The word “lent” is of Anglo-Saxon origin and literally means “spring,” though the practice of observing a 40 day period of preparation for Easter goes back to the time of the early Church and was a fully developed liturgical season by the twelfth century. In short, Lent is our own imitation of Christ’s journey into the wilderness to be tempted by Satan – it is our own form of bearing the yoke of Christ and feeling pain and discomfort like that experienced by Christ as he faced temptation and deprivation. Further, it is a season in which we give ourselves over in particular to fasting and prayer, again in imitation of Jesus Christ. As the well-known Lenten hymn says, “The glory of these forty days we celebrate with songs of praise; for Christ, through whom all things were made, himself has fasted and has prayed… Then grant us, Lord, like [him] to be full oft in fast and prayer with thee.”

The nature of Lent is twofold: it is a season of preparation and it is an ascetical season. Regarding preparation, we prepare ourselves to weep on Good Friday as we remember, re-enact and reflect upon the death and burial of Jesus Christ. Lent affords us the space not to rush past the cross to the resurrection but, instead, to dwell, perhaps even uncomfortably, in our loss. The Savior has died so how will God’s salvific plan come to fruition? Like Abraham of old we are left to wonder how God’s promises will be fulfilled in the loss of the only-begotten Son.

We prepare ourselves to wait on Holy Saturday yet many of us do not wait well. Waiting is viewed as a waste of time and we eagerly fill up any waiting with phone conversations, emailing or social media. Yet, Lent is about waiting and no more so than on Holy Saturday. Christ has died yet we anticipate and await his resurrection. We are the disciples huddled together in fear. Christ had promised that “The Son of Man [will] be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him, and he will be raised on the third day” (Matt. 17:22-23). But, will it happen as promised? Holy Saturday reminds us that we will have to wait and see.

Lastly, we prepare ourselves to rejoice on Resurrection Sunday. Easter Sunday brings our hopes and fears to an end. Whereas we wept at Jesus’ death on Good Friday and hoped for his return on Holy Saturday, Easter Sunday brings all to fruition: “Good Christian men, rejoice and sing! Now is the triumph of our King! To all the world glad news we bring: alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! The Lord of life is risen today! Sing songs of praise along his way; let all the earth rejoice and say: alleluia, alleluia, alleluia!”

Lent is also an ascetical season and this is the focus that it most often receives in popular culture with the proverbial giving up of chocolate or coffee. But this giving up of things has a purpose. The word “ascetical” comes from the Greek word askesis and means exercise or effort. The purpose of asceticism is not just to make us uncomfortable or to free our spirit from its bodily entrapment. Rather, asceticism frees both the body and spirit from the passions; that is, from a state that is contrary to the divine purpose for being human, which is to be in communion with God. Asceticism assists in making us fully human, not less human. Our spiritual growth is a journey of us becoming what we were made to be – human beings in communion with God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. Ascetical endeavors assist us on the journey. They are means of grace.

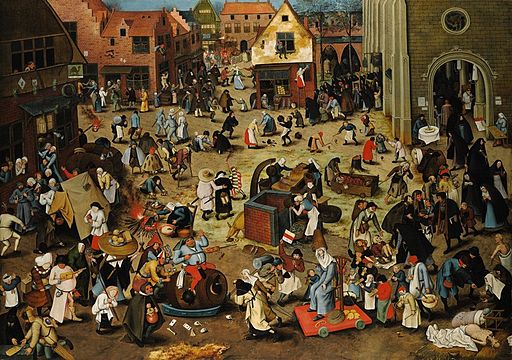

![Fra Angelico (circa 1395–1455) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Fra Angelico 031](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Fra_Angelico_031.jpg/256px-Fra_Angelico_031.jpg)

Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–543). Detail from a fresco by Fra Angelico (c. 1400–1455) in the Basilica San Marco, Florence.

Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century said, “The life of a monk ought to be a continuous Lent. Since few, however, have the strength for this, we urge the entire community during these days of Lent to keep its manner of life most pure and to wash away in this holy season the negligences of other times” (Rule of Benedict 49.1-3). Though Benedict directs these words to men living under his rule in a monastery, they seem applicable to all baptized believers since we too are called to live lives of holiness: “You shall be holy, for I am holy” (1 Peter 1:16). Yet, what are the means to wash away the negligences of other times? Benedict answers, “This we can do in a fitting manner by refusing to indulge evil habits and by devoting ourselves to prayer with tears, to reading, to compunction of heart and self-denial” (RB 49.4).

So, we can keep a good Lent by refusing to indulge evil habits. According to the Apostle Paul, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree with the law, that it is good. So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me” (Rom. 7:15-20). Our Christian lives are a struggle, a battle against “against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph. 6:12); therefore, we must “Put to death therefore what is earthly in [us]: sexual immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry. On account of these the wrath of God is coming. In these [we] once walked, when [we were] living in them. But now [we] must put them all away: anger, wrath, malice, slander, and obscene talk from your mouth. Do not lie to one another, seeing that [we] have put off the old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator” (Col. 3:5-10). Our life depends on our ability to die – to self and to sin. We do not do this merely be ascetical actions but they are an aid. It is ultimately God in us who puts sin to death. Though our Christian life is characterized by struggle we will gain the victory. Just as Jesus Christ conquered death so we will conquer sin.

We can also keep a good Lent by devoting ourselves to prayer with tears. Though we may not always pray with tears, we must always pray. Prayerful tears are indicative of our deep longing for God to do his work within us and are a sign of our grief due to sin. Our best response is to be like Christ: “In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to him who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverence” (Hebrews 5:7). During Lent we should also devote ourselves to reading, particularly the Scriptures, a sentiment that is not only Benedictine but Pauline: “Until I come, devote yourself to the public reading of Scripture, to exhortation, to teaching” (1 Tim. 4:13). Further, let us devote ourselves to compunction of heart: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted” (Matt. 5:4), mourning not only for our own sins but the sins of the whole world.

And finally, we should, during Lent, devote ourselves to self-denial by way of asceticism. The Apostle Paul admonishes us to “…train [ourselves] for godliness; for while bodily training is of some value, godliness is of value in every way, as it holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come” (1 Tim. 4:7b-8). And this is not just a taking away from our usual discipline but it is an adding something to it: “During these days, therefore, we will add to the usual measure of our service something by way of private prayer and abstinence from food or drink, so that each of us will have something above the assigned measure to offer God of his own will with the joy of the Holy Spirit (1 Thess. 1:6)” (RB 49.5-6). Not only do we not do things but we also take on an added measure of spiritual disciplines during Lent. Again, this ascetic tendency is in imitation of Christ, it is a bearing on my own body the marks of Jesus (cf. Gal. 6:17).

All of this activity sums up the purpose of Lent, which is to “look forward to holy Easter with joy and spiritual longing” (RB 19.7b). For Lent is about preparation, a looking forward to the events of Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday. We observe Lent so that Easter is not just a day on the calendar but a season in the Christian year. Such preparation and profundity is summed up well in George Herbert’s poem from 1633 simply entitled “Lent”:

Welcome deare feast of Lent: who loves not thee,

He loves not Temperance, or Authoritie,

But is compos’d of passion.

The Scriptures bid us fast; the Church sayes, now:

Give to thy Mother, what thou wouldst allow

To ev’ry Corporation.

The humble soul compos’d of love and fear

Begins at home, and layes the burden there,

When doctrines disagree.

He sayes, in things which use hath justly got,

I am a scandall to the Church, and not

The Church is so to me.

True Christians should be glad of an occasion

To use their temperance, seeking no evasion,

When good is seasonable;

Unlesse Authoritie, which should increase

The obligation in us, make it lesse,

And Power it self disable.

Besides the cleannesse of sweet abstinence,

Quick thoughts and motions at a small expense,

A face not fearing light:

Whereas in fulnesse there are sluttish fumes,

Sowre exhalations, and dishonest rheumes,

Revenging the delight.

Then those same pendant profits, which the spring

And Easter intimate, enlarge the thing,

And goodnesse of the deed.

Neither ought other mens abuse of Lent

Spoil the good use; lest by that argument

We forfeit all our Creed.

It’s true, we cannot reach Christ’s fortieth day;

Yet to go part of that religious way,

Is better than to rest:

We cannot reach our Savior’s purity;

Yet are bid, Be holy ev’n as he.

In both let’s do our best.

Who goeth in the way which Christ hath gone,

Is much more sure to meet with him, than one

That travelleth by-ways:

Perhaps my God, though he be far before,

May turn, and take me by the hand, and more

May strengthen my decays.

Yet Lord instruct us to improve our fast

By starving sin and taking such repast

As may our faults control:

That ev’ry man may revel at his door,

Not in his parlor; banqueting the poor,

And among those his soul.