People claim to believe all kinds of things, but if you want to find out what they really believe, see what they can sing about. As I’ve tried to identify what the great evangelical tradition has believed about Scripture, I have found plenty of arguments, manifestos, controversies, and declarations. But I also found a hymnal which was specially designed to emphasize the Bible and our approach to it. It’s a hymnal that features fifty hymns about Scripture itself! I’ve learned more from this rich vein of evangelical hymnody than I have from a whole stack of books, and one of the things I’ve learned is that when evangelicals sing about Scripture, they sing about the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Their approach to Scripture is trinitarian.

People claim to believe all kinds of things, but if you want to find out what they really believe, see what they can sing about. As I’ve tried to identify what the great evangelical tradition has believed about Scripture, I have found plenty of arguments, manifestos, controversies, and declarations. But I also found a hymnal which was specially designed to emphasize the Bible and our approach to it. It’s a hymnal that features fifty hymns about Scripture itself! I’ve learned more from this rich vein of evangelical hymnody than I have from a whole stack of books, and one of the things I’ve learned is that when evangelicals sing about Scripture, they sing about the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Their approach to Scripture is trinitarian.

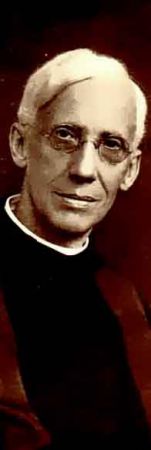

The man responsible for gathering these hymns is George Campbell Morgan (1863-1945). Morgan used to be more famous than he is now. Best known as the pastor of Westminster Chapel in London, he also worked in the United States with Dwight L. Moody’s many projects, and taught widely in Bible Institutes. One contemporary called him “the hardest working preacher in Christendom.”

Morgan could make himself at home in many denominational settings: his father was a Baptist pastor, while Morgan sought (but was refused) ordination from the Methodists, and eventually was ordained as a Congregationalist, though he later pastored in a Presbyterian church. He was famous and influential in his time, and anything he said would count as important information. But I am invoking G. Campbell Morgan not so much as an author as for his editorial judgment. In 1911 he edited a hymnal, The Song Companion to the Scriptures (London: Morgan and Scott, 1911), which he described this way in the preface:

This Hymn-book has been prepared to meet the demand created by the growth of the Bible-school movement. While many excellent Hymnals are extant, suitable for the regular services of the Church, for special Conventions and Meetings for the deepening of the spiritual life, and for Evangelistic Services, no book has been provided specially suited to the needs of assemblies gathered specifically for the study of the Divine Library.

The plan, as indicated by the Contents Pages, is purely Biblical. A very special feature is that of the large number of hymns on the Word of God, which have been gathered with extreme care.

Morgan scoured all available sources and managed to come up with a “large number of hymns on the Word of God.” He finds, in fact, fifty hymns on the Word of God. Fifty love songs to the Bible! Evangelicals are often accused of bibliolatry, book-worship, because of the high place they give to Scripture. If singing fifty love songs to the Bible is not bibliolatry, what is? If this is not replacing the living God with a stable text, what would be? Let me alarm you about how much these songs exalt the book, before I soothe you by showing you that bibliolatry is not an option for the evangelical trinitarian approach to Scripture.

Hymn #100 is John Newton’s “Precious Bible,” while in Hymn # 114, John Fawcett sings

How precious is the Book Divine,

By inspiration given!

Bright as a lamp its doctrines shine

To guide our souls to heaven.

Fawcett goes on to attribute all sorts of saving actions directly to the book:

Its light, descending from above,

Our gloomy world to cheer,

Displays a Saviour’s boundless love

And brings His glories near.

“It shows to man his wandering ways,” he says, and “When once it penetrates the mind/ It conquers every sin.” What else does it do? “Life, light and joy it still imparts.”

Hymn #106, by Thomas Kelly (1769-1855), sings directly to the personified book:

Precious volume! What thou doest

other books attempt in vain:

Plainest, fullest, sweetest, truest,

All our good from thee we gain.

And

Precious volume! All revealing,

All that we have need to know.

Kelly is also the author of Hymn # 134, which begins by testifying

I love the sacred Book of God,

No other can its place supply—

It points me to the saints’ abode;

It gives me wings, and bids me fly.

but by the second stanza is again speaking to the personification of the book itself:

Blest Book, in thee my eyes discern

The image of my absent Lord:

From thine instructive page I learn

The joys His presence will afford.

A critic who approaches the evangelical tradition with suspicion could surely find in these lines all the evidence necessary to declare that this hymnal is primary evidence of the evangelical displacement of the living God by a book: The “Blest Book” shows the believer “the image of my absent Lord.” What can this mean but that Jesus is gone and he left behind a document? However, Kelly’s hymn goes on to reflect on what will happen when “my absent Lord” returns with “the joys” of “His presence:”

Then shall I need thy light no more,

For nothing then shall be concealed;

When I have reached the heavenly shore

The Lord Himself will stand revealed.

When ‘midst the throng celestial placed

The bright original I see,

From which thy sacred page was traced,

Blest Book! I’ve no more need of thee.

The whole hymn is an exploration of the relationship between the book and the Lord. Kelly speaks to the personified “Blest Book” only about how it brings Christ before his attention, and after saying that there will come a day when he’ll have no more need of the Bible because Christ will be directly present, Kelly concludes,

But while I’m here thou shalt supply

His place, and tell me of His love;

I’ll read with faith’s deserving eye,

And thus partake of joys above.

The fact is that far from bibliolatry, when we catch evangelicals in the act of singing about their Bible, we catch them singing to and about God, and increasingly about the Son and the Spirit. In Hymn #125, Horatius Bonar sings

Thy thoughts are here, O God,

Expressed in words Divine,

The utterance of heavenly lips

In every sacred line.

And

Each word of Thine a gem

From the celestial mines;

A sunbeam from that holy heaven

Where holy sunlight shines.Thine, Thine this Book, though given

In man’s poor human speech,

Telling of things unseen, unheard,

Beyond all human reach.

Bonar knows that you need not make an idol of the Bible to be able to say that “What Scripture says, God says.”

Morgan includes Mary A. Lathbury’s “Break Thou the Bread of Life,” which has the lines:

Break Thou the Bread of life,

Dear Lord, to me,

As thou didst break the loaves

Beside the Sea.Beyond the sacred page

I seek Thee, Lord:

My spirit pants for Thee,

O living Word.

The personalism of Lathbury’s “beyond the sacred page” echoes the eschatological tones of Kelly’s “Blest book, I’ve no more need of thee.” And in hymn #103, T. T. Lynch sounds like Adolph Saphir when he writes, ‘Christ in his Word draws near; hush, moaning voice of fear, he bids thee cease.”

Many of these hymn writers are willing to play on the similarity between the incarnate Word and the written word, which raises the question of whether they are aware of what they are doing when they make this move. It seems increasingly likely that they are doing this in full cognizance of the difference when we note the way other authors in the collection handle the difference between Word and word. Listen to the way W. W. How (hymn #105) traces the connection between the incarnate Word and the written word:

O Word of God incarnate,

O wisdom from on high,

O truth unchanged, unchanging,

O light of our dark sky;We praise Thee for the radiance

That from the hallowed page

A lantern to our footsteps,

Shines on from age to age.

Mr. How praises Jesus for providing the guidance of the Scriptures for his people:

The church from thee, her master,

Received the gift divine,

And still that light she lifteth,

O’er all the earth to shine.It is the golden casket

Where gems of truth are stored;

It is the heaven-drawn picture

Of Thee, the living Word.

He pictures Scripture as the “golden casket” in which are stored gems of truth, given radiantly by the Word incarnate.

The believer’s dependence on God’s trinitarian action to make himself directly known in Scripture is a recurring theme in several hymns, including the anonymous hymn #112:

A glory in the Word we find,

When grace restores our sight;

But sin has darkened all the mind,

And veiled the heavenly light.When God’s own Spirit clears our view,

How bright the doctrines shine!

Their holy fruits and sweetness show

The author is divine.How blest are we, with open face,

To view thy glory, Lord,

And all thy image here to trace,

Reflected in thy word.

With increasingly explicit trinitarianism, William Cowper’s hymn “The Spirit and the Word” (#113) says,

The Spirit breathes upon the Word,

And brings the truth to sight,

Precepts and promises afford

A sanctifying light.A glory gilds the sacred page,

Majestic, like the sun,

It gives a light to every age,

It gives, but borrows none.The hand that gave it still supplies

The gracious light and heat,

Its truths upon the nations rise

—they rise, but never set.

Charles Wesley’s presence is strong in this miniature hymnal-within-a-hymnal about the Bible, and his hymns are, as always, marked by pronounced theological literacy. In hymn 101 he sings to the Holy Spirit,

Come, Divine Interpreter,

Bring us eyes Thy Book to read,

Ears the mystic words to hear,

Words which did from thee proceed.

He cannot decide whether the decisive action of revelation is properly Christological or pneumatological, so he writes entire hymns alternately to Christ the Prophet, and the Holy Spirit of truth. Hymn #123 runs:

Come, o thou prophet of the Lord,

Thou great interpreter divine

Explain thine own transmitted word,

To teach and to inspire is thine,

Thou only canst thyself reveal—

Open the book and loose the seal.Whate’er the ancient prophets spoke

Concerning thee, O Christ, make known,

Chief subject of the sacred book,

Thou fillest all, and thou alone

Yet there our Lord we cannot see

Unless thy spirit lend the key.Now, Jesus, now the veil remove

The folly of our darkened heart,

Unfold the wonders of thy love,

The knowledge of thyself impart

Our ear, our inmost soul we bow,

Speak lord. Thy servants hearken now.

Wesley’s hymn #127:

Spirit of truth, essential God,

Who didst thy ancient saints inspire,

Shed in their hearts thy love abroad,

And touch their hallowed lips with fire;

Our God from all eternity,

World without end, we worship thee.Still we believe, almighty Lord,

Whose presence fills both earth and heaven,

The meaning of the written word

Is by thy inspiration given.

Thou only dost thyself explain

The secret mind of God to man.Come then, divine interpreter,

The scriptures to our hearts apply,

And taught by thee, we God revere,

Him in three persons magnify;

In each the Triune God adore,

Who was and is forevermore.

And his #121:

Inspirer of the ancient seers,

Who wrote from thee the sacred page,

The same through all succeeding years,

To us, in our degenerate age,

The Spirit of thy word impart,

And breathe the life into our heart.While now Thine oracles we read

With earnest prayer and strong desire,

Oh let thy spirit from thee proceed

Our souls to awaken and inspire.

Our weakness help, our darkness chase,

And guide us by the light of grace.

Morgan places these Christ and Spirit hymns side by side, because it is just good tacit trinitarian theology to recognize that the Spirit makes Jesus Christ present to us as the Word of the Father, and that hearing the voice of God in Scripture is a single, concerted, trinitarian event. Morgan’s editorial hand also shows up in the architecture of the hymnal. Having found these fifty hymns on the word of God, he arranges them very thoughtfully within an overall trinitarian structure. First, he signals his intention by opening the hymnal with Section One: The Holy Trinity, a section which contains five songs on the Trinity. The next three sections are:

II. The Revelation: The Father (12 hymns)

III. The Revealer: The Son (70 hymns from advent to second advent)

IV. The Interpreter: The Holy Spirit.

This long section of hymns on The Holy Spirit, the Interpreter, is divided into two sections: Fifty on the Interpreter “In the Scriptures,” followed by twenty-one on the Interpreter “In the Heart.”

G. Campbell Morgan not only had a keen editorial eye for the trinitarianism implicit in evangelical Bible reading, but also understood how it fit into the overall pattern of Christian truth. When he put the fifty hymns on Scripture into a trinitarian outline, he wasn’t forcing them anywhere they didn’t belong. As an evangelical who knew what he was about, he was merely making explicit the deep trinitarianism implicit in the characteristic evangelical approach to Scripture.