It’s not leftovers, it Scriptorium Classic! Reposted from Dec 25, 2007.

And I Joseph was walking, and was not walking; and I looked up into the sky, and saw the sky astonished; and I looked up to the pole of the heavens, and saw it standing, and the birds of the air keeping still. … And I saw the sheep walking, and the sheep stood still; and the shepherd raised his hand to strike them, and his hand remained up. And I looked upon the current of the river, and I saw the mouths of the kids resting on the water and not drinking…

The Bible doesn’t tell us everything we’d like to know. As it tells us the stories of God’s ways with the world, it leaves out things we would have included. That’s because God wrote the Bible with serious business in mind, not just the satisfying of our curiosity. In the Christmas story, for instance, it leaves out some details that we’d love to have, details that would be included in a normal biography: what kind of homes did Mary and Joseph grow up in, how did they meet, how did Mary’s pregnancy go, etc. And how about the early life of Jesus Christ: how did young Jesus learn the alphabet, what did he play with, and who were his friends? Sometimes we can’t stand not knowing, and we fill in the gaps with likely stories: Jesus must have been a carpenter apprenticed to Joseph, probably homeschooled, and so on.

Christians have been doing this kind of imaginative filling-in-the-gaps for a long time. In the first few centuries of the church, fake gospels started circulating, and became very popular. Some of them are from the third century and contain things that cannot be believed or taken seriously: boy Jesus bringing clay birds to life, or losing a race and making his opponents drop dead, or teaching his kindergarten teacher how to understand the mystical depths of the alphabet. Things like these amount to urban legends from the early church, though Time, Newsweek, and PBS will insist on bringing them up twice a year as if their existence proves that Christianity is hogwash and the canonical gospels are unreliable.

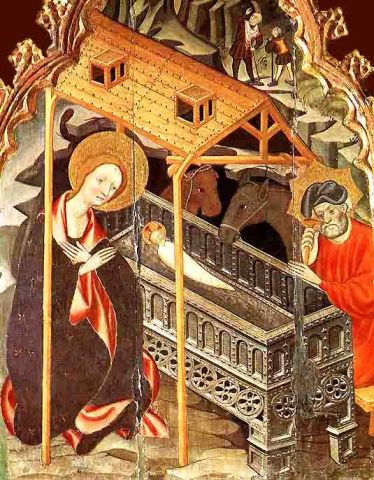

There is one infancy gospel, however, which stands out from the rest for several reasons. This writing, which is called either the infancy gospel of James or the Protevangelium of James, is older than most of its rivals. Nobody knows exactly when it was written, but Christian writers from the second century are already familiar with it: Justin Martyr (ca. 100-165) seems to know some of the traditions in it, and Origen (ca 185-254) quotes from it. The other element that makes this Protevangelium somewhat superior to the other works of its genre is its restraint: it doesn’t have a whole series of astonishing miracles that keep trying to impress the reader. There are a few miracles: a dove comes flying out of a stick and lands on Joseph’s head to let the priests know that he should be Mary’s guardian. But that’s mild stuff as these pseudo-gospels go, and the Protevangelium of James is mostly concerned with giving background information on Mary. This document is the source of the tradition that Mary’s parents were named Joachim and Anna, that Joseph was an elderly widower with adult sons from his first marriage, and so on. Information like this is very helpful if you want to interpret some of the details of Christian art from the catacombs to Giotto.

This is also the first place we hear the idea that the stable where Jesus was born was inside of a cave, and that brings us to the most fascinating passage in the Protevangelium. Here is an excerpt from chapter eighteen. Joseph has just put Mary into a cave and left her in the care of his two sons. He goes out into the night to find a midwife who can help with the delivery of the baby. Suddenly he speaks in the first person:

And I Joseph was walking, and was not walking; and I looked up into the sky, and saw the sky astonished; and I looked up to the pole of the heavens, and saw it standing, and the birds of the air keeping still. And I looked down upon the earth, and saw a trough lying, and work-people reclining: and their hands were in the trough. And those that were eating did not eat, and those that were rising did not carry it up, and those that were conveying anything to their mouths did not convey it; but the faces of all were looking upwards. And I saw the sheep walking, and the sheep stood still; and the shepherd raised his hand to strike them, and his hand remained up. And I looked upon the current of the river, and I saw the mouths of the kids resting on the water and not drinking, and all things in a moment were driven from their course.

Joseph of Bethlehem, a humble carpenter in a bad situation. He just stepped out of a cave into: the twilight zone.

The episode would be easy to dismiss: a ghost story in a fake gospel from a credulous age. But even if you don’t take it as historically true, there is something haunting about it. Joseph steps out of the small chamber where the miracle of the incarnation is taking place, and he doesn’t see everything going on as usual. He sees time stand still. The coming of Christ, we know, took place “in the fullness of time” (Galatians 4:4, Ephesians 1:10). Time itself was filled up, was ripe, had reached completeness. God had elected this moment as the center point of his redeeming and revealing activity.

If you could behold that moment of the fullness of time,and then turn your attention to the rest of time, how would everything else look? Common sense says that the single event in the stable would be just one moment in a larger flow of time. The rest of time would be the context that gave place and proportion to the time of the birth of Christ. Anybody with a stop watch could tell you that time may seem to stand still for the parents when the baby is born, but it’s just a trick of perspective and adrenaline.

And common sense presses a strong claim: No matter what was happening in the borrowed manger of Bethlehem, the reign of Caesar Augustus went on making the real geopolitical headlines. Trees grew, populations shifted, glaciers crept, geology happened, sidereal time rolled along, the expanding universe kept reaching outward.

But the Joseph of the Protevangelium had a vision, or walked into the middle of something: the lag between fulfilled time in the stable and normal time everywhere else. In the Church Dogmatics, Karl Barth takes note of this odd passage and points out that this is “what fulfilled time would look like if we were able to view it.” He goes on to say: “If in its perfect divine actuality fulfilled time is to be the one and only truly moved and moving time, then it does indeed mean suspension, the total relativising of all other time and of its apparently moved and moving content.” ( I:1, p. 116)

The strange image of stopped time made its way into Christian traditions in a variety of ways. It’s mostly not in the visual arts tradition, because by its nature it can’t be portrayed in a still image. All paintings are suspensions of real time, aren’t they?. But we become aware of the contrast between fulfilled time and normal time in the peace and stillness of Christmas itself. This is probably the legend that was far back in the mind of the author of Stille Nacht, or of other carols that celebrate the sacred silence surrounding the birth of Christ.