They called him by the Latin name Guilliamus Amesius, but if we talk about this British-born theologian at all now, we call him William Ames (1576-1633). Dust him off and read him. Here are some lessons I learned from Ames years ago that have stuck with me ever since.

They called him by the Latin name Guilliamus Amesius, but if we talk about this British-born theologian at all now, we call him William Ames (1576-1633). Dust him off and read him. Here are some lessons I learned from Ames years ago that have stuck with me ever since.

Ames was educated at Cambridge (Christ’s College) under William Perkins, “the architect of Elizabethan Puritanism.” Ames distinguished himself as a scholar and preacher, and appeared to have a promising career ahead of him. But because of his strict nonconformist beliefs, he found every chance for promotion blocked by anti-Puritan officials. Finally, under the persecutions of James I, Ames was forced to flee for his life to Holland. After moving from one position to another, he finally entered his most productive period of work when he was appointed professor at the University of Franeker from 1622-1633. Ames longed to move to the new world, but was never able to finance the trip. When he died, however, his wife and children came to America, bringing with them his library.

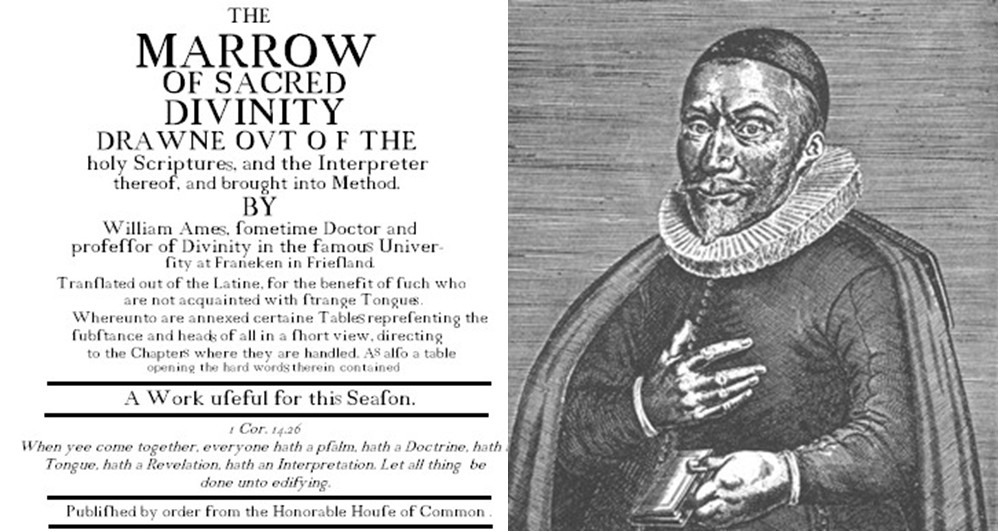

His books, especially his Marrow of Sacred Divinity, were very influential in America; the Marrow was used for years as a textbook of theology at Harvard and Yale. His work was an important part of the education of Jonathan Edwards, and Ames’ theology of the covenant was one of the most powerful influences on early American political thought. So Ames belonged to the British, to the Dutch, and to the Americans: he was a uniquely international theologian for the 1600s.

The theology of the seventeenth century was nothing if not polemical, and Ames was a man of his times, a theological fighter. He was an important advisor at the Synod of Dort (1618-1619), a firm five-point Calvinist committed to refuting the Remonstrants. He also wrote several books against Roman Catholic theology, and was especially engaged in debate with the Jesuits.

So Ames was not above getting into a good theological fight or two. But to his way of thinking, the proper business of theology lay elsewhere: in the upbuilding of the spiritual life. “Heretics,” he wrote in his Exhortation to Students of Theology, “have made controversial learning necessary to us, but God himself has committed to us, as an absolute necessity, the study of the religious life.” Our controversies are assigned to us by false teachers, but our real theological work is assigned to us by God. Both are necessary, but theology aimed at spiritual life is higher.

In his inaugural address at Franeker, he described his goal as a professor: “To see whether at least in our University I could in any way call theology away from questions and controversies, obscure, confused, and not very essential, and introduce it to life and practice so that students would begin to think seriously of conscience and its concerns.” He wanted to teach in such a way that lives were transformed. That led him to teach theology differently, and even to think about doctrine differently. He was definitely a systematizer, but what he systematized was an emphasis on spiritual experience. This was Ames’ contribution to theology in general: He was the first and greatest systematizer of the theology of pious experience.

Ames’ preferred method for systematizing was through a technique known as Ramist logic. This was a method based on the thought of Peter Ramus (Pierre de la Ramée, 1515-1572), a French Protestant philosopher whose goal had been to reform education along Renaissance humanist lines by organizing the principles of all the arts systematically. The Ramist approach to knowledge offered a place for everything and everything in its place. This was so appealing to the Puritan mind that “theological Ramism” became the style of the day. Ames was one of the most accomplished of the theological Ramists, and in his work he endeavored to bring theology into a clear systematic structure. His goal was to reduce it to its “heads,” or main categories, and to make its first principles evident, so that it could be more easily taught, learned, and memorized. Once the material of theology was thus “brought into method,” it could be put into practice. The highest praise for a Ramist theologian was that he made doctrine “methodical and useful.”

The standard Ramist way of doing this was to begin with the most general terms of a discipline, and to break them down analytically into their component parts. Each part could then in turn be analyzed, forming a kind of tree-like system of unified knowledge. This branching analysis, dividing each head into a pair of coupled components, was known as “dichotomizing.” When a subject had been dichotomized down to its finest points, every topic could be referred to its proper place within the whole. Ames had a real genius for this work, and he “dichotomized nearly everything he put his hands to, ” as Keith Sprunger wrote.

This medium was itself part of Ames’ message. Again in Sprunger’s words: “Well aware that he served a precise God, Ames created a precise theology.” Ames’ theology was a theology of the pious devotion of the heart, but in explicating it he was sequential, orderly, and structured; he gave the world a peculiarly left-brained Pietism.

Several interesting results show up in Ames’ theology, and we can see them in three related areas: What Ames has to say about the nature of theology, the nature of faith, and the nature of revelation. In each of these three areas, Ames stands out as the systematizer par excellence of the doctrine of the spiritual life, who demonstrated, in an age that was in danger of rigid, lifeless orthodoxy, that theology can and should be a stimulus to personal piety. But in each of the three areas, Ames also stands open to the charge that in pointing theology back towards its vital center in the heart, he went a little too far, shifting the basis of faith from God and his Word to inner, subjectivistic concerns and norms. How he kept his balance is crucial, and it’s what contemporary theology needs to learn from him.

The Nature of Theology

The first sentence of Ames’ Marrow of Sacred Divinity is remarkably pithy: “Theology is the doctrine or teaching of living to God.” (I.i.1) This definition may not sound radical to modern evangelical ears, but it was a sharp contrast to the “standard definition” of theology in orthodox protestant thought up to Ames’ time. The normal treatment was to describe theology as “wisdom concerning divine things,” sapientia rerum divinarum. That intellectual approach to theology made it possible to divorce pure doctrine from right conduct, as if the two were not necessarily related. Ames reunited the two by defining theology in less intellectualistic terms, replacing sapientia rerum divinarum with doctrina vivendi deo, “the teaching of living to God.”

Ames explained what he meant by “living to God:” “Men live to God when they live in accord with the will of God, to the glory of God, and with God working in them.” (I.i.6.) Thus, living to God means knowing and doing God’s will, and glorifying God, all with His power working in you. The intellectual element is not excluded from this definition, but it is relegated to being a means to an end, whereas in earlier orthodoxy it had often been considered an end in itself. For Ames, theology should really be called theozoia; living to God. (I.i.13)

In Ramist analysis, theology is to be dichotomized into two parts; faith and observance. (I.ii.1) This is because the principle behind the spiritual life is faith, and the working out of that principle is observance. (I.ii.2) It is important for Ames to emphasize that the principle, faith, comes first, and the actions, observance, flow out of it. (I.ii.5) In this way, Ames derives the two parts of theology from an analysis of “the spiritual life, which is the proper concern of theology.” (I.ii.2) Again, this is a different point of departure. The standard orthodox way of describing theology was as a cognitive discipline, taking its starting point with the analysis of propositional revelation. From such a beginning, the next step was to carefully determine the epistemic reliability of doctrines, and the Protstant Orthodox tradition followed this path with its long prolegomena.

Ames took a different starting-point, beginning theology on the spiritual reality available to the believer. From this beginning, the next step was to improve the spiritual life and conduct: “Each doctrine when sufficiently explained should immediately be applied to its use.” (I.xxxv.29) Ames’ followers among the New England Puritans followed this path.

The Nature of Faith

Ames defines faith as “the resting of the heart on God, the author of life and eternal salvation.” (I.iii.1) Compare this definition to that of John Calvin: “Faith is a firm and certain knowledge of God’s benevolence toward us, founded upon the truth of the freely given promise in Christ, both revealed to our minds and sealed upon our hearts through the Holy Spirit.” (Institutes III.2.7) Calvin’s definition is rich and multi-faceted; it carefully balances the heart with the mind. But the emphasis seems to fall on the cognitive terms: knowledge, truth, revealed, minds. It is not surprising then, that in the period following the Reformation, Protestant Scholastic thinkers developed this intellectual aspect of the Reformed idea of faith, at some times all but eclipsing the affective and volitional aspects. Faith came to be understood mainly, almost exclusively, as assensus, assent to revealed truth. Salvation by faith meant the acquisition by the mind of saving knowledge.

Ames’ definition called theology back to the meaning of faith for the entire person: acquiescentia cordis in deo, the resting of the heart on God. Faith is “an act of choice, an act of the whole man — which is by no means a mere act of the intellect.” (I.iii.3) Ames is willing to admit that there is such a thing as saving knowledge, but only if it “follows this act of the will and depends upon it.” (I.iii.4) Faith is basically a decision made by the heart, and only afterwards does it become knowledge held in the mind. By defining faith and theology the way he did, Ames was restoring a neglected side of the Reformation’s teaching; he “detoured contemporary Calvinistic orthodoxy and went back to Calvin himself,” according to Ernest Stoeffler (see The Rise of Evangelical Pietism, p. 135).

Revelation

Revelation, for the typical Protestant Orthodox theologian, was the first and most important topic of theology. Not so for Ames. He finally treats the topic of Scripture in Book I, Chapter 34 of the Marrow. His starting point, the spiritual life, kept him from getting around to a formal treatment of revelation until relatively late in his opening remarks. However, Ames is firmly committed to revelation, and it is not a subject ignored until Chapter 34; it is woven throughout the entire fabric of his theology. He proves every assertion by appealling to scripture, and he mentions revelation whenever his subject calls for it. For instance, in the Marrow I.iv, when he takes up the doctrine of God, “the object of faith,” he says that “God, as he is in himself, cannot be understood by any save himself,” (I.iv.2) but that we can know him “from the back, so to speak,” “as he has revealed himself to us.” (I.iv.3)

Ames sometimes sounds very modest about what we can know about God. In revealing himself, God has had to accommodate himself to our ability to understand: “Many things are spoken of God according to our own conceiving, rather than according to his real nature.” (I.iv.5) In a more strictly intellectualizing system, this attitude would chafe. But it is not a problem for Ames. His main concern is “living to God,” and God has revealed enough about himself to enable us to live to him. (I.iv.6)

Again, Ames is a conservative and biblical theologian, not an experiential-expressivist liberal. To see how fundamental revelation is to Ames’ system, we should notice how he uses it to support his first principles. Theology is the doctrine of living to God, he tells us in I.i.1. He immediately goes on to explain why theology is different from all other arts and sciences: “The basic principles of theology, though they may be advanced by study and industry, are not in us by nature.” (I.i.3) Theology, he makes clear, is “a discipline which derives not from nature and human inquiry like others, but from divine revelation and appointment.” (I.i.2)

What does it mean to start theology with the spiritual life, and then to qualify it in this way? It means, among other things, that “the spiritual life, which is the proper concern of theology” (I.ii.2), is not a self-positing and self-authenticating reality deserving of study for its own sake. The spiritual life is to be understood as an experiential reality which is what it is because of its conformity to God’s word. “All things necessary to salvation are contained in the Scriptures and also those things necessary for the instruction and edification of the church. Scripture is not a partial but a perfect rule of faith and morals.” (I.xxxiv.15-16) In studying the spiritual life, the life lived to God, the theologian is analyzing something which takes its shape and its content from the powerful guidance of Scripture. This basing of the Christian life in the revelation of God is what keeps Ames’ theology from veering into subjectivism. Ames can focus on Christian experience of God, and turn theology into the science of analyzing this pious experience, because he understands the word of God and the Christian life as being unified, the one causing the other. One scholar (Karl Reuter) has argued that in the period of Protestant Orthodoxy, “the unity of the Reformers’ theology was broken between the objectivity of Christian knowledge and the subjectivity of Christian experience,” and Ames recognized this and corrected it.

The marrow of Ames’ theology, it seems, lies in this rediscovered unity between the knowledge of God and the service of God. If the priority of the Word of God in forming Christian experience were lost, Ames’ theology would indeed slide into subjectivism and the relativism of pious feelings. This loss of a foundation is what happened in later German thought, especially with Schleiermacher, for whom religious intuition, divorced from revelation, became the first principle of a new theology. But it is wrong to see in Ames the beginning of this line of thought (Ames interpreters like Reuter and Otto Ritschl make this false move).

Ames’ legacy is not found among the liberal advocates of experience as the foundation of theology. It is to be found among the New England Puritans, who continued for some time to hold the Christian life and God’s word in the Scriptures together in the closest unity. And Ames’ approach to theology is still a valuable and viable option for American evangelical theology in our own day. His pragmatic temperament is very much in tune with our own, and his focus on living to God rather than gaining abstract knowledge about him sounds like the subtext of much evangelical preaching and writing. At the same time, the absolute necessity of letting Christian experience be formed and normed by the Scriptures is a word of caution to the contemporary church, which is certainly not immune from letting spiritual experiences become ends in themselves.