This is an article that appeared in the Christmas Day edition of the Orange County Register back in 2001. It was written by award-winning religion reporter Carol McGraw (now of the Colorado Springs Gazette) and featured a large illustration by the Register’s staff illustrator Lisa Mertins. It was a fun Christmas morning piece, and is now long gone from their online archive. I’m re-posting it here because I was the main scholar who was interviewed and quoted for the piece. The article doesn’t exactly capture what I’d say about Christian imagery if I were writing out my main ideas about it, and a couple of points got simplified to the point of garble. But for a short, easy introductory piece in the Christmas morning paper, I was pleased to be a resource.

Christian faith: Picture it

Many symbols that were once secret signals for followers are a mystery for modern believers

December 25, 2001

Story by CAROL MCGRAW

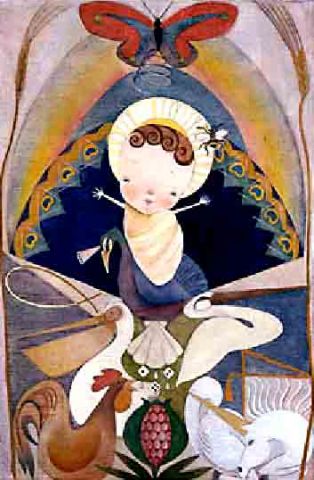

Illustration by LISA MERTINS

The Orange County Register

Which of the following are symbols of Christianity?

A. Peacock

B. Cross

C. Daisy

D. All of the above.

The obvious answer, of course, is B. The cross. It represents the crucifixion of Jesus, whose birth is celebrated on Christmas and whose death and resurrection Christians believe make salvation possible.

But the peacock, daisy, triangle, stork, iris and other figures seen here are Christian symbols, too.

The origin and meaning behind images seen in old paintings, prayer books and etched church windows are lost to most modern believers, says Fred Sanders, assistant professor of theology at Biola University in La Mirada. His specialty is deciphering trinity symbolism in religious art.

“A person really has to know his Bible and Christian history to decipher a lot of these old symbols. We walk in some old cathedrals and don’t have a clue. It’s a baffling symbol system, like looking at Hindu iconography.”

More than church art, symbols were once secret signals for martyrs who wanted to recognize fellow Christians. Symbols were also “books for the poor,” he points out. Pope Gregory the Great promoted their use in the sixth century as visual cues to stories that evoke spiritual emotion.

Religious symbols, which often represent the unseen or unknowable, have been around since Christ’s death about 2,000 years ago. One of the earliest, the fish, was a symbol used on signet rings by Christians in Alexandria in the second century.

Nativity scenes, too, are rich with symbolism. The omnipresent ox and ass harken not to Gospel accounts of the event but the Old Testament in Isaiah 1:3: “The ox will know his owner, and the ass, his master’s crib.” Origen, a third-century theologian, first drew on that passage to connect the animals to Jesus’ birth, Sanders says, and artists picked up on it.

Saints also could be recognized by the symbols that surround them. Early Christians readily recognized St. Apollonia in a painting if she carried a pair of pincers with a tooth. Her props represent how tormenters pulled out her teeth when she refused to renounce her faith.

And the saint with a rock on his head? That’s St. Stephen, who died by stoning.

Symbolism sometimes is divisive. Catholics and Orthodox churches use images and icons, but some Protestants eschew any representational art in a religious space. “It is not considered appropriate because they believe it looks like idolatry,” Sanders explains. Some churches today don’t even put up a cross inside or outside the sanctuary. “They go undercover. It’s a way to attract the unchurched who sometimes feel uncomfortable with such trappings.”

Until the Renaissance in 1300 A.D. symbolic art was created anonymously. These days image handling has become professionalized. “If you are a church and want a Christian symbol for your congregation, you hire an ad agency,” Sanders says. He points to the Methodist logo – a cross with a river of fire coming from it – as an example of a successful modern symbol.

The most intriguing symbol may be the face of Jesus. It’s symbolic because no one knows what he really looked like. He has Asian features in India and China, and in the West he’s often depicted as “a white guy with blond hair.”

In recent years, more artists have given him Jewish features, as per his origins. No matter, Sanders says. Everyone recognizes him in art. “There is always a spiritual continuity in his face that is recognizable.”

Symbols: what they mean

Bee: Resurrection. Honey thought to be food of immortality.

Butterfly: Like pupa to butterfly, Christ’s followers born to new life.

Daisy: Holy Child’s innocence.

Dice: Roman soldiers cast lots at foot of cross.

Fish: Ichthys in Greek. Letters stand for Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter. Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Saviour.

Halo: Early Jewish sign of spiritual light. In medieval times, a saint with a rock on his head, holding a book and wearing a halo, represented St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr who was stoned. Other saints were painted with hatchets in heads, another sign of martyrdom, since many were beheaded.

Peacock: Resurrection. Birds once thought to have incorruptible flesh. After molting, feathers were more beautiful than ever.

Pelican: Nourishes its young with its own blood by piercing its side. Like atonement, Jesus and Eucharist.

Pomegranate: Christ’s power. Seeds break the hard shell; Jesus burst from tomb.

Rainbow: Ark is the church, the rainbow, deliverance.

Rooster: Apostle Peter’s betrayal. In scriptures, Jesus said, “You will betray me three times before the cock crows.”

Rye grass: Sown by the devil with wheat, but separated at harvest as are the wicked separated from the good.

Shell: With drops of water, baptism.

Spiral: Liturgical year, which repeats cycles of Christ’s death and rebirth, and each time offers salvation to believers.

Stork: Announces spring, new life. Like angel’s Annunciation to Mary of virgin birth.

Triangle: All-seeing eye of God looks out from the Trinity (God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit).

Unicorn: Jesus, purity and virgin birth.