(This is the opening section from a sermon I preached on Sept. 10, 2013 in Talbot chapel. Full video here.)

(This is the opening section from a sermon I preached on Sept. 10, 2013 in Talbot chapel. Full video here.)

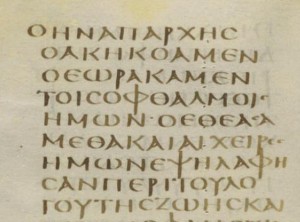

In the first five verses of his first epistle, John seeks to sum up everything he ever heard, everything he ever saw, everything he came into contact with, about the person he wrote a whole gospel about: Jesus Christ. It’s a remarkable feat, because that gospel of John, that twenty-one chapter gospel, ended with a confession that there’s too much content in the reality of Jesus to ever capture in print: “Now there are many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.” (John 21:25) Think about that: there’s way too much to say, but here it is in 21 chapters.

And now it’s as if somebody has pressed him and said, thanks for boiling that all down to 21 chapters, John, much more portable than a world full of books; but it’s still a pretty long book. Could we get an executive summary of that? Could you say it even more concisely? Could you leave out the fluff and just state the big, main point? Could you maybe get that down to about, I don’t know, three words?

John would be perfectly justified in responding to this (imaginary) request with a NO. After all, some things just can’t be stated briefly. Some subjects require you to go along for the journey, to start at point A and walk patiently through a series of stations (B,C,D,E…) until arriving at the destination. To summarize it would be to leave out the whole purpose of it. Imagine asking a language tutor to tell you how to speak Spanish, but to leave out the details. “How do I speak Spanish?” “Well, it’s a skill and a process. You’ll need a lot of vocabulary, and some usage and grammar and habits of thought…” “Yeah yeah yeah, but I’m in a hurry, leave out the details and just tell me the basic idea of how to speak Spanish.” That doesn’t even make sense. “You know not what you ask.” No entiende… however that goes.

Some things, some of the most important things, resist being condensed and summarized. I think of the old one-liner from Woody Allen, who said “I took a speed reading course and read ‘War and Peace’ in twenty minutes. It involves Russia.” At that rate, Woody Allen could complete the reading list for the Torrey Honors Institute not in four years but in a few days, with similar results for all the classics of western literature:

The Iliad: Big big fight.

The Odyssey: Dude goes home.

Moby-Dick: Crazy captain chases white whale; hilarity ensues.

Paradise Lost: OOOPS.

And so on.

So, John: could you capture the most important things we learned about God from Jesus? “Well, in 21 chapters I can get the most important bits.” Okay, great, now three words. Why didn’t John refuse? What he has to say is too rich, too full, too exquisitely good to summarize, isn’t it?

Just look at the first four verses here: “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, etc.” You could summarize that if you wanted. Here’s my summary: “We proclaim to you something we encountered, so you can share in it.” That’s a pretty good summary and simplification, I think. I worked pretty hard at it, and I think I nailed it: I even wrangled the subject-verb-object relationship into a clearer order than in the original. “We proclaim to you something we encountered, so you can share in it.”

I admit I had to leave out some details like the noble progression and intensification of intimacy from hearing to seeing to really looking at intently to touching. That’s a loss. And I skipped the “word of life” bit altogether, which maybe was a mistake. And by cleaning up the word order I obliterated the sense of expectation and suspense that the author was going for. I failed to mention that it was in the beginning with the Father, which is probably really important if I ever want to get to the doctrine of the Trinity. In fact, the more I look at my summary, the less proud I am of it, and the more I think the cost of simplification was too high. “Ooops.”

Since we’ve already referred to several of the great classics of literary history, perhaps it’s safe to refer to one more classic: the episode of the Simpsons where Homer has heart surgery. It’s from season four, that makes it classic. Homer suffers a heart attack, and his doctor, Dr. Hibbert, says:

“Homer, I’m afraid you’ll have to undergo a coronary bypass operation.”

Homer replies: “Say it in English, Doc!”

Dr. Hibbert: “You’re going to need open-heart surgery.”

Homer “Spare me your medical mumbo jumbo!”

Dr. Hibbert: “We’re going to cut you open and tinker with your ticker.”

Homer: Could you dumb it down a shade?

No, sorry, Homer, that’s as dumb as it gets. If we leave out anything else, we’ve left out the heart of it, so to speak.

So my summary: “we proclaim to you something we encountered, so you can share in it” runs the risk of tinkering with the ticker of the letter of First John. But maybe it was clarifying for you to hear the super-short version. Sometimes a blunt, summary simplification is a good tool, if and only if (that’s for you philosophers) –if and only if the summary sends you back to the original to re-gather and re-experience all the richness of the real thing. Holding the little thumbnail sketch, “we proclaim something we experienced,” in mind can help you keep your bearings through all the delayed gratification of “that which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and have touched with our hands…” It reminds you that the verb is coming, just be patient. Sometimes if you’re getting lost in the details, you do need someone to remind you, “It involves Russia.” Then you can go back and work through all those long names of people and places, all the characters and battles and events.

“Map is not territory,” they say. But while I was never tempted to move into a map and live there, there have been times when I was awfully glad to have the map. The joy is still in the journey, the delight is all in the details, but sometimes the simple summary sets you free to immerse yourself in the richness of the unedited reality of the thing itself.