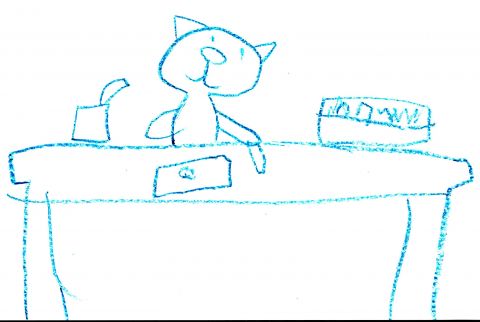

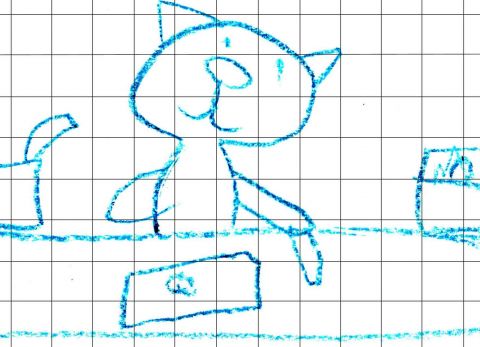

This image is constructed very carefully on a grid of horizontals and verticals, and it is the table that does most of the work in establishing the grid: strong vertical legs, strong horizontal tabletop. The crayon box picks up the architectural cue and stands like a block of buildings. The juice box does the same, though its little flexy straw is allowed a rakish tilt or curvilinear bow. Both boxes hover just above the line of the tabletop, an impossibility of physics which can only be justified by the needs of the composition: by hovering over the table, they deliver the precious cargo of parallel line segments very close together. Close-together parallels are compositional gold, because they tell the eye authoritatively that the horizontal line means what it says: they underline it. The cat sits bolt upright, but his head leaps out of the grid with an expressiveness that provides the emotional center of the piece.

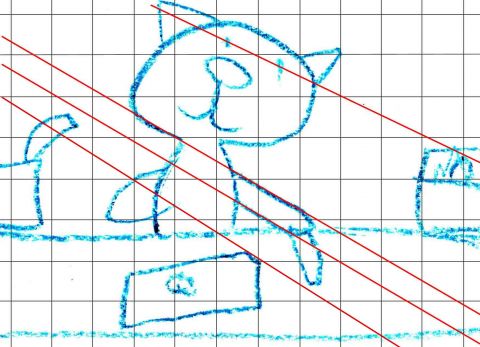

But the coup de grâce (which is French for “cup of goose liver”) is the pair of dots that make the cat’s eyes. Never mind that the one on the viewer’s right has a downward smudge which teases us with its hint of true verticality. Those eyes are points on a line which cuts a bold diagonal across the grid. That line puts all the power into the image, so the artist brings all his compositional tricks in service to that line. He uses the cat’s drawing arm (the cat, by the way, is left-handed, but I have it on good authority that the boy is right-handed) to define another set of close-together parallels, which underline at a distance the bold diagonal of the implied eye-line. See the relationships here:

The three red diagonals stand in an obvious structural relationship to each other, and by rendering them explicit against the grid I have done nothing but articulate the composition’s latent forces.

No doubt some readers are growing skeptical at this point. Could any artist, especially a six-year-old using crayons, possibly be composing at this level of intentionality? I present two pieces of evidence and a final thematic observation.

One. Attend, for one moment, to the fourth and lowest of the diagonal lines I have drawn. It picks up the strangely lopped-off corner of the drawing-within-the-drawing. Yes, the corner of the drawing is missing. It is simply not there, and that requires explanation. Into the center of a composition which depends on a tacit grid and derives its power from controlled deviations from the grid, the artist places a rectangular page inside a rectangular table. But then he lops one triangular corner off of that central rectangle. Why is the corner of the sub-drawing missing? I will listen to no interpretation of this composition which fails to reckon with the missing triangle from the drawing within the drawing. Its absence demands at least one red diagonal.

Two. Does the argument for descending diagonals seem arbitrary? Could I have found meaningful relationships no matter what lines of composition I had chosen? I think not. Here, for example, are the most relevant rising diagonals in the piece:

I defy anyone to make compositional sense of that hodge-podge of linear forces. They are background noise, a rioting chaos of angles signifying nothing. Their random distribution only makes it clearer that the opposing diagonals are the bearers of significance in the total composition. There is nothing in there except –hey, on the left there, isn’t that Mary Magdal– oh, never mind, my mistake. Nothing to see here, and that’s the point of the green lines.

And finally, a thematic interpretation, one which finally transcends the merely compositional considerations. All great art is ultimately art about art, and whenever an artist makes a drawing of an artist making a drawing, those who have eyes to see will surely see. What leaps out of the compositional grid is most decisively the head of the artist, but it is underlined by his equally un-gridded drawing arm, his crayon, and the page on which he draws. It is tempting to incorporate the otherwise inexplicable curve of the straw into the same inward-spiralling movement, but I am trying not to get carried away.

After all, it’s just a kid’s drawing.