The sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation in Spain continues to be a neglected subject, but one that immediately repays any attention you give it. You might say that to this day, “No one expects the Spanish Reformation!” In fact, when we think of the sixteenth century in Spain, we are more likely to think of the Inquisition. But of course the Inquisition had to have something to Inquisit, right? And that’s where the story starts.

The sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation in Spain continues to be a neglected subject, but one that immediately repays any attention you give it. You might say that to this day, “No one expects the Spanish Reformation!” In fact, when we think of the sixteenth century in Spain, we are more likely to think of the Inquisition. But of course the Inquisition had to have something to Inquisit, right? And that’s where the story starts.

Consider the case of Constantino Ponce de la Fuente (1502-1559). Witty, erudite, and profound, Constantino was a popular preacher in the massive Cathedral of Seville and in the court of Emperor Charles V. He wrote works in systematic theology (Suma de la Doctrina Cristiana in 1543, Doctrina Cristiana in 1548) and also a children’s catechism. But his most famous work is the Confession of a Sinner (1547).

Constantino’s works are wonderfully available at the Post-Reformation Digital Library, where he is listed as writing in the Roman Catholic tradition. That’s as correct as can be, I suppose. Constantino certainly preached and published within the established Roman church of his time in Spain, with official approval and to great acclaim. But the content of his teaching kept pushing issues that we have to identify as Protestant: justification by faith is a leading theme, and he repeatedly championed the authority of Scripture over tradition. Late in his career, he did run afoul of the Jesuits and the Inquisition, and while he wasn’t exactly executed, he did die in prison and has long been counted among the martyrs of the Reformation. Carlos Eire calls Constantino “the very embodiment of the complex history of Spanish Erasmianism and religious dissent.”

Few of his works are available in English, but the 1547 Confession of a Sinner has been translated, and has achieved classic status (click link for a pdf of the public domain 19th-c translation).

Constantino’s Confession is written in the form of a prayer to Christ, and one of the most striking things about it is the way it presupposes the grand, objective truths of the Christian faith and then drives toward personal application. The centerpiece of the Confession is the Christian creed turned into personal prayer, as Constantino rehearses the truths of Christian doctrine by praying them to Jesus and applying them to his own situation. A sample from the second article:

Being Creator and Upholder of the world, with Thy Father, in the unity of one essence, and of one God ; knowing how abused by me Thy first gift, committed to my hands, had been, Thou, Lord, hast assumed a new office in relation to myself, that of being my Saviour and my King; to deliver me from all the dangers and disasters to which I had exposed myself, and to be ever henceforth my Captain and my Defender, in order that I might not relapse into them. I, like a simpleton, ignoring my own sins and ignoring Thy mercy, have neither looked upon myself as lost in the fall, nor have I acknowledged Thy gracious favours, I have neither gained experience from my first fall, nor have I taken precautions against future falls.

You can hear in this prayer the gears of objective truth engaging the gears of subjective experience, as Constantino (and, I would hazard, the rest of the Spanish Reformers) labored toward a spiritual renewal of the Spanish church from within. It was a renewal would have reformed that church if it had been politically possible.

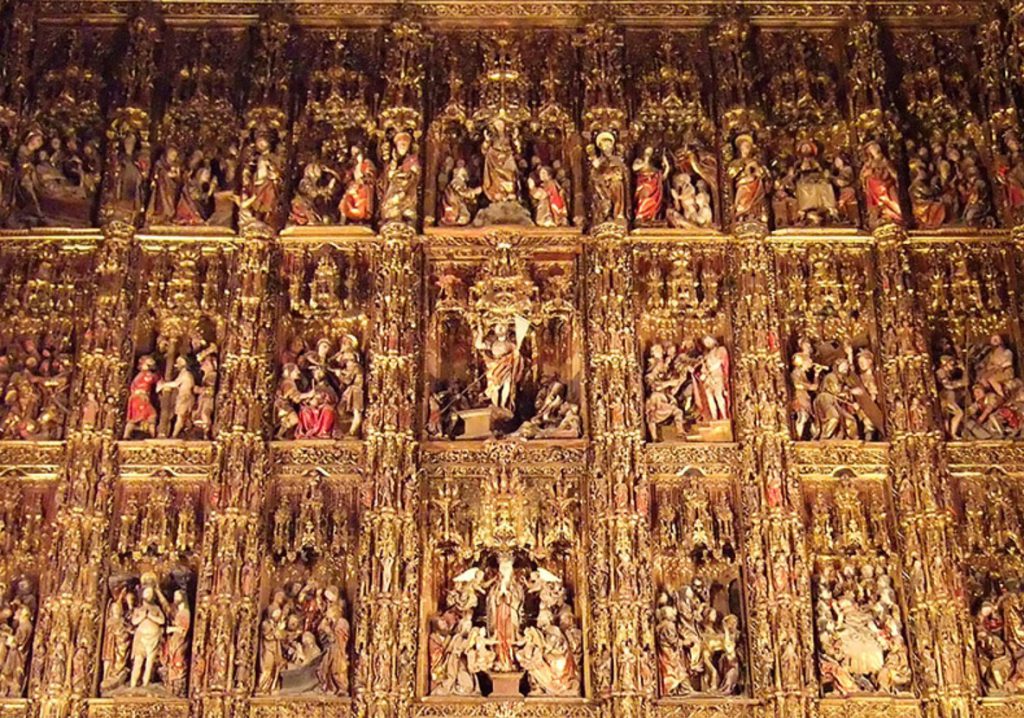

Constantino’s literary style, as glimpsed in English translation, is evidently florid and expressive. Though he is highly educated, he is not afraid of pouring out his heart profusely and directly. His refined poetic sensibilities tend in the direction of effusiveness and even baroque gorgeousness. He speaks like this: “Since Thou art Sanctification and Beauty, here is the turpitude and the hideousness of the works of the devil; remove them, Lord, and it will be manifest who Thou art.” You can picture him saying these words from the pulipit in the Seville Cathedral with its astonishingly ornate retablo looming behind him (see picture above; this retablo was begun before the time of Constantino).

The Confession is only about 50 short pages in length; give it a read! And if you’re in the Biola area and motivated to discuss such things, get in touch with me or with Dr. Octavio Esqueda. Using the attached pdf, we’ll be discussing Constantino’s Confession in early December as part of our ongoing Spanish Reformation Reading Group, which previously discussed Juan de Valdes.