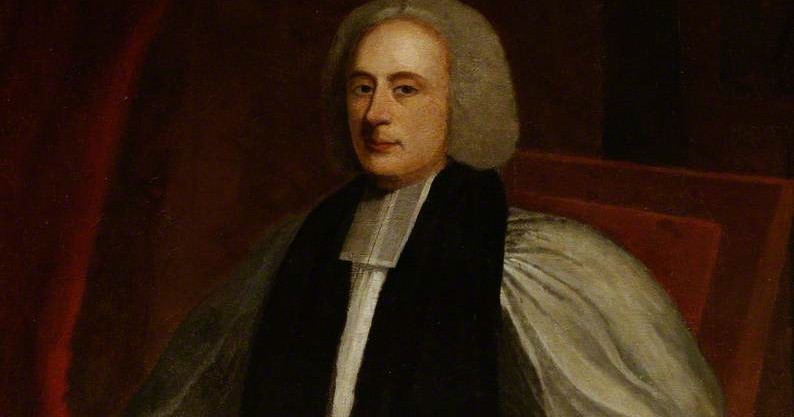

Joseph Butler (born this day, May 18, 1692; died in 1752) was the Bishop of Durham and a celebrated public intellectual.

Joseph Butler (born this day, May 18, 1692; died in 1752) was the Bishop of Durham and a celebrated public intellectual.

In fact, his greatest work, the Analogy of Religion (1736) was so famous in its own time and so influential for the next 150 years, that it is hard to explain how it could have dropped off of everybody’s reading lists so completely in the past century. It is one of the great curiosities of the great books canon. Butler’s Analogy didn’t just live out the normal lifespan of all those Darn Good Books that don’t quite make it into the perpetual Great Books canon. Butler’s book went from the top to the bottom in a remarkably short time. The people who published abridgments of the Analogy, who wrote commentaries on the Analogy, who cast the arguments of the Analogy into dialogue form for a more leisurely reading experience, and who referred to the great accomplishment of Bishop Butler, all talked about the Analogy as a book of lasting and permanent value. But who reads it now?

What was in the Analogy? It was a work of Christian apologetics, aimed at dismantling the popular skeptical deism of the intellectual class. Butler’s argument was based on an inherited body of scholarship which took as its axiom that the one true God was the author of the book of Scripture as well as the book of nature. But where earlier apologists had used this idea to argue directly for the reasonableness of the faith, or at least to assert that there could be no final conflict between faith and empirical reason, Butler’s main use of it was one step more nuanced. He was not struck so much by the guarantee of divine authorship behind the book of God’s words and the book of God’s works; he was more struck by how difficult both books are to read. He pointed out that natural scientists have to put up with a lot of ambiguity in their investigations, and have to make judgments based on probability as they ration the amount of their consent to the strength of the evidence. The full title of his work was “The Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed, to the Constitution and Course of Nature.” As Butler read that Constitution and Course of Nature, he saw it as a system filled with unpredictable puzzles and apparent incongruities. Good scientists keep open minds and are well aware that nature is likely to surprise them. The analogy Butler drew is that religion is just as surprising, and requires a similarly scientific mindset.

The argument itself, sketched out briefly, is still helpful today. I have used some version of it (which I think I swiped from C. S. Lewis) in establishing the plausibility of the doctrine of the Trinity. When people ask, “Why did God have to make it difficult with this weird Trinity stuff? Wouldn’t a unipersonal God be easier?” I reply that a made-up religion would of course be easier than a revealed one. But revealed truth has the same edge and texture to it that empirical truth has: You have to attend to its particularity rather than generalizing about how you think it ought to work out. And when speaking to non-theologians about the Trinity or the incarnation, I often find that scientists and engineers have less trouble approaching the subject than people in the humanities. The scientists are habituated to taking unexpected bits of information, even bits that seem contradictory, and giving them the status of data to be reckoned with: “Okay, he’s God and he’s man, that’s the data. Now let’s move on to how we should think about that.” Humanities people (I speak as one myself) are more susceptible to the temptation to suppress one side of the evidence in a premature attempt to smooth it out: “Well, he’s human, so whatever it means to call him divine, it can’t contradict that.”

John Polkinghorne, trained as a physicist and then ordained as an Anglican priest, has made much of this general approach in his books like The Faith of a Physicist. He often describes the sort of rationality we ought to expect of theology by analogy with empirical thought: “Significant scientific advances often begin with the illuminating simplicity of a basic insight … but they persist and persuade through the detailed and complex explanatory power of subsequent technical development.”

As for Butler, his Analogy of Religion developed the idea at great length, with considerable subtlety, and an open attitude to the scientific and philosophical thought of his day. Most people who try to account for the book’s precipitous fall from fame point to the revolution in scientific and religious sensibilities associated with the thought of Darwin. That has some plausibility, after all, for any book of Christian apologetics which suddenly stopped mattering to most people around 1890 (like Paley’s Evidences). But the parts of the book that I’ve read are not so strongly stated that they would have collided with Darwinism very directly. In fact, Butler rarely states anything directly: his style is famously circuitous and circumlocutive. His conspicuously erudite eighteenth-century style is certainly a contributing factor in his book’s decline in popularity. Some of Butler’s sentences are actually essays stretched out across two pages of semi-colons, dependent clauses depending on dependent clauses, and eight-point balanced parallelisms developed at length. But this was the kind of prose the educated classes of two centuries wanted in their English essayists, and there are good reasons to develop a taste for it to counteract the opposite tendency, in an age like ours that knows how to think about communication in terms of character limits (including the spaces between characters). Butler’s book encountered some other difficulties as it grew older, including the fact that it came to seem far too tame after the Great Awakening on the one hand and the increased skepticism of the enlightenment on the other. But as for its place on great books lists, the decline of Butler’s Analogy may be ultimately a matter of taste.