Martyrdom

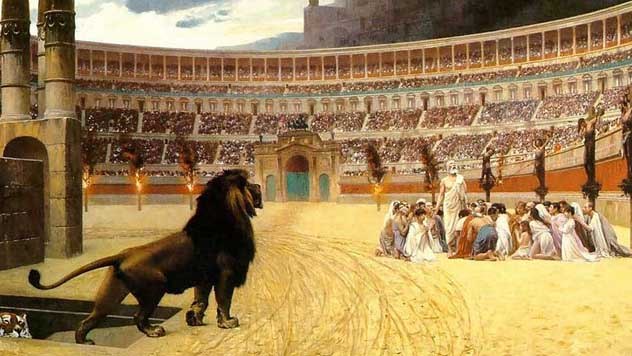

Martyrdom is a matter of finding oneself caught between an absolute and unyielding monotheism on the one hand (15, 39, 100), and an absolute and demonic claim to the contrary on the other. It is where we find ourselves forced to confess God at pain of death, or reject God to embrace a life without him. While few people that we know bear such scars in the American church, there have been periods and regions in the history of the church where such scars were abundant and even common place. Eusebius, writing at the end of such a period, offers us a beautiful and compelling account of martyrdom, rooted in numerous stories of these Christian victors.

While martyrdom isn’t so good that its end is bad (1; book X), it is nonetheless a great good, a matter of winning a crown; of suffering the same fate as Christ, at the hands of the same murderers (35, 268). But in sharing the same fate, we share the same blessing, the same calling to a crown, a trophy of the resurrection (85), a divine gift and honor unparalleled in the life of the church (12). For to suffer martyrdom is to be purified (99), to win a prize of an end like that suffered by the Lord (95), to “to attain to Jesus Christ” (98).

To avoid confession and escape martyrdom is to know you are unworthy and incapable of it (126), thus throwing away your salvation (118). To stand firm is to be sealed in your salvation (148), a great and blessed fulfillment (117).

But a gruesome death is a beautiful fulfillment only because of the context in which it occurs – a war against Satan (149). Apart from this cosmic battle, martyrdom makes little or no sense. For martyrdom, after all, is the tool of Satan (108) by which he attempts to crush the Church. But as we well know, Satan has no proper tools of his own: what seems to be a horrible mace wielded by his strong arm proves instead to be the legitimate weapon of Christ the King. It is one of the great tools by which he defeats Satan (142-3), making his sentence against the Serpent irrevocable (145). This is partly a matter of judging and proving Satan impotent. But it is also a matter of the powerful witness and example of the martyrs leading Satan “into vomiting up those he thought he had swallowed,” changing the minds of the weak and wayward as they watch the faithful triumphing over fear, death and the devil (149).

But is there more to it than this? For this much is unlikely to be new or surprising to those who have heard stories of the great martyrs. I believe there is, and it lies in the connection between the martyrs and the Lord: Jesus Christ, the Great Martyr.

Jesus Christ, The Great Martyr

Eusebius tells us of certain Christians:

So eager were they to imitate Christ, who though He was in the form of God did not count it a prize to be on an equality with God, that though they had won such glory and had borne a martyr’s witness not once or twice, but again and again, and had been brought back from the wild beasts and were covered with burns, bruises, and wounds, they neither proclaimed themselves martyrs nor allowed us to address them by this name: if any one of us by letter or word ever addressed them as martyrs he was sternly rebuked. For they gladly conceded the title of martyr to Christ, the faithful and true Martyr-witness and Firstborn of the dead and Prince of the life of God, and they reminded us of the martyrs already departed. (148)

Jesus is the martyr. He is “the faithful and true Martyr-witness and Firstborn of the dead and Prince of the life of God.” When caught between the one God, maker of heaven and earth, and the opposition and temptation of Satan, Jesus stood forth as witness. He is also the Firstborn of the dead and the Prince of Life because his faithful choice as martyr-witness. Much could be done here to unpack the meaning of Christ as martyr, but Eusebius himself takes us in fascinating direction.

In the concluding book of his History of the Church, Eusebius tells of the work of Christ, and how he “alone… took hold of our most painful perishing nature; alone endured our sorrows; alone He took upon Him the retribution for our sins” (308). But the surprising thing is that “now, as a result of this wonderful grace and bounty, the envy that hates the good, the demon that loves evil, bursting with rage, lined up all his lethal forces against us” (309). In other words, the great work of Christ set in motion an escalating process of retaliation on the part of Satan, in which he “vomited forth his own deadly venom, and by his noxious, soul-destroying poisons he paralyzed the souls enslaved to him, almost annihilating them by his death-bringing sacrifices to dead idols, and letting loose against us every beast in human shape and every kind of savagery” (309). The atonement, while it is the defeat of Satan, is simultaneously that which goads Satan into heightened opposition to Christ and the church – an escalation in the conflict.

This is where martyrdom comes in, for the martyrs are suffering the brunt of this escalation. What are we to make of this? Why does God choose to defeat Satan that way? Why through martyrs, when Satan’s defeat happened through Christ the Martyr once and for all?

Union with The Martyr

The answer lies partly in the fact that we, as the image of God, image forth the death and resurrection of Jesus. We, as those who are made in the image of God, image him forth as the one he is, and therefore as the crucified and risen one. Eusebius tells us that the martyrs present to the outward eyes of others “the One who was crucified for them, that He might convince those who believe in Him that any man who has suffered for the glory of Christ has fellowship for ever with the living God” (145), and that “the ever-present power” of “our Saviour Jesus Christ Himself” is “visibly manifesting itself to the martyrs,” and they in turn to those watching (263).

Ephesians seems to be of great benefit here. Collating several verses to sum up the flow of the letter, we see the gist of Paul’s argument:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places in Christ (1:3), in order that the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known through the church to the ruler and the authorities in the heavenly places (3:10). [Therefore] put on the full armor of God, that you may be able to stand firm against the schemes of the devil. For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the powers, against the spiritual forces of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places (Eph. 6:11-12).

Viewed in this light, the work of Christ is not a final and complete work in which we have nothing to do; rather, it is a final and complete work in the sense that it equips us for the work to which we were called, a work of opposing the schemes of the devil, one of which happens to be the devils attempt to crush the faith through martyrdom.

It is almost as though it is the place of the church to reveal Christ, by taking up his cross and triumphing over the powers of darkness in martyrdom. Why doesn’t the church just point back to Christ? Why embody him, repeating the cross? Or is Christ in that event, suffering and dying?

Eusebius tells us of a martyr whose body “was all one wound and bruise, bent up and robbed of outward human shape, but, suffering in that body, Christ accomplished most glorious things, utterly defeating the adversary and proving as an example to the rest that where the Father’s love is, nothing can frighten us, where Christ’s glory is nothing can hurt us” (142). In this story, the sufferings of the martyr and Christ’s sufferings become indistinguishable, and it is in and through the sufferings of the martyr that The Martyr accomplishes his work of defeating the adversary. In his grace, God gives us the opportunity to witness and testify to the work of Christ not from a distance, but from within, as we are united to him. It is in our work that Christ completes his work, of triumphing over Satan.

Colossians 1:24 reads: “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I do my share on behalf of His body (which is the church) in filling up that which is lacking in Christ’s afflictions.” Of course this must be unpacked carefully, but Eusebius gives us an interesting implicit account of how this “lack” might be construed: our God and Father calls the church to participate in Christ, in The Martyr, that in him, as martyrs in him, Christ might complete the ministry of reconciliation, spreading the good news of the Gospel, spreading the triumph over Satan—a work which is not alongside, after, or for the work of Christ, but which is the work of Christ, as we are in him and he in us, a participatory account of martyrdom.

The key is the extent to which God wants to bring us into his divine life. God wants us to be one with Christ, sharing in the work of Christ, through the power of the Spirit, to the glory of the Father. If we are to be united with God, then ours is the work of God. God does not will to work alone. And because in his wisdom he brings about his work through The Martyr-witness, Jesus Christ, ours also is a work of martyrdom, for ours is not an alien work, but a work that happens in, through, by and for him.