Every theologian who wants to think biblically has to believe in providence. Like it or not (and after all, why not like it?), the Bible is about a God who rules and governs world events, from geopolitical reversals to the fate of little birds. This God is not surprised by how things turn out, is not just doing his best with the materials at hand, and is not too distracted to care about details. On the contrary: He’s got the whole world in his hands.

But there are some people who approach the doctrine of providence in an abstract way, and follow their abstraction out to bizarre and unacceptable results. Instead of studying scripture to get a sense of how God works his will through immediate causes, and along with the decisions of human agents, they begin with an axiom as rigid as one of Euclid’s: “Everything That Happens is Done By God.” And they develop that axiom as deductively as a ninth grader who has just learned the word “ergo.” The abstract notion of providence they end up with renders them incapable of getting the right interpretation of (for instance) un-abstract books about providence like Isaiah, and they do even worse at interpreting the course of events in their own lives. What eats away at a soul worse than “pastoral” advice from the school of abstract providence?

Some people teach about providence in a way that suggests that God chose each event and put it into play directly, such that it is a lack of faith to seek explanations anywhere outside of the will of God. Faced with any event, no matter how atrocious, they think the right question is, “Why did God do ______.” Fill in the blank with your favorite tragedy. Soften it to “Why did God allow _____” if you will, but as long as the abstraction haunts you, the question doesn’t really soften.

Who are these “some people” who are teaching this “abstract providence?”

Permit me to sidestep that perfectly good question, by pointing my finger back in time to a group of theologians from the sixteenth century. If anybody ever taught the doctrine of providence in a disastrously abstract way, it was these people. One of their fiercest opponents nick-named them “The Fantastic and Furious Sect of Libertines,” so we can call them FAFSOLs for short. Here is an attack against their doctrine of abstract providence:

Now these giddy people in warbling that God does everything make Him the author of all evil, then later, as if evil had changed nature, since it is covered under the cloak of God’s name, they call it good. In doing so they blaspheme God… For insofar as God has nothing more rightly than His goodness, it would be necessary for Him to deny Himself and to change Himself into the devil in order to perform the evil they attribute to Him. In fact their God is an idol, which we must consider more odious than any idol the pagans knew.

It’s not exactly polite discourse, but according to this critic, FAFSOLs are so wrong about providence that their whole conception of God is a figment of their own imagination: an idol, an idol worse than pagan idols. They look at evil events and declare God to be the author of them, the doer of evil. Seeing that this leads them into the bind of accusing God of evil, they try some doctrinal ju-jitsu by declaring everything good since everything’s done by God:

But they think that they have washed their hands clean when they reply, ‘We say that everything is good, since God has done it.” As if it were in their power to change black into white! That is how they acquit themselves when, after having called God a brigand, a lecher, and a thief, they add that there is no evil in any of that.

But that puts them in an intolerable bind: Either God does evil, or fibs when he says evil is bad:

But lo, hasn’t God Himself condemned murder, lechery, and stealing? Hence on this ground we should have to call God a liar in His Word in order to excuse Him in His works.

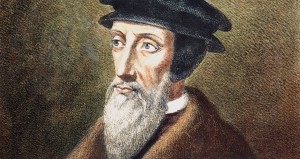

Enough of the FAFSOLs and their abstract providence! Nobody knows or cares about that particular group of sixteenth century radicals anymore, but I will give you the punchline by telling you who their opponent is: John Calvin. You were probably thinking Wesley or somebody. Yes, it is John “Mr. Providence and Predestination” Calvin who refutes their doctrine of abstract providence and accuses them of putting an idol in the place of God by applying the iron logic of fatalism to the living God. He does this in his book Against the Fantastic and Furious Sect of the Libertines Who are Called “Spirituals,” which he wrote in 1545. It has been published in english translation as Treatises against the Anabaptists and against the Libertines (edited by Benjamin Wirt Farley), and the chapter I quoted from is chapter 14, “On How We Ought to Understand the Providence of God by Which He Does Everything, and How the Libertines Confund It All When Speaking of It.”

Enough of the FAFSOLs and their abstract providence! Nobody knows or cares about that particular group of sixteenth century radicals anymore, but I will give you the punchline by telling you who their opponent is: John Calvin. You were probably thinking Wesley or somebody. Yes, it is John “Mr. Providence and Predestination” Calvin who refutes their doctrine of abstract providence and accuses them of putting an idol in the place of God by applying the iron logic of fatalism to the living God. He does this in his book Against the Fantastic and Furious Sect of the Libertines Who are Called “Spirituals,” which he wrote in 1545. It has been published in english translation as Treatises against the Anabaptists and against the Libertines (edited by Benjamin Wirt Farley), and the chapter I quoted from is chapter 14, “On How We Ought to Understand the Providence of God by Which He Does Everything, and How the Libertines Confund It All When Speaking of It.”

He of course goes on to teach the proper, biblical way of understanding providence, in a way that is in substantial agreement with his fuller and more satisfying handling of the doctrine in the Institutes. But it’s worth pausing to reflect on the fact that whatever Calvin teaches about providence –and I bet you it’s a pretty robust presentation, wouldn’t you think?– he apparently believes it positions him to condemn the abstract providence of the FAFSOLs.

Deconstructing abstract providence, even with Calvin’s help, is only a first step. It is a necessary act of exorcism to cast out the monstrous idol some people put in the place of the true God of providence. It’s a good thing to do. But it is not as good as establishing a solid, biblical doctrine of providence. That is a more important task for another day, but here is one rule to govern the way we think about providence: According to Calvin, we must think about providence in a way that is concrete, applied, and guided more by the Bible than by abstract axioms. The providence of the true Almighty does not render him the author of sin, and does not disregard or obliterate human agency.