An earlier generation asked What Would Jesus Do? But these days, people are increasingly comfortable with skipping the hypothetical, shifting out of the subjunctive, and just telling us What Jesus Would Say, in their opinions. If he were really here, that is: if he were talking, if he were blogging, or meme-ing, or cartooning, or writing devotionals.

What seems new in all of these media is that this Jesus, or rather these diverse Jesuses, these Jesi, speak for themselves, in the first person.

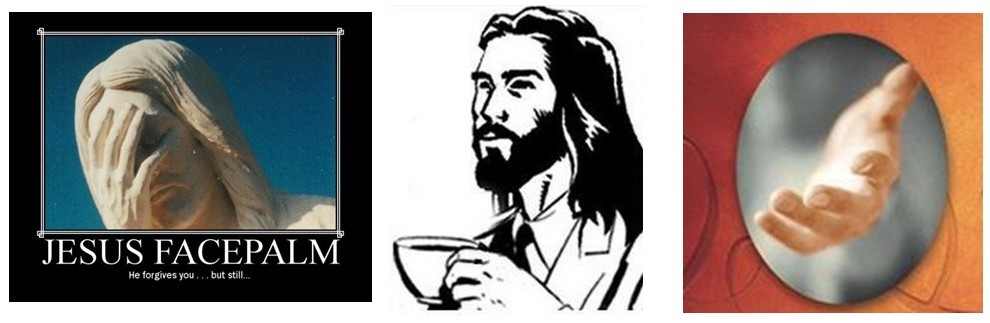

Boutique Jesi have begun popping up in various media. In the medium of internet memes, there is facepalm Jesus:

The gesture, intended by the original artists as sorrow but re-interpreted by our sarcastic eyes as comic exasperation, is eloquent in itself. But the superimposed words let you know what he’s thinking: “Oh brother,” or “for me’s sake.” It’s impossible to deploy one of these images with any reverence; the irreverence is the frisson of putting words in the mouth of Jesus. Posting one of these implies that you know the answer to the strange new question, What Would Jesus Facepalm? (I’ve seen him facepalming dorky tablet photographers, which I take personally, okay?)

Internal evidence suggests that Facepalm Jesus is propagated by non-Christians of the “Lord, save me from your followers” variety, but I have no doubt that Christians also use them after applying the universal prophylactic of irony: “I’m not making fun of Jesus, I’m making fun of what people think about Jesus.” Irony is actually not as effective a prophylactic against irreverence as young people think; it just hardens the heart in a different way.

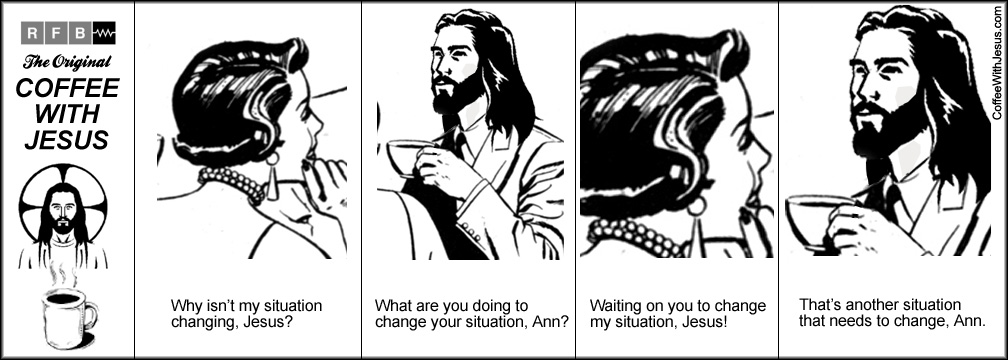

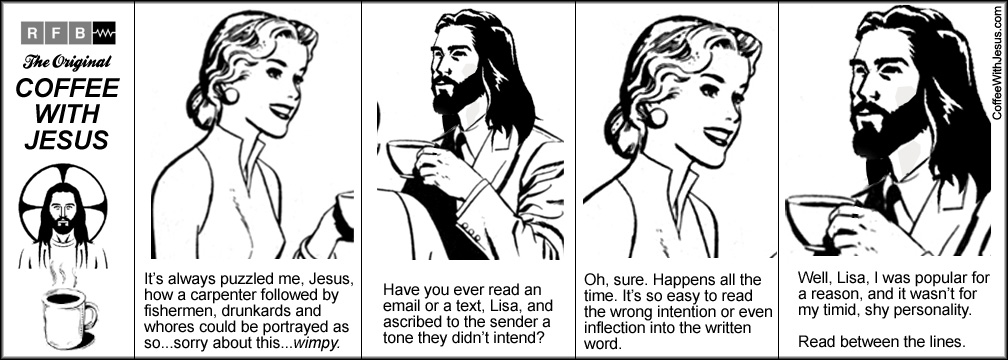

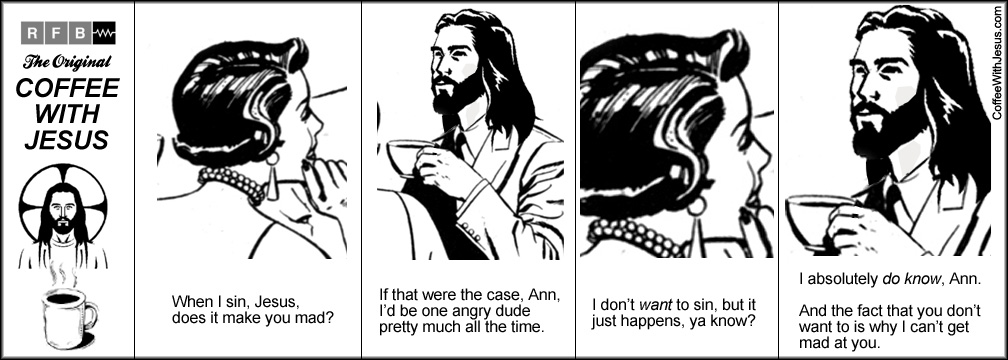

Far, far better than the anonymous hive-mind’s Facepalm Jesus (faint praise, I admit) is Coffee With Jesus, the clip-art online comic strip written by David Wilkie. It’s a website, it’s all over your Facebook wall if you’ve got that sort of friends, and now it’s an IVP book. Here’s a typical entry:

and another:

The basic joke, beyond the campiness of clip art, is that Jesus is sassy and gets to deliver all the good punch lines. Wilkie gives him the last panel and the best zingers. But in the dynamics of a four-panel strip, that also means Clip-Art Jesus is always reactive, responding to the set-ups that the other characters provide him (especially in panels 1 and 3). That reactive quality is symptomatic of the whole Coffee with Jesus project, which is at its satiric best when it’s puncturing somebody else’s ideas about Jesus –characters like clip-art Carl really are charmingly clueless– and at its creepy worst when it gives cartoon Jesus a few lines to present himself as he really is.

Wilkie generated Clip-Art Jesus as a way to mock inferior Jesi, and is clearly concerned, in his own way, to present a believable, lovable, real Jesus to his readers. This intent comes across in the book, but also in the deletion of some strips from the website’s archive, where he says “some of the cruder, earlier ones we’ve removed as they seem to have given license to mockers and imitators who’ve abused this concept.” This is a far cry from Facepalm Jesus: comic strips can do more than memes can, and Wilkie is not only a good script writer but a person intent on actual ministry. But in spite of the more complex medium and the more skilled writer, some of the same limitations apply to the basic, underlying decision, which is to compose new dialogue for the character Jesus as a way of broadcasting your criticisms. And then when coffee Jesus gets the mic, he’s only interested in a fairly limited circle of things. Mainly, he wants special, relationship-building coffee time with you. The main theology he is pushing is a theology of quiet times, of daily devotions, of remembering that Jesus is in charge and keeping your eyes open for where he is at work in your life. Jesus with coffee understands you, and says so:

I’m not sure where to start with that one; panels 2, 3, & 4 won’t bear the pressure of very much theological analysis. But notice that they are all determined in advance by the opening gambit, which is the question about how Jesus Christ feels, emotionally-relationally, about Ann.

That opening question reflects the main thing going on in Coffee With Jesus. It’s a pang of hunger for a deep, personal encounter with Jesus, a desire to know what Jesus thinks of us, feels about us.

A few years ago I met Neil Saavedra, who does a Los Angeles radio talk show called the Jesus Christ Show. He takes calls and gives advice in character as Jesus Christ. I had dinner with Neil and found him to be a likeable guy and an altogether reasonable person, with good performer’s instincts, no delusions of messiah-ship, and a desire to help people. Furthermore, the answers that he, as Jesus, gives on the radio generally sound like the kind of thing Jesus would say, for the very good reason that they often are what Jesus in fact said: Saavedra uses Scripture constantly in the answers he gives. Laugh it off as something that could only happen in Los Angeles if you want, but there it is again: an artist who gives us Jesus in the first person, and an audience who wants it. All in all, talking with Neil I had to admit that this guy was doing pretty much the best job I could imagine anybody doing in carrying out a terrible, terrible idea.

Because it really is a terrible idea; all of it from Meme Jesus to Coffee With Jesus, call-in Jesus, and beyond. Whatever good can be done with these instruments is more than counterbalanced by the mental pollution of a climate in which the Jesi of various media are acting as spokesmen for their authors’ insights. And even if the “Jesus with new word balloons” phenomenon springs from a heartfelt desire to hear from Jesus today (a motivation that I think should be treated tenderly, given some respect, and encouraged), the device of a talking Jesus character saying your own words is self-defeating. That character can only say things you already know. From such a character you can only learn what the finite, limited, contemporary author has put into his mouth. Translated to the Vaudeville medium, it’s spiritual ventriloquism with a Jesus dummy. (And if you think literal “ventriloquism with a Jesus dummy” is tasteless or a bad idea, it’s worth your time to make your reasons explicit, because the puppets already exist. They await only a ready audience.)

Time would fail us if we talked about all the down-market merchandise that puts new words from God or Jesus on your coffee mug, your t-shirt, your billboard. Think about it: we live in an age when people think it is amusing, or poignant, or incisive, or something, to have billboards with quotations from God on them. Not actual quotations, but new ones like “‘keep taking my name in vain and I’ll make rush hour longer,’ signed God,” or “‘I miss when you used to say ‘Merry Christmas,’ signed Jesus.” Something has clicked in the collective unconscious, and this trope is bubbling out in every medium imaginable. Why does Jesus suddenly seem to have so much to say that he had not said before?

Time would fail us if we talked about all the down-market merchandise that puts new words from God or Jesus on your coffee mug, your t-shirt, your billboard. Think about it: we live in an age when people think it is amusing, or poignant, or incisive, or something, to have billboards with quotations from God on them. Not actual quotations, but new ones like “‘keep taking my name in vain and I’ll make rush hour longer,’ signed God,” or “‘I miss when you used to say ‘Merry Christmas,’ signed Jesus.” Something has clicked in the collective unconscious, and this trope is bubbling out in every medium imaginable. Why does Jesus suddenly seem to have so much to say that he had not said before?

Of course the ten-ton gorilla in the first-person Jesus contest is Jesus Calling: Enjoying Peace in his Presence, Sarah Young’s devotional book that has sold ten million copies in ten years. This book has quietly made its way into all sorts of places in the past decade; read about it and its author in the New York Times). If Coffee With Jesus was a quantum leap beyond Facepalm Jesus, then Jesus Calling is another qualitative jump forward. Young is not engaged in satire, but is giving actual spiritual guidance; and she is not on the radio, but in the well-respected medium of devotional book. But just like the memer, the cartoonist, and the DJ, she gives her guidance from the perspective of Jesus, in his voice, first-person. Here are some of the things the Jesus Calling Jesus says:

As you focus your thoughts on Me, be aware that I am fully attentive to you. I see you with a steady eye, because My attention span is infinite. I know and understand you completely.

This sacrifice of time pleases Me and strengthens you.

I want you to learn a new habit. Try saying, “I trust you, Jesus.” …Your continual assertion of trusting Me will strengthen our relationship.

Each failure is followed by a growth spurt.

It’s all right to be human.

Whisper My Name in loving contentment.

Listen to the love song that I am continually singing to you. I take great delight in you.

Don’t take yourself so seriously. Lighten up and laugh with me.

Trust Me enough to accept the full forgiveness that I offer you continually. This great gift, which cost Me My Life, is yours for all eternity. Forgiveness is at the very core of My abiding Presence.

The world is too much with you, My child. Your mind leaps from problem to problem.

Ignore, for a moment, everything else that’s going on in these statements and consider them first of all literarily. If you compare the character named Jesus in the canonical gospels to the character named Jesus in Jesus Calling, you can see right away that they are different literary characters. The character named Jesus in the New Testament not only didn’t say “lighten up and laugh with me;” he in fact couldn’t say it. If that line appeared in any of the gospels, the reader would be jarred by the sudden transition.

Young is of course intentional in not giving us the Jesus of the gospels, but the Jesus of the quiet time, the daily devotion. She wrote this devotional as an exercise in listening to what Jesus is saying to her here and now, in times of spiritual listening. These utterances make perfect sense if you view them as the high end of a continuum with Facepalm, Coffee, and DJ Jesus. But you may think they belong on another continuum, either as a kind of prophetic utterance, a charismatic “word” to be shared in the congregation (of the “I believe the Lord would say” variety), or as a kind of channeling.

I bet it wouldn’t take much digging to find, among older spiritual writers, a lot of words composed and presented in the first person as Jesus talking. I have a vague recollection that I’ve seen scattered instances of it in Sibbes and Goodwin, and I know it’s in a long stretch of The Imitation of Christ and Bernard of Clairvaux. So in that sense, Jesus Calling is not radically novel, and there is a diffuse sort of precedent for this approach. But not until our generation has it been carried out so consistently, received so eagerly, or presented in isolation as a stand-alone product.

As for the content of Jesus Calling, the criticisms are obvious enough, and are exactly the kind of thing you would expect if you tried to write new words for Jesus (a writer less disciplined than Young would do considerably worse with a concept so utterly foredoomed to disaster).

*Jesus sometimes sounds like a therapist, sometimes like an Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor, sometimes like the perfect boyfriend.

*Jesus is concerned to teach you how to use a set of techniques which include speaking positive affirmations (“Try saying, “I trust you, Jesus.” …Your continual assertion of trusting Me will strengthen our relationship.”), attending to the vicissitudes of spiritual experience (“each failure is followed by a growth spurt”), and focused meditation. More telling than the particular techniques is the technical focus itself: this Jesus is leading a clinic on How To Commune.

*He makes a few basic, common, and mostly harmless exegetical blunders, such as taking Psalm 46:10 (“Be still, and know that I am God“) out of context as a reference to quiet times.

*The scope of his interests is very, very narrow, and he circles back to a small number of topics repeatedly. The book’s sub-title, “Enjoying Peace in His Presence” perfectly summarizes the boundaries of the message.

*He calls you “my child” constantly, a pattern of speech not characteristic of the canonical Jesus. Though the canonical Jesus does occupy a fatherly office toward believers in some regard (I’d love to say more about this later), he is overwhelmingly concerned to be the one who connects you to God the Father. Constantly calling believers “my child” is getting off message. Jesus Calling has first-person problem, but it’s not about the first grammatical person (“I, Jesus”); it’s about the first trinitarian person, the forgotten Father.

*As a result, the Jesus of Jesus Calling has a weak trinitarian theology. The word “Father” appears 57 times in the Kindle edition, but more than 50 of those occurrences are in the Scripture quotations that are printed after the new words from Jesus (no surprise that the Bible passages have a better theology than the new prose). When he has the mic, the Jesus of Jesus Calling rarely mentions his Father. The Holy Spirit fares a little better (he is the one who “guides your thoughts” to Jesus), but overall this book is a perfect example of a sub-trinitarian variety of Jesus-piety that is Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring.

A lot of good people are reading Jesus Calling, and are probably not being harmed by it. Readers are often protected because they bring their own more robust theologies along with them and presuppose them as they read. In fact, I bet Sarah Young has a better theology than the theology that the terrible concept of Jesus Calling is able to communicate. I bet I’d enjoy talking with Sarah Young about all kinds of Christian things.

What I’m sure of is that I’d rather talk with her than with the eponymous main character of Jesus Calling, whose literary presence I do not enjoy. I do not want coffee with him. In meme terms, I facepalm the whole idea. Epic fail, as the kids say.