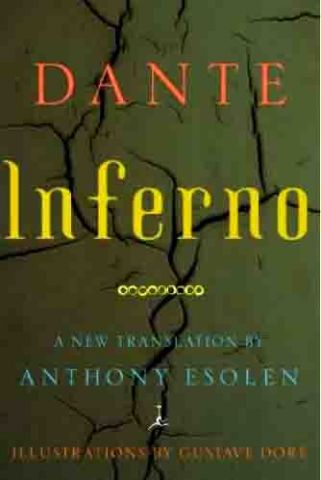

On Tuesday Feb. 25, Dr. Anthony Esolen spoke to the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University. Dr. Esolen, professor of English at Providence College, is best known for his translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Esolen’s edition prints the original medieval Italian verse on the left-hand pages, with his vigorous English translation on facing right-hand pages, daring you to compare its accuracy for yourself. Our great books program uses Esolen’s Dante, so we felt we were welcoming an old friend when we got to host his first visit to the West coast. A couple hundred students filed into the chapel where the lecture was held, many toting their marked-up Divine Comedies and eager to hear what The Master of Those Who Translate would have to say for himself.

On Tuesday Feb. 25, Dr. Anthony Esolen spoke to the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University. Dr. Esolen, professor of English at Providence College, is best known for his translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Esolen’s edition prints the original medieval Italian verse on the left-hand pages, with his vigorous English translation on facing right-hand pages, daring you to compare its accuracy for yourself. Our great books program uses Esolen’s Dante, so we felt we were welcoming an old friend when we got to host his first visit to the West coast. A couple hundred students filed into the chapel where the lecture was held, many toting their marked-up Divine Comedies and eager to hear what The Master of Those Who Translate would have to say for himself.

Dr. Esolen is a lively public speaker, displaying in person the same quick wit you would expect from reading his articles and editorials at Touchstone. His topic Monday night was “How to Put Your Soul on Ice: Freedom and Autonomy in the Divine Comedy.” In one sense, it was a talk as wide-ranging as it could possibly be: from the pit of hell to the height of heaven, with freewill, divine sovereignty, and creaturely contingency in between. But it was also carefully focused on a few motifs from the Divine Comedy, and most notably on the one image of Lucifer at the very bottom of the Inferno, stuck in a frozen lake of ice, chewing on the three arch-traitors of all history (Judas, Brutus, and Cassius), and flapping his enormous wings.

“Consider the flapping of those wings,” Dr. Esolen said, and proceeded to sketch out for us his own consideration of what Dante’s image reveals about sin. What grips the imagination more than the possibility of unassisted flight, of flying not in an airplane but with wings of our own, on our own power? But Lucifer’s wings, flapping back and forth perpetually, do not lift him from hell: they in fact are the fans that keep up the arctic blasts of air that keep the lake frozen forever. As in all of Dante’s Inferno, the essence of the sin is made manifest in the punishment. If Lucifer would cease to act upon his will to rise, to mount up into the heights on his own, the wind would stop, the ice would melt, and he would be free.

This is truly a telling detail in the Inferno, and Dr. Esolen developed his talk by showing all that is contained in the vision of hell focused on those flapping wings. Satan’s primal rebellion is the desire to be absolutely self-sufficient, to deny the message that inheres in all things: “We did not make ourselves.” According to Esolen, Satan is the father of lies precisely in this assertion of self-creation: “To assert that we made ourselves is to deny the contingency of our beings and to deny the web of relationships with which we entered into our beings, and without which we cease to exist.†With such a stake in autonomy, the satanic mind must necessarily undertake to destroy the law, any law, and become a law unto itself.

Esolen explored the surface contradictions and deep ironies of this sin. Surface contradiction: it simultaneously denies that there is a God, and asserts that it is itself God. Deep irony: in being a law unto itself, it becomes lawless, whereas if it would obey God it would be led to the high creaturely dignity of becoming truly a law to itself –a contingent law, but a real one. Like the planets, it would orbit its true center while spinning on its own axis.

From here, Esolen began making giant leaps of thought possible only for minds trained in Dante’s way of images (and not the kind of thing I could take good notes on). Up through the souls on the edge of hell, to the singing souls being ferried to purgatorial sanctification, and all the way to the God who alone possesses his existence not contingently, but necessarily. When Dante approaches this God (“greater than Aristotle’s first mover, because it doesn’t need anything to move; greater than Plotinus’ One, because it loves rather than just overflowing”), he glimpses a triune fellowship of eternal love, and the face of the incarnate Son. He strains to draw near to the mystery of the eternal Word: “But mine were not the wings for that flight,” Dante admits. So he does not flap his wings, but waits for God to condescend to him. Consider, then, the non-flapping of those wings.

From here, Esolen began making giant leaps of thought possible only for minds trained in Dante’s way of images (and not the kind of thing I could take good notes on). Up through the souls on the edge of hell, to the singing souls being ferried to purgatorial sanctification, and all the way to the God who alone possesses his existence not contingently, but necessarily. When Dante approaches this God (“greater than Aristotle’s first mover, because it doesn’t need anything to move; greater than Plotinus’ One, because it loves rather than just overflowing”), he glimpses a triune fellowship of eternal love, and the face of the incarnate Son. He strains to draw near to the mystery of the eternal Word: “But mine were not the wings for that flight,” Dante admits. So he does not flap his wings, but waits for God to condescend to him. Consider, then, the non-flapping of those wings.