This post is just me preemptively sorting out some terminological confusion in academic trinitarian theology, so if you read it and then find yourself asking, “who cares?” you can’t say I didn’t warn you. The answer is, “seven people care.” So if you’re one of those seven, lean in here and looky, because this is kind of cool.

This post is just me preemptively sorting out some terminological confusion in academic trinitarian theology, so if you read it and then find yourself asking, “who cares?” you can’t say I didn’t warn you. The answer is, “seven people care.” So if you’re one of those seven, lean in here and looky, because this is kind of cool.

In his essay “Christology, Theology, Economy” (which I wrote about last week for the Sapientia blog), John Webster says of Christian teaching that its “one complex matter may therefore be divided into (1) God absolutely considered, that is, considered in himself in his inner life as Father, Son and Spirit (theology), and (2) God relatively considered, that is, considered in his outer works and in relation to his creatures (economy).”

In this passage, Webster is marking the distinction between God and everything else, and using the terms “absolute” and “relative” to do so. He is of course riffing on Aquinas’ description of the task of sacred doctrine (Summa Theologiae Ia 1.7 resp.), “All things are dealt with in holy teaching in terms of God, either because they are God himself or because they are relative to him as their origin and end.”¹ It’s one of Webster’s favorite lines from Thomas on the nature of doctrine, and in this essay he exploits it for the purpose of distinguishing the domains of theology and economy.

But for my own usage, I have a little trouble following Webster’s lead and using the terms “absolute” and “relative” to mark this distinction. I’ve found a more helpful way of talking in the works of the post-Reformation Protestant Orthodox theologians. In particular, I’ve benefited from the way they use the terms “absolute” and “relative” to refer to two different things in the doctrine of God proper, before even turning to God’s outer works (creation or salvation).

Lutheran theologian Quenstedt says it very clearly:

The consideration of God is twofold, one absolute, another relative. The former is occupied with God considered essentially, without respect to the three persons of the Godhead; the latter, with God considered personally. The former explains both the essence and the essential attributes of God; the latter describes the persons of the Holy Trinity, and the personal attributes of each one. (cited in H. Schmid, The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, 134)

More tersely, the Reformed theologian Turretin describes the relation between these two tracts of theology: “The absolute consideration of God (as to his nature and attributes) begets the relative (as to the persons).” (Institutes of Elenctic Theology 1:254)

That is to say, the doctrine of God is subdivided into the considerations of God as one (absolute, or concerning the divine nature) and God as three (relative, or concerning the divine persons).

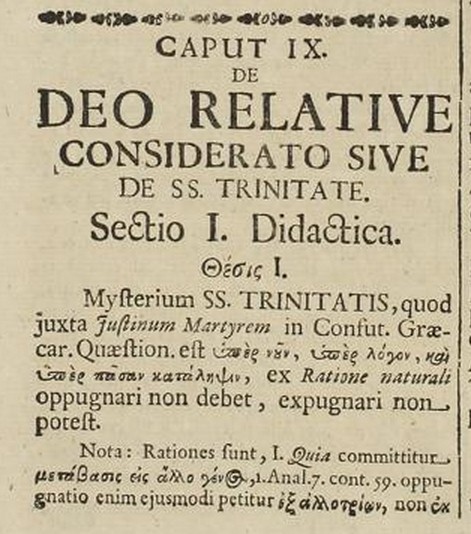

This distinction is basically taken over from Augustine, who explained that Scripture sometimes speaks of God substance-ly and sometimes relation-ly. The advantages of learning to speak this way are enormous: there is payoff in systematic theology (it’s basically the deep grounding for the distinction between de Deo Uno and de Deo Trino, as you can see in the picture from Quenstedt’s dogmatics above), and there is payoff in Bible interpretation as well. It’s also a fascinating way to describe God, as being related internally to himself, or relative to himself in himself.

I discuss this usage, complete with the above Quenstedt and Turretin citations, in my new book The Triune God, on pages 139-140.

So when Webster introduces “absolute” and “relative” for the task of marking the distinction between God and everything else, I demur –not from the distinction, of course, but from the usage. There must be a dozen other ways of marking the distinction between God and everything else. I bet Webster’s own writings are a repository of many of them.

One more note on tidying up terms: Webster in this essay expands the scope of “economy” to include all of God’s outer works, and specifically to encompass both creation and redemption, both nature and grace. I see the benefit of that, but it means swimming against the tide of a pretty widespread use of “the economy” to refer to the history of salvation alone, without including the works of creation. That is probably a fight Webster wants to have, since one of his targets is the way an over-inflation of salvation threatens to transgress the creator-creature distinction, and one way to guard against that is to batch salvation with creation under the heading “things that aren’t God.” The word “economy” hasn’t had a sharply fixed meaning throughout theological history (Tertullian talked about it as an arrangement within God, a usage which really makes a hash of the distinctions we’re making here, and multiplies confusions), so when we use it today we need to pin it down.

________________________

¹In this passage, at least, Thomas doesn’t use the Latin words like “relatio” or “relative” to make his point: Everything in sacred science is handled “sub ratione Dei,” and that is “vel quia sunt ipse Deus; vel quia habent ordinem ad Deum, ut ad principium et finem.” So perhaps this terminological difference isn’t embedded in medieval usage.