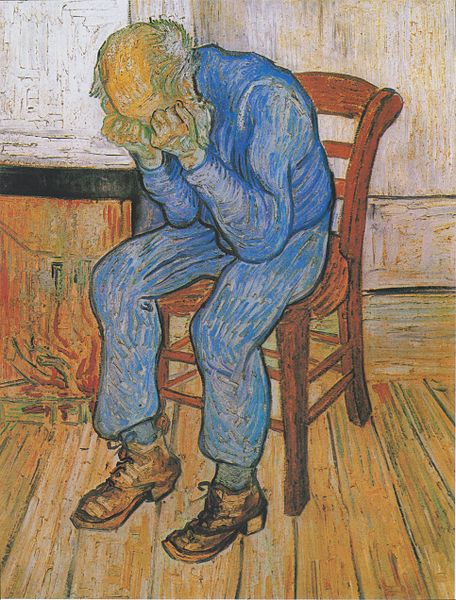

During my graduate school years, I was fortunate to have worked on the pastoral staff at three different churches. They were all great experiences with different challenges and expectations. One element that was common to each position, however, was the need to engage at times in some form of pastoral counseling, bringing  consolation to those who were hurting or questioning. It is truly amazing the amount of “stuff” that people are dealing with — grief, depression, habitual sin, family/marital strife, uncertainty about the future, etc. The need to talk with people transcends all categories of race, gender, age and station in life. Many of these moments of counseling were difficult for me and not only because I always didn’t have THE answer. Instead, there were moments when I questioned the effectiveness of my counsel. The words and scriptural promises that I used during these times of counseling did not lack truthfulness, rather, they oftentimes sounded too simplistic or, perhaps, even trite. Now it is true that God’s Word is often simplistic in its wisdom but when counseling someone simplicity (whether real or perceived) is not desirable, making the task of pastoral counseling difficult and challenging — not to be entered into lightly.

consolation to those who were hurting or questioning. It is truly amazing the amount of “stuff” that people are dealing with — grief, depression, habitual sin, family/marital strife, uncertainty about the future, etc. The need to talk with people transcends all categories of race, gender, age and station in life. Many of these moments of counseling were difficult for me and not only because I always didn’t have THE answer. Instead, there were moments when I questioned the effectiveness of my counsel. The words and scriptural promises that I used during these times of counseling did not lack truthfulness, rather, they oftentimes sounded too simplistic or, perhaps, even trite. Now it is true that God’s Word is often simplistic in its wisdom but when counseling someone simplicity (whether real or perceived) is not desirable, making the task of pastoral counseling difficult and challenging — not to be entered into lightly.

The great medieval philosopher/theologian Boethius, on the other hand, seems to have another way of engaging in counseling and consolation, by invoking Lady Philosophy herself. Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy is an amazing work that yields fruit after each reading. In the text, we discover that Boethius is wrongly imprisoned. Though he has striven to cultivate a life of faithfulness (both to God and the state) as he understands it, he still finds himself sitting alone in a prison cell while the joyous exaltations of the “free” float through his window and into his ears. Boethius’ problem, as he sees it, is not only that he too would like to enjoy playing freely in the streets, eating figs and drinking good wine but rather that he believes that the good are being punished while evil people are being rewarded. He’s asking, why do the good suffer and the bad prosper? In essence, it’s the same question Asaph of Israel asked in Psalm 74 and a perennial question that is asked by many people each day as they witness suffering and injustice in the world. Yet, it is Boethius’ answer that should surprise us. As a Christian, he does not write an exposition of Philippians 4:11, “I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances.” Nor does he write a martyrology that will allow him to see how much others have suffered for the name of Christ, giving him perspective that he really doesn’t have it all that bad. Instead, Boethius writes a theodicean dialogue where he finds consolation from Lady Philosophy. That’s right, Boethius turns to Philosophy, not Theology to find his great comfort, though what he learns is certainly overtly theological.

To see how masterfully he does this requires a slow and attentive reading of the text itself. My thoughts concern the applicability of Boethius’ method. Could it be that when counseling pastorally that I too could (or should) bring Lady Philosophy into the session? Have my past efforts at pastoral counseling been too simplistic? Did I really bring long-term consolation to those whom I counseled? It is tempting to sit with grieving Christian parents who may have miscarried early in a pregnancy assuring them that “God has a plan for all events in our lives, including the tragedies.” The statement is theologically correct, but pastorally insensitive. Though the couple may be saying, “why did God do this to us?,” they are likely asking a deeper question, “why do my friends who aren’t serving God having healthy children while I am unable to bring a child to birth?” A robust theological discussion of God’s agency in all of life’s events would be the last thing that this couple probably wants to hear. Rather, like Boethius they may find consolation in hearing that true living comes from participation in God. Though the impious may seem happy, true happiness is only found in God. These are the truths that Lady Philosophy was able to help Boethius see and understand, thus changing his perspective on why he was imprisoned and why he would ultimately be martyred. It brought him much-needed consolation. For me, Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy is a reminder that only Truth brings lasting consolation. Anything else will only be a Band-Aid on a gushing wound. My desire as a pastoral counselor must be to bring true consolation. Thus, my role is akin to that of Lady Philosophy — I have the words of wisdom, I must impart them in such a way as to bring deep and abiding consolation.