Dr. Rodrick Durst (Gateway Seminary of the West) recently published Reordering the Trinity: Six Movements of God in the New Testament (Kregel: 2015).

Dr. Rodrick Durst (Gateway Seminary of the West) recently published Reordering the Trinity: Six Movements of God in the New Testament (Kregel: 2015).

I’ve never seen anything quite like this book. The title Reordering the Trinity sounds edgy, like Durst is going to claim something wildly novel; maybe claim that the Father proceeds from the Spirit or something joltingly unorthodox like that. Instead, Durst does something so basic and obvious that anybody with an English Bible could have done it at any time, but nobody did. He just goes through the New Testament and catalogs all the Trinitarian passages to see what sequence the three persons are named in. That catalog (captured in a series of lists, charts, and graphs) is the foundation of the book.

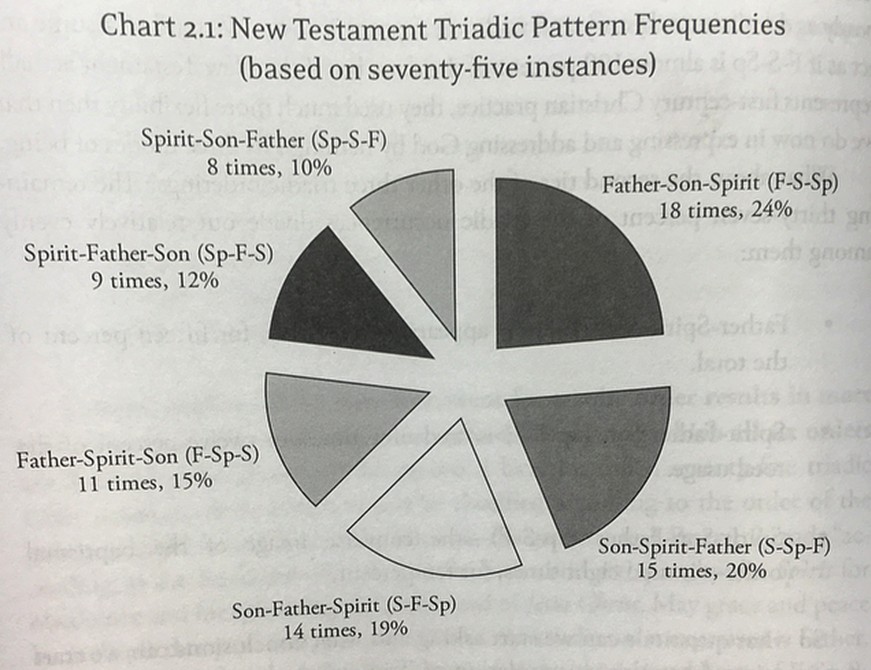

It’s simple math that any three terms can be arranged six ways, and sure enough, in the New Testament Durst finds all six of the possible configurations. Here’s a pie graph:

The Father-Son-Spirit sequence graphs at eighteen occurrences; while Spirit-Son-Father only has eight. I won’t identify all the elements in this data that surprise me; the graph really speaks for itself and invites exploration. What a fruitful, quirky, fascinating graph!

Durst’s next move, to which the bulk of the book is devoted, is to consider each of these triadic patterns in each of their contexts, to see what might be revealed about the Triune God’s interactions through each pattern. What he discerns is six meaningful triads, and he develops a little Biblical theology around each of them:

The Sending Triad / Missional Order

The Saving Triad/Regenerative Order

The Indwelling Triad/Christological Witness Order

The Standing Triad/Sanctifying Order

The Shaping Triad/Spiritual Formation Order

The Uniting Triad/Ecclesial Order

That’s the short description of his approach, which I think is glaringly obvious and somehow counter-intuitive at the same time.

Durst’s innovative approach deserves wider discussion than I’ve seen it getting so far. I know Rick from some work I’ve done with doctoral students at Gateway Seminary (waaay back last year when it was Golden Gate Seminary), so I sent him a few of the questions that came to mind as I studied Reordering the Trinity. Here are his answers.

FS: Rick, congratulations on this new book with its unique approach to biblical Trinitarianism.

FS: Rick, congratulations on this new book with its unique approach to biblical Trinitarianism.

I want to start with a number: 75. You count 75 instances of triadic configurations in the New Testament. I’ve mentioned that to a few colleagues and students over the last several months, and they’re surprised how high the number is. I think they were expecting a dozen, maybe two dozen. They experience an almost evidential force just in the quantity. How’d you come up with 75? Did you have to, shall we say, cheat at all, to get such a high number?

RD: Fred, I never intended to find a big number of triadic references in the New Testament, but I was determined to find them all. I was cautious, because in the office next door to me was a well-published NT scholar who I respected, and knew would be checking my work!

When I presented my findings at one of our graduate studies gatherings, David Howard of Bethel Seminary was present, and suggested that if I could come up with some kind of grading system, then I might really have something. So for a triadic reference to get an “A” grade, that reference had to have all three names in close order and be rather intentionally trinitarian, like Paul’s triadic benediction in 2 Cor. 13:14 or Peter’s trinitarian greeting in 1 Peter 1:2. Both have different triadic orders than the traditional expectation.

And maybe that’s the point: I wanted to stop reading the Bible like a tourist who only sees what he or she has been told to see, and to read it like G. K. Chesterton’s challenge to be a traveler who goes out to see what all is there.

FS: Well said!

FS: Well said!

I have a question about how you made your decisions. You identified Romans 5:1-5 (we have peace with God through Christ, and the Spirit pours out God’s love in our hearts) as an instance of Father-Son-Spirit, the missional triad. But if we were to start, instead, with verse 5’s assertion that the love of God (the Father) is poured out through the Spirit, and that Christ died for the ungodly (verse 6), then we’d have Father-Spirit-Son, the the Spiritual Formation order. Why did you opt for the first rather than the second? And why not use both?

RD: Fred, you have put your finger on some of the difficulty and arbitrariness of my assignment. I realized that there is some room for rethinking some specific passages. I settled on a grade of “B” for this instance, for the ambiguity of the order. If I applied my notation scheme, Romans 5:1-5 comes out Father-Son- (v.1)-Father (v.2)-Father-Spirit (v.5). This passage might even be a prooftext in the hands of the Orthodox objections to filioque.

In Romans, Paul creates a trinitarian symphony in which he choreographs the interplay of the Three almost inadvertently, but obviously showing the inner differentiation without division in the Godhead.

FS: I suppose there must be an objection to your method that runs something like this: To treat the sequence of these occurrences as deeply meaningful is to over-invest in word order, and confuse syntax with semantics. How would you respond?

FS: I suppose there must be an objection to your method that runs something like this: To treat the sequence of these occurrences as deeply meaningful is to over-invest in word order, and confuse syntax with semantics. How would you respond?

RD: I may be guilty, but you would have to prove it using the preponderance of the NT evidence. The reason I drilled down into the texts exegetically was to make sure I was not operating in a semantical dreamland.

If the texts keep putting the named Three up on the board, who I am not to try and make sense of it? As I indicated in the book, I am not the first by any means to start collections of these sometimes inadvertent references to the Trinity. I just wanted to find all the pieces to the puzzle and then assemble it.

Even if 30% of the instances identified are thrown out of the court of consideration, fifty instances still remain to affirm that, the binitarianism of the Father/Son not excluded, Trinity-think was a part of the default consciousness of the NT writers discipled by Jesus.

FS: Sometimes the word order of the original Greek sentences has to be modified to make for readable English. Did you notice any places where that affected your decisions?

FS: Sometimes the word order of the original Greek sentences has to be modified to make for readable English. Did you notice any places where that affected your decisions?

RD: Knowing the scrutiny that I hoped would come because of the book, and that many would like to see some, if not many, of the cited instances thrown out, I always deferred to the order in the Greek.

Which raises another fun issue about translation of the OT. The English translations never follow accurately the grammatical oscillations of the Hebrew texts in which the Godhead is self-revealing; otherwise the English would read awkwardly (as does the Hebrew) “the Gods is crazy!”

As a theologian of classcial Trinitarianism, I’m bound to play favorites with the Father-Son-Spirit order, which is a kind of bedrock for some very good reasons.

But I also really appreciated the fruitfulness of your method when it came to Ephesians 2:18, where Jews and Gentiles both come through Christ, by the Spirit, to the Father. The sentence sequence itself does tell a little story, and it’s the story of salvation.

After examining all of them, do you have a favorite sequence or triad?

RD: I do like your preference for the Father-Son-Spirit order. I believe the NT uses that order as a sort of first test of orthodoxy.

That being said, my point in the book is that the NT pointedly calls us to praise, pray and preach in all six of the orders. Maybe we have little preaching on the Trinity because most of the NT trinitarian texts are not in the expected order.

Now that being said, at the moment I am reflecting most often on the Spirit-Father-Son order, because in my present ministry of leading the startup of a new seminary campus in Fremont, many missional risks are involved and many decisions required with Christian integrity. When I call upon God the Spirit to fill me who a vision of the Father’s glory and sovereignty, that vision is accompanied with an experience of the Son standing up for me and beckoning me to stand in the new day for Him.

FS: Your final chapter offers guidelines for “becoming a functional Trinitarian.” Just how dysfunctional do you think evangelical Trinitarians are right now, and how would you like to see the ideas in your book change that?

FS: Your final chapter offers guidelines for “becoming a functional Trinitarian.” Just how dysfunctional do you think evangelical Trinitarians are right now, and how would you like to see the ideas in your book change that?

RD: As an Evangelical church insider, I think we are more functionally Trinitarian than we believe. God is too, well, God not to be present to be worshipped as He is and reveals.

RD: As an Evangelical church insider, I think we are more functionally Trinitarian than we believe. God is too, well, God not to be present to be worshipped as He is and reveals.

I do think naming the Trinitarian “elephant in the room” is adult, helpful and attendant to the sola scriptura value we embrace. In view of the difficulty of faithfully holding fast to the mystery of God’s triune way of being, it is a wonder that in 2000 years of Church History the church has stubbornly refused not to be Trinitarian.

I believe some of the reason for that obstinate Trinitarianism is that every time we turn a page in the NT, the triune Godhead “pops up” in unexpected ways and orders. That textual pressure compels us to be Trinitarian. I also contend that the deep source of rigid, letter-of-the-law legalism and/or spiritual behaviorism is the operational modalism where the Anglicans have the Father, the Baptists have the Son and the Pentecostals have the Spirit. On the other side of the creedal highway, I also contend that the deep source of racism and genderism is a crafty subordinationism that insists that the Father alone is the high God, and then invents high-sounding but nevertheless deity-demeaning titles for the Son and the Spirit. Here I would come back to what you have been saying in your books, Fred: right understanding and life in the Trinity changes everything.