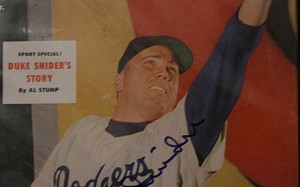

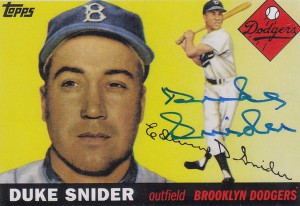

Baseball player Duke Snider died this weekend in Escondido, California, at age 84. If you’ve got baseball in your soul, the headline is all you need to read to know that his death symbolizes more than just a personal loss to his family and friends. The death of the Duke of Flatbush means something. It marks the passing of an era, as surely as the passing away of America’s last World War I veteran this same weekend.

Baseball player Duke Snider died this weekend in Escondido, California, at age 84. If you’ve got baseball in your soul, the headline is all you need to read to know that his death symbolizes more than just a personal loss to his family and friends. The death of the Duke of Flatbush means something. It marks the passing of an era, as surely as the passing away of America’s last World War I veteran this same weekend.

There are plenty of good sports documentaries out there about Snider’s significance in the history of baseball. Just search out stuff on the “Willie, Mickey, and the Duke” golden age of baseball, the 1955 World Series, and the Dodgers’ move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

For those of us who have never really felt that deep-down baseball emotion, the best way of understanding the public resonance of Duke Snider is that 1957 move to Los Angeles. Brooklyn’s public grief over the loss of their Dodgers has become emblematic of mid-century American disillusionment. Somewhere in the back of our minds, when we think about the American story, we follow a sub-conscious plot-line like this: America won the second world war, came home to what should have been a great 1950s, and instead sold our souls for creature comforts, commercialism, and better weather. That’s right: We moved to California.

Of course not everybody moved to California in the 1950s: The state census only (!) jumped from ten million to fifteen million during the decade, so it’s not like the rest of the country emptied out. But the attention of the nation turned Westward. Midwesterners headed for the sunny shores with an instinct that a personal Manifest Destiny had been left unfulfilled. California has always been about boosterism and self-promotion, and for a while in the middle of the twentieth century, the persistent rumor that there was a good life waiting out west filled a lot of American souls with the urge to get there. The gold rush of the 1850s got some sort of delayed kick-start, but this time with metaphorical gold. Everybody knew somebody who’d gone on pilgrimage, and leading cultural indicators all pointed that way. Lucy and Ricky moved to Los Angeles in 1955. And then in 1957 the Dodgers pulled up their deep roots in Brooklyn and went to Los Angeles, mainly for a better stadium. But also for the weather. And for the celebrities, and the girls, and the opportunity, and the publicity, and for all the other things people went to California for.

And then, for the Dodgers as for everybody else, California turned out to be just another place. It wasn’t the ultimate place, or the perfect place, or the place to end all places. It was just the western edge of a continent-long dream of getting there. The Dodgers went from being the mythological “boys of summer” to being just another franchise in just another sport. By now, they’ve been the Los Angeles Dodgers longer than they were ever the Brooklyn Dodgers, but their break-up with Brooklyn registered in the mythology of American heartsickness.

And then, for the Dodgers as for everybody else, California turned out to be just another place. It wasn’t the ultimate place, or the perfect place, or the place to end all places. It was just the western edge of a continent-long dream of getting there. The Dodgers went from being the mythological “boys of summer” to being just another franchise in just another sport. By now, they’ve been the Los Angeles Dodgers longer than they were ever the Brooklyn Dodgers, but their break-up with Brooklyn registered in the mythology of American heartsickness.

The Dodgers-to-Los-Angeles story, complete with Duke’s part in it, has been told many times as a New York story, most recently by Sam Anderson of New York Magazine. But my favorite version of it is the 2008 song by California singer-songwriter Terry Scott Taylor, “Broken Like Brooklyn,” from the Lost Dogs album The Lost Cabin and the Mystery Trees. Taylor has written dozens of songs that show him to be a Californian with deep roots in this rootless region, and he’s been reflecting on the Californian mythos with increasing intensity. His 1998 solo album John Wayne (named for the Orange County airport) was subtitled “Orange Grotesques,” for example, and his 2000 solo album was about the Avocado Faultline. But in the song “Broken Like Brooklyn,” Taylor set himself the task of thinking about his native California from a long way off: from the other side of the country. That makes the Dodgers’ move from the east coast to the west a perfect vehicle for his reflection on what “going to California” means to the nation.

In “Broken,” Terry, Mike Roe, and the other Lost Dogs sing from the point of view of a New Yorker who feels deep dislocation. California’s big with myth in this song: not only do rivers get lassoed as in tall tales, but the Rose Bowl gets filled with guacamole and invites not chip-dipping but skinny-dipping. And an east coast soul yearns for the golden land of California boosterism, where everything’s new and big and unsullied. Instead of deflating California hype from within, this song draws you in to the melancholy of the western dream and makes you feel the whole country’s midcentury complicity in it. Here are the lyrics:

Once I dreamed I was Ponce de Leon

and I’d grown so bitter and old

You whispered “Baby, I am Eureka

without any redwoods or gold”

So together we packed up the Airstream

with Pepsis, Pall Malls and Moon Pies

and we lassoed the San Joaquin River,

kicked back, went along for the rideI dreamed faith was our precious cargo,

determination our boat

We sailed straight on through troubled waters

and around the Cape of Good Hope

Then we dressed ourselves in fringed buckskins,

having leveled that brownstone of ours

Amid the Palos Colorados,

we slept ‘neath a blanket of starsWake up broken like Brooklyn,

the year The Bums left

in The Bronx on a cold day

while our Boys tan out WestNow we fly over junkyards and factories,

Dennys and transient hotels

above the churches and bars and video stores

the black smoke and slaughterhouse smells

Touching down in the golden Sierras,

we ate spinach quiches grown there

I wove a crown of boysenberries

through your lemon-scented hairBlonde girls in bikinis and snow skis,

in the desert, cashed in their chips

then filled the Rose Bowl with guacamole —

we took our clothes off and went for a dip

Bobbed and weaved like old Trolley-Dodgers

after reading a policeman his rights

Then we followed the Duke of Flatbush

and scaled the Boyle HeightsWoke up broken like Brooklyn

the year The Bums left

in The Bronx on a cold day

while our boys tan out west

Always broken like Brooklyn

after losing the best

Old sun-bleached bleachers at Ebbets

tore the hearts from our chests

It also manages to make listeners like me nostalgic for a New York baseball team I never cared about. It stretches the move from sea to shining sea, and back into the nineteenth century with the snide reference to “trolley dodgers.” In subsequent albums, Terry Taylor and the Lost Dogs have continued to work the American mythology for all its worth. They actually loaded up an Airstream with junk food and drove Route 66 from Chicago to the Santa Monica pier, writing music and staging concerts along the way, approaching California from a long way off and trying to figure out what it all means.

All of this is a long way from Duke Snider, who after all was not a real Brooklyn expatriate anyway: Snider was a California native, straight out of Compton. When he got mad at the fans and the press back in the 50s, he sneered that he only played baseball for the money, that Brooklyn didn’t deserve a winning team, and that he’d rather be back on his avocado farm in southern California. So when Snider died this weekend in California, he ended his days on native soil. According to the powerful mythology of California and her role in the American dream, we as a country lost our chance of ever really being where we belong, somewhere back in the middle of the twentieth century.