Genevieve Foster is the author of a number of histories for young readers, published in the forties and fifties. Foster is a great story-teller who knows how to include all the information you’d expect in a kids’ history, but who also reads widely enough to gather up some surprises from primary text and older histories.

Genevieve Foster is the author of a number of histories for young readers, published in the forties and fifties. Foster is a great story-teller who knows how to include all the information you’d expect in a kids’ history, but who also reads widely enough to gather up some surprises from primary text and older histories.

But one thing (not the main thing –see below for that) that sets Foster’s work apart from any other mid-century kids books in the “Western Civ and Why It’s Great In The Fifties In America” genre is her decision to explore more broadly than mere biography. She hangs each volume on a major figure, but instead of giving us, for example, Abraham Lincoln’s Life, she gives us Abraham Lincoln’s World –and that makes a big difference. Her Lincoln volume is certainly a serviceable biography of the sixteenth president, but Foster works out from there to as much world history as she can cram in: European history is well covered, but there is also reporting on Japan and Africa.

In the case of Christopher Columbus, Foster’s The World of Columbus and His Sons looks all over the world of the late fifteenth century to see what was going on. You may just pick up the book for the explorer whose name means “Christ-Carrying Dove,” but you’ll get a lot of Gutenberg, Leonardo, the Wars of the Roses, Machiavelli, Ivan III, Savanarola, Michelangelo, Erasmus, and so on. There’s a bit of history from outside the European context as well. Not a lot, admittedly, because Foster’s works tend to be in the “West plus the Rest” genre, but you’ll meet Budomel, Batti Mansa, and other figures who weren’t showing up in most mid-century elementary curricula. I’m not saying Foster passes early twenty-first century standards for inter-cultural sensitivity, but she’s still eminently readable and instructive after a very eventful half-century with its revolution in historical sensibilities. Foster had a sense of parallel developments and global interrelatedness that runs right up to the brink of synchronicity, but if she has a grand unified theory in mind, she avoids making it explicit. She seems to consider her work done when she has laid out the world cultures side by side.

Genevieve Foster majors in interconnections, and her focus on the West lets her keep the connections rich. She expertly trails out little bits of information from the very first page, so that by the time she concludes her story, the reader’s mind is well stocked with all the information needed to get the punch line. As Ferdinand Columbus goes through his library, he sets down a 1520 edition of the Antibarbari autographed by Erasmus, and picks up a book by the Cordova-born Roman philosopher Seneca: “An age will come after many years when the ocean will loose the chain of things, a huge land will lie revealed; Tiphys will disclose new worlds and Thule will no longer be ultimate…” Ferdinand writes in th e margin, “This prophecy was fulfilled by my father, the Admiral, in the year 1492.” KAPOW! If you’ve been paying attention to Foster’s story so far, you feel the significance of every bit of information there.

These books are too good to continue being the secret of homeschoolers. Everybody else should get in on the fun.

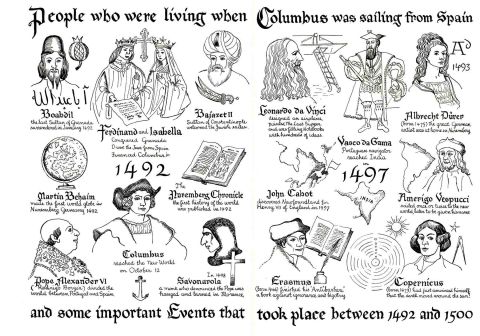

Because here’s the best thing in Genevieve Foster’s World Of histories: the illustrations. Before every major section, Foster gives a kind of “horizontal history” or cross-section of what’s happening in the world during that portion of the hero’s life. For example, here’s the two-page spread from the crucial 1492 section of the Columbus book:

So much education… flooding my mind… can’t keep reading! Most of her cartoons are based on paintings and carvings contemporary with the events, so these simple line drawings also provide a bit of visual literacy. I wish these had been on the shelves in my house when I was a kid.