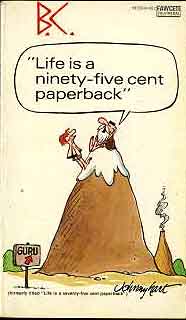

B.C. was one of my favorite comics when I was a kid. I didn’t read it in the daily paper, but in the affordable little paperbacks that came out regularly year after year.

I didn’t do a lot of caveman gags, but caveman gags were my favorite thing. What caveman gags I ever did, and sent to magazines, I never sold. To this date, I’ve never sold a caveman gag. So, one night I’m swaggering out of the art department at General Electric, the guys are going to work late, and I’m telling them, “You guys can stay here if you want, but I’m going home and create a nationally famous comic strip tonight.” I’m starting out the door and I think it was Bohanicki who says, “Why don’t you do one about cavemen? You can’t sell them anywhere else!” With those words Bohonicky became a minor prophet. (—from the long interview with Hart at Hogan’s Alley)

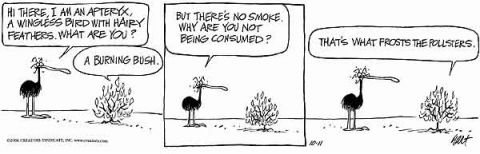

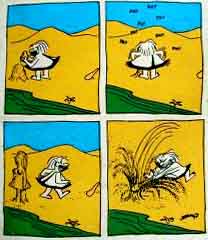

By the time Hart had burned through the entire repertoire of caveman jokes (cavemen hit women with clubs, are scared of fire, invent wheels, chase beasts, draw in caves, etc), he had managed to assemble a peculiar cast of characters and a new set of situational possibilities: a pedestal labeled “TRUTH” that characters could climb up and declaim from; a wise hermit on a mountaintop who gave advice to seekers; biped clams walking around on land; a whole society of ants that feared the tongue of the anteater (ZOT!); wandering dinosaurs who disrupted conversations (GRONK!); and my favorite: an apteryx who never uttered a word without first pronouncing a dictionary definition of himself:

As the strip assumed its mature style which it would maintain for decades, Hart’s bizarre wit also emerged. This Apteryx-Burning Bush strip has it all: Take one of Hart’s standard gags (self-defining Apteryx), add a religious reference (Burning Bush), and combine in sparse landscape. But who can account for the pseudo-hipster “frosts the pollsters,” which pushes the mildly comic situation into that surreal space that find the laugh?

The old B.C. paperbacks from the ’70s on are full of funny little touches like this, things that Hart handled perfectly. The caveman jokes never went away, and the fact that all the male characters had perpetual five-o’clock shadow was apparently the visual indicator that these urbane witticisms are not coming from fully civilized people. The differences between men and women are part of the stock-in-trade of caveman humor, and B.C. is no exception. It was a man’s strip from its initial planning, and the only two women are regrettably named “The Cute Chick” and “The Fat Broad.” You can just hear him thinking, “I need a cute chick for this joke to work,” and never getting beyond that.

Hart was a “one of the guys” cartoonist, and his work was generated by an around-the-water-cooler jokester network. He tells the story of the strip’s origin this way:

Anyway, I used to always love to have a beer, listen to the ballgame and draw. That was my modus operandus. I’m sitting there working on the strip and that little voice rang in my ear, “Why don’t you do it about cavemen?” So I thought, “This is great!” This warm, mischievous feeling came over me and I said, “What a good idea! A comic strip about cavemen!” … in everything thing I did, Simplicity was my byword. And it just fell right into place. What could be simpler than the beginning of man? The total simplicity. And then everything began to really mellow out and I sat there and began to sketch these funny little guys.

That “warm, mischievous feeling” wasn’t the beer: it was Hart’s peculiar muse for his whole career. Though he was a million miles from being a revolutionary, his creativity sought edges. He felt around intuitively for what you weren’t supposed to do, and he did it. “So they won’t buy my caveman jokes? Fine, I’ll make a whole daily strip about cavemen, that’ll show ’em!” The “Fat Broad and Cute Chick” coarseness came from the same spring, as some kind of intuitive revolt against feminism and politically correct speech codes. Hart phased out the tasteless names for the female characters sometime a few decades back; I’d like to think he did it because his growing Christian commitment led him to greater maturity on this front. Even for a joke, calling people “fat broads” is something you either grow out of, or you turn into Don Imus.

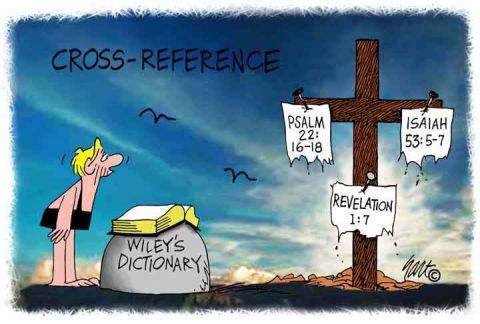

Even the most devotional and directly biblical strips —and there have been plenty in recent years— seem to have behind them a puckish glee at a chance to be the rebel. “So I can’t put Christianity into a comic strip, eh? Well, watch this!” Hart meant every word he wrote, but he also loved tweaking the nose of the syndicate, or at least the San Francisco Chronicle.

As Hart freely admitted, his Christian statements were not seamlessly integrated into the whole cartoon world he had created in B.C. They sometimes stood out from their backgrounds in distracting ways, like some kind of crucifixion scene in a Garfield strip. And some of Hart’s most evocative images, like the man throwing an inscribed tablet into the ocean and letting it float into the boundless ocean— worked better back when they didn’t meet with immediate, directly scriptural answers.

But Johnny Hart was a great cartoonist in the humble medium of the daily strip, and he put himself into his work in a way that made it impossible to keep Christian elements out of it. In that sense, the increasingly Christian profile of B.C. was an organic expression of the nature of the artist, who loved making mischief and increasingly loved the Bible:

Marschall: I don’t know if you have a lot of spare time, but do you read fiction? Do you have favorite authors?Favorite movies? Are you a movie buff?

Hart: I used to be a total movie buff. I’m out of that now. Whenever I have time to read, I read the Bible. Or I read books about the Bible, books explaining the Bible. There isn’t anything more interesting. Seeing the unbelievable things God is doing behind them. Moving and orchestrating and manipulating and fulfilling—it’s all just fascinating and exciting.