When Paul wrote, in Romans 1:18, that people “suppress the truth in unrighteousness,” he described a remarkable, and remarkably universal, human habit.

Everybody suppresses the truth in unrighteousness, and almost nobody knows they’re doing it while they’re doing it. You can hardly catch yourself in the act of suppressing the truth. But here’s how you know it happens: After you stop, you can look back and see in retrospect that you were doing it.

We experience this particular kind of self-deception in daily life when we do things like tell ourselves we can absolutely make it through a yellow traffic light, and we keep on believing it until we see the light turn red above us, or even a few yards ahead of us. The moment when we were saying “I know I can make it” is when we were suppressing the truth. The moment when we see the light turn red while our car is still in the middle of the intersection is when we admit, “I knew I couldn’t make.” That’s when we know we were fooling ourselves.

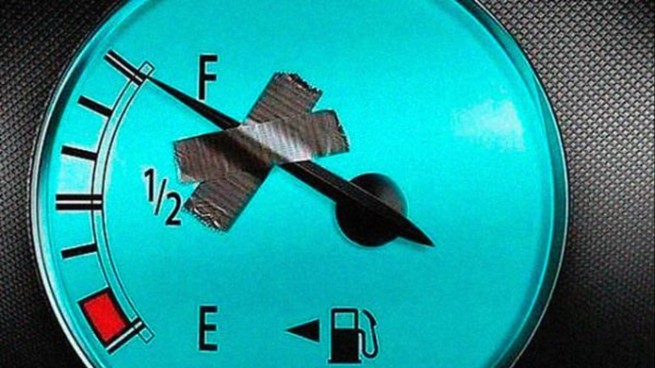

There are more dramatic situations to consider. To keep the illustration vehicular: we tell ourselves we’ve got plenty of gas, until we run out of gas and immediately say, “I knew I’d run out.”

Once you’ve caught yourself doing this a few times, if you’re a reasonable person you’ll consider adding a new item to the list of Things You Do: Apparently I suppress the truth in unrighteousness, but can’t tell I’m doing it until I stop. The implication seems to be that you’re likely to be doing it now; or at least that if you are doing it now you’re unlikely to be noticing it in real time.

Jane Austen is one of the great narrators of characters who suppress the truth. As C.S. Lewis pointed out in an essay about Austen, four out of six of her novels turn on a clueless character who finally gets undeceived, runs the mental tapes, and realizes that everything is the opposite of how it first appeared. Reading Austen is, among other things, exercise for the capacity to catch oneself self-fibbing. Good readers of Austen are not only amused by moral blindness in her characters, but are alert to the possibility of moral blindness in themselves.

A more urgent example from contemporary life is racial bias. Let’s say there’s racial bias at work in our culture, embedded in things like social structures, historical legacies, city plans, media stereotypes, and stock responses. Or let’s just say somebody claims there’s such a thing. Before dogmatically announcing that there can’t be any such thing because I can’t see any such thing, it’s worth asking: Do I have good reason to expect that I’m the kind of person who would see it if it were there? Am I at the correct angle to see such things? Do I have motivation to see them, if they’re there? Would I know I was suppressing this truth if I were in fact suppressing this truth?

The Bible knows all about this structure of self-deception and truth-suppression, and not just in Romans 1. In 2 Peter 3:5, the apostles tells us people who are “willingly ignorant” of a truth, and in Acts 7 a crowd who is tired of listening “cried out with a loud voice and stopped their ears.” We might describe it as what original sin looks like inside of your cognitive habits; the noetic effects of the fall of humanity; total depravity in epistemic form.

Some sins are probably the high-handed, eyes-wide-open, sinning-on-purpose kind of sins. But what a vast terrain of wrongdoing and wrongthinking must lie in this domain of the suppression of truth in unrighteousness. This is the insidious stuff, hard to repent of because hard to detect in the present tense. To confess sin is to agree with God about it, calling it the same thing he calls it. Confessing yesterday’s sin, as we are given light today to see it, is good progress toward tomorrow.