of at least two types of hermeneuts you’ve targeted for revision. One would certainly be academics using that cluster of historical-critical limitations that make it impossible to read the Bible as God’s word. But you’re also taking aim at what you call “the method of Bible study many evangelicals are taught to use,” which you say, “must be substantially revised if the Trinity and the Bible are to coalesce.” What are the chief revisions you have in mind?

FS: You mention in the prologue that you almost gave this book the subtitle “The Trinitarian Revision of Biblical Hermeneutics,” and I can think of at least two types of hermeneuts you’ve targeted for revision. One would certainly be academics using that cluster of historical-critical limitations that make it impossible to read the Bible as God’s word. But you’re also taking aim at what you call “the method of Bible study many evangelicals are taught to use,” which you say, “must be substantially revised if the Trinity and the Bible are to coalesce.” What are the chief revisions you have in mind?

MY: Thank you for granting me the opportunity to interact with the person I believe is contemporary evangelicalism’s leading Trinitarian scholar. […]

MY: Thank you for granting me the opportunity to interact with the person I believe is contemporary evangelicalism’s leading Trinitarian scholar. […]

With deference granted, let me try to answer your question, which is important for our following conversation. Please understand that I use the term “evangelical” with a more complex historical perspective than is typical. Allow me to provide a short taxonomy for the term, “evangelical.”

First, “evangelical” from a biblical perspective means any church or person who takes the “euangelion” (Greek for “gospel”) centered in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ as fundamentally transformative of reality. The way I use “evangelical” in the book presumes this broad and necessary sense, but like most contemporary evangelicals, my definition of “evangelical” is still narrower than that of mere Christianity (cf. C.S. Lewis).

Second and more to the point, while some primarily restrict the sense of “evangelical” to the huge revivals that began in the eighteenth-century English-speaking world or to the fundamentalist-modernist debates of the twentieth century, I believe contemporary evangelicalism is necessarily rooted in the sixteenth-century. Evangelicals rightly trace their origin to the Reformation rediscovery of justification by faith, sola scriptura, and the universal priesthood. The second of these Reformation distinctives, sola scriptura, requires evangelicals to use the Bible to get behind tradition back to the truth. It is necessary to our Reformation faith to question the history of the church and return constantly to a fresh reading of the biblical text. But without the church’s tradition to depend upon, we are left, from a human perspective, nearly alone with the words of the historical canon.

Because of this basis, “evangelical” includes all of those who are defined by Reformation commitments, including both Magisterial Protestant Churches and Free Churches. Evangelical is thus a proper descriptor not only for contemporary evangelicals but also for “liberals” on the one hand and “fundamentalists” on the other. Evangelicals subsequently had to deal with the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Enlightenment forms of thought, including Enlightenment forms of Bible study, affected evangelicals of all types, though some embraced these forms more readily. German theologians recognize this phenomenon and sometimes use two words to differentiate those “Evangelical” churches who are descended from the Reformation but are generally more appreciative of the Enlightenment, Evangelische, as opposed to those evangelical Christians scandalized by some aspects of the Enlightenment, Evangelikale. Perhaps we could use the terms “liberal evangelical” and “conservative evangelical” to make a similar distinction.

Unfortunately, if we differentiate two or more types of evangelicals, the fact remains that even those suspicious of the acidic impact of the Enlightenment have been affected in their approach to Scripture. The desire for “scientific” or “objective” biblical interpretation, shorn of the problems introduced in tradition, is universal across the evangelical academy. As a result, evangelicals, conservative and liberal, give special and primary attention to the historical and linguistic approaches to Bible study. My own book approvingly adopts this very approach, even as I am explicitly aware of some of the problems this method presents in discerning divine writ.

Both the “liberal evangelical” Historical Critical Method and the “conservative evangelical” Historical-Grammatical Method share certain presuppositions about the church’s historic untrustworthiness and the human mind’s natural ability to discern truth, even as they depart from one another in other ways. This is not the place to work out all of the ways in which this is true, but it is to note the phenomenon. One major way in which this common Enlightenment outlook challenges Trinitarian discourse is through favoring propositions to the point that other forms of literary communication are diminished, especially in systematic theology. See Chapter Three’s discussion of “monotheism” for one significant example of how the Enlightenment created difficulties for even conservative evangelicals regarding the Trinity.

Therefore, as a specific answer to your question, one of the chief revisions I have in mind is that evangelicals must recognize that Enlightenment-preferred propositions are not the only means by which God reveals his being, especially his threeness-in-oneness, in Scripture.

FS: Early on (p. 5) you say that “the Bible reveals the doctrine of the Trinity through its own idiom, an idiom that is conducive to typological hermeneutics responsibly deployed.” Can you say a little more about the Bible’s own trinitarian idiom?

FS: Early on (p. 5) you say that “the Bible reveals the doctrine of the Trinity through its own idiom, an idiom that is conducive to typological hermeneutics responsibly deployed.” Can you say a little more about the Bible’s own trinitarian idiom?

MY: Let me state a Trinitarian thesis based on the idiom first, then explain in short how I came to this conclusion. A doctrinal thesis about divine revelation based on the Trinitarian idiom: The Bible is God’s Word inspired by the Holy Spirit. This thesis is relatively uncontroversial to contemporary evangelicals. Why? First, because we believe the Bible is the Word of God. Second, we also believe it was inspired by the Holy Spirit of God.

MY: Let me state a Trinitarian thesis based on the idiom first, then explain in short how I came to this conclusion. A doctrinal thesis about divine revelation based on the Trinitarian idiom: The Bible is God’s Word inspired by the Holy Spirit. This thesis is relatively uncontroversial to contemporary evangelicals. Why? First, because we believe the Bible is the Word of God. Second, we also believe it was inspired by the Holy Spirit of God.

But note that to say “God,” “Word,” and “Spirit” is to speak in a Trinitarian manner through typological names. As the Spirit-inspired Word of the Son from God the Father, the Bible is the means by which God reveals himself as Trinity today. We have used the names of God, Word, and Spirit in such a way that we have drawn connections with the three persons of the Trinity. Why do we do this? Because Scripture as a whole does this. Across both testaments, and in several genres, through many different human authors, the Bible, through typical names for the three persons of the one God, speaks of God and Father, Word and Son, and the Holy Spirit. This is one example of how the Bible has a Trinitarian idiom. The early church’s creeds spoke similarly. God the Trinity gives many more such examples at some length and with more depth.

FS: On page 10, as you’re gearing up to show “through the texts analyzed in this book that the Trinitarian pattern is found across the various literary genres in the Bible,” you quote some things I’ve said to the effect that the doctrine of the Trinity is only rather obliquely revealed in the words of Scripture. I’ve said things like “the Trinity is not yet revealed in the Old Testament, and then is presupposed rather than revealed in the New Testament.” I suspect we don’t disagree very substantially about this. But let me just ask: how directly is the doctrine of the Trinity made known in Scripture?

FS: On page 10, as you’re gearing up to show “through the texts analyzed in this book that the Trinitarian pattern is found across the various literary genres in the Bible,” you quote some things I’ve said to the effect that the doctrine of the Trinity is only rather obliquely revealed in the words of Scripture. I’ve said things like “the Trinity is not yet revealed in the Old Testament, and then is presupposed rather than revealed in the New Testament.” I suspect we don’t disagree very substantially about this. But let me just ask: how directly is the doctrine of the Trinity made known in Scripture?

MY: From what I have read of your work, our theological projects and our ultimate intentions are very close. Where there is perhaps some disagreement is in our respective descriptions of how direct the revelation of the Trinity is. In direct response to your direct question about how directly I perceive the Trinity is revealed in Scripture, I respond: Directly in personal words. God the Trinity reveals himself in Scripture as Trinity, not immediately in the form of a summary proposition but directly through so many other literary forms and through direct discourse with the hearer of Scripture. One of your fellow Californians, Rick Durst of Gateway Seminary, perceived this in his immediate positive response to the epilogue. It is not until the end of the book that one sees all of the cards that have lain upturned in plain sight the whole time—I believe God the Trinity manifests himself directly in Scripture, exegetically and existentially.

MY: From what I have read of your work, our theological projects and our ultimate intentions are very close. Where there is perhaps some disagreement is in our respective descriptions of how direct the revelation of the Trinity is. In direct response to your direct question about how directly I perceive the Trinity is revealed in Scripture, I respond: Directly in personal words. God the Trinity reveals himself in Scripture as Trinity, not immediately in the form of a summary proposition but directly through so many other literary forms and through direct discourse with the hearer of Scripture. One of your fellow Californians, Rick Durst of Gateway Seminary, perceived this in his immediate positive response to the epilogue. It is not until the end of the book that one sees all of the cards that have lain upturned in plain sight the whole time—I believe God the Trinity manifests himself directly in Scripture, exegetically and existentially.

FS: The formative metaphor for your book is that it’s a series of portraits. You use the analogy of a visible pattern to argue “that God as Trinity is the transcendent pattern in the entire Bible, mysteriously revealed in the Old Testament, and more fully revealed in the New Testament.” How did this visual metaphor help you select the texts for your chapters, and how does it help you approach them?

FS: The formative metaphor for your book is that it’s a series of portraits. You use the analogy of a visible pattern to argue “that God as Trinity is the transcendent pattern in the entire Bible, mysteriously revealed in the Old Testament, and more fully revealed in the New Testament.” How did this visual metaphor help you select the texts for your chapters, and how does it help you approach them?

MY: The visual portrait metaphor was selected, not so much for the reason of deciding upon which of the multitude of Trinitarian texts in Scripture to use, but for helpfulness in other ways.

MY: The visual portrait metaphor was selected, not so much for the reason of deciding upon which of the multitude of Trinitarian texts in Scripture to use, but for helpfulness in other ways.

First, the visual metaphor is a legitimate one as seen from Scripture’s own appeal to sight.

Second, the portrait metaphor, I believe, moves the contemporary reader away from exclusive dependence upon Enlightenment-inspired propositionalism and perhaps being more open toward privileging other forms of literary communication.

Third, the portrait metaphor allows me to treat each biblical text according to its own literary properties, just as one would gaze upon a painting by a Caravaggio differently than one would gaze upon an etching by Blake. Finally, the portrait metaphor is helpful in allowing one to see the commonality of the presentation of Godself as Trinity across both testaments and among many genres through the words of many human authors. As an art gallery gathers many paintings, tapestries, and sculptures to create a universal experience, so the book gathers the exegetical fruit from many biblical texts to create a better view of who God is.

FS: What’s your personal favorite chapter in this book? And is there anything you wish you could have included but had to cut in order to make the book the right proportion?

FS: What’s your personal favorite chapter in this book? And is there anything you wish you could have included but had to cut in order to make the book the right proportion?

MY: My personal favorite chapter? It just depends on where I am that day. Scott Swain seemed to like the final chapter the best, and I have to be frank that the eschatological imagery in Revelation 4-5 moves me powerfully, to the point that there are tears when I teach it.

MY: My personal favorite chapter? It just depends on where I am that day. Scott Swain seemed to like the final chapter the best, and I have to be frank that the eschatological imagery in Revelation 4-5 moves me powerfully, to the point that there are tears when I teach it.

As for preferred revision, I want to spend more time with Ephesians 2:19 and Galatians 4:4-6. So, I would add one chapter dealing with these mirroring texts, which demonstrate the internal movement and soteriological dynamics of Trinitarian life. However, if I had opportunity to revise the book, I would first follow my wife’s advice and switch chapters one and two. Karen is right to say that Chapter Two’s exposition of the Corinthian benediction is a simplified exposition that will help the average reader. Chapter One is much more complex. So, if you are setting out to read God the Trinity, read Chapter Two before Chapter One.