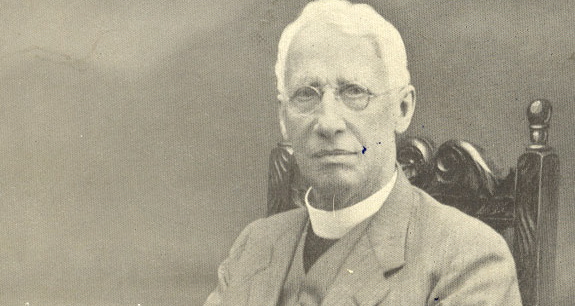

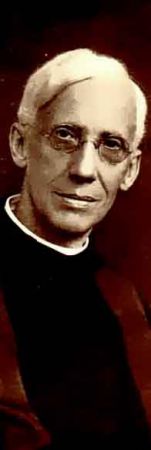

George Campbell Morgan (born 1863, died this day, May 16,1945) was an internationally renowned Bible teacher with an extensive ministry based at London’s Metropolitan Chapel. For about two years (from early 1927 to December 1928) he taught at BIOLA. Always a popular teacher, Morgan was well-liked at this young Bible Institute (just entering its third decade) in the fast-growing city of Los Angeles. Around graduation time in 1928, every student in residence was given a copy of his little book The Romance of the Bible. Putting Morgan’s book in the hands of every student was a clear signal that he and BIOLA were on the same page, and had teamed up for fruitful ministry.

George Campbell Morgan (born 1863, died this day, May 16,1945) was an internationally renowned Bible teacher with an extensive ministry based at London’s Metropolitan Chapel. For about two years (from early 1927 to December 1928) he taught at BIOLA. Always a popular teacher, Morgan was well-liked at this young Bible Institute (just entering its third decade) in the fast-growing city of Los Angeles. Around graduation time in 1928, every student in residence was given a copy of his little book The Romance of the Bible. Putting Morgan’s book in the hands of every student was a clear signal that he and BIOLA were on the same page, and had teamed up for fruitful ministry.

Nevertheless, in October of 1928 Morgan resigned from Biola in protest over an action taken by the board of directors. He moved on to a period of itinerant ministry elsewhere in the United States, before finally returning to London. What made this important Bible teacher leave a Bible Institute with whose spirit he was so fundamentally in agreement?

The answer lies in Morgan’s response to a major controversy, the largest in the school’s history. The story is long and tedious, centered on the controversial new dean, John Murdoch MacInnis, who wrote a confusing book which led to his firing, unfiring, and re-firing in a flurry of indecision. But for G. Campbell Morgan, the MacInnis controversy symbolized two things that required his departure.

First, it symbolized the division within the original fundamentalism of the turn of the century, between the kind of fundamentalists who wanted to do in the twentieth century what Dwight Moody had done in the nineteenth, and a more militant tribe of fundamentalists who were consolidating control over their institutions and developing a new strategy of separation. Whereas the original fundamentalists had separated from liberalism, the new fundamentalists were committed to avoiding contact with anybody who didn’t agree to separate from liberals, or –to take the logic of degrees of separation further– to separate from those who wouldn’t separate from those who wouldn’t separate from liberals. Morgan worried that a witch hunt against MacInnis meant reactionaries were gaining control, and the walls of that new fundamentalism were closing in on BIOLA. So he preferred to move on.

Second, and even more decisive for Morgan, was his personal friendship with MacInnis. When BIOLA’s administration would not support his close friend, Morgan considered it a point of honor to maintain his personal loyalty to MacInnis. Here are his own words from November 1928:

I have handed in my resignation from the Faculty of the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, to take effect on December 31st of this year.

My action has been caused by the fact that my friend, the Rev. John Murdoch MacInnis, D.D., Dean of the Institute, has placed his resignation in the hands of the Board.

The reason for his doing so is briefly as follows. Last year he published a book entitled Peter, the Fisherman Philosopher. This book has been charged with infidelity to the Evangelical Doctrines of our Faith; and a tendency to what is called ‘Modernism.’ Those appointed by the Board of the Institute to investigate this matter have declared that there is no trace of anything of the kind in the book, and have put on record their conviction that Dr. MacInnis is absolutely loyal to the fundamental things of the Faith.

Notwithstanding this fact, by a majority vote they have taken the position that because the attack has cast suspicion upon the Institute, it would be in the interest thereof that Dr. MacInnis’ resignation should be accepted.

Thus the Board virtually says: This man is not guilty, but because some people think he is he must be sacrificed in the supposed interests of an Institution.

Those who know me will know that I could not continue to work in relation with a Board capable of such an unjust and cruel practice of expediency.

I return, therefore, to my work on independent lines, as I did before coming to Los Angeles.

G. Campbell Morgan.

The MacInnis controversy was complex, and Morgan’s description of the actions taken by the board (which included Charles Fuller) is one-sided. Nevertheless, he was right about both of his major concerns: A handful of ultra-conservative agitators really were causing unnecessary trouble in already turbulent times (some of MacInnis’ main accusers were dismissed by the board, partly for their instransigence and partly for insubordination and unprincipled behavior). And of course he was right to take a stand on the side of a long-time friend whose integrity he respected, over the vacillations of a board of directors who had not yet earned his full trust.

For anybody with an interest in Biola’s heritage, the departure of G. Campbell Morgan in 1928 was a minor tragedy, and one of the worst casualties of the MacInnis controversy. Morgan was a great Bible teacher with an international reputation and considerable influence. His ministry was perfectly in line with the Bible Institute’s goals and direction, and when he came to BIOLA in 1927 he gave every indication that he might be here to stay. Had he remained in Los Angeles instead of returning (eventually) to London, the synergy of Morgan and BIOLA would have been a great force for good.

Even with his short stay at the Bible Institute, he is high on the list of the most important people ever to teach at BIOLA. It was in recognition of his stature and his alignment with the school’s fundamental mission that we named the Torrey Honors Institute’s annual theology conference after him, and more importantly that we have made him the namesake of one of the two houses in the honors program, placing more than half of our students under the symbol of his legacy in the Morgan House.