“It’s the Bible that saves us!” Why do we talk that way?

“It’s the Bible that saves us!” Why do we talk that way?

Actually, I know why.

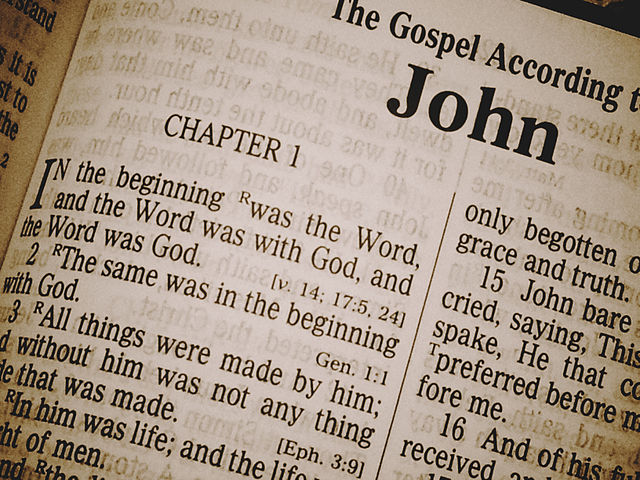

I recently heard a very good sermon about the Bible. It was based on Jesus’ story about the rich man and Lazarus, where the rich man begs to be allowed to return from his afterlife torment to warn his brothers what awaits them if they do not repent. Jesus’ storytelling is at its boldest here: he casts Father Abraham as a character, and writes dialogue for him! Abraham explains that the request is fruitless, because a warning from beyond the grave is worth far less than the Scriptures which the living brothers already know: “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.”

The preacher followed the thrust of this passage and led the congregation to a place where we had to confront the implications of Scripture as a message from God: how God uses it, how we should treat it, what we are to expect from it, and how much is at stake in its message. We have Moses and the Prophets, plus the Gospels and Epistles: Let us hear them!

After church, a small group met at my house, as usual, to eat, pray, discuss the sermon. A good passage and a good sermon and a good meal and a good group made for a good discussion, as usual. Small-group discussion always provides the chance to bring the sermon down into our own lives more intimately, and we especially talked about our need to get more and more of the message of the Bible into our minds and hearts so we could know and obey God better. We heard the sermon’s message loud and clear.

But a number of us registered something we had heard in several of the sentences that made up the sermon. These are not exact quotes, but the preacher kept saying things like “the Bible brings us salvation,” or “God has revealed himself in Scripture,” or “what changes lives is the word of God.” Our small group has been through a lot together, and it’s a high-trust environment, so several people felt free to admit candidly that those sentences seemed messed up: surely they put “the Bible” in exactly the place where we would expect to hear “Jesus” or “the Holy Spirit.” It sounded, in other words, like bibliolatry, like displacing God with a book, like skipping over Jesus himself and settling for a report about him. Farewell, Savior; hello Magic Book of Power!

And yet we all knew better than that. We know the preacher’s life, his character, and his doctrine, and we know he’s not in the least danger of substituting the Bible for God. In fact, while hearing the sermon, each of us was cutting the preacher some slack: some of us immediately in the very act of hearing, others only after reflection. But all of us knew he knew better, and probably knew he knew we knew he knew better. Because the whole church is a high-trust environment.

In fact, statements like “the Bible saves us” are not actually false claims, considered charitably and in context. They’re just a strong form of metonymy, which is the figure of speech (he intoned didactically, assuming a rather professorial air and warming to his subject) in which a part of something is used to refer to the whole. We use metonymy so fluently we don’t notice it, especially when talking about important or delicate matters, or when we’re trying to communicate concretely and vividly. If I say “my brother’s been hitting the bottle and sleeping around,” you know I’m not concerned about bottles or sleep. I’m worried about what was in the bottle, obviously, and the way it was being used in a whole destructive pattern of life. The actual glass bottle’s really the least of my worries, the most innocuous and innocent thing in the whole affair. Same for the “sleeping” in “sleeping around.” Same for “your butt” in “get your butt over here.” One simple and concrete part is being used as a vivid symbol for the entire manifold reality.

When a preacher says “the Bible saves us” or “God revealed himself through the Bible,” he’s using one single part to evoke the vast, manifold, expansive reality that it is part of. All of God’s sovereign will for salvation, all of God’s decisive actions the history of redemption, all of the incarnation and atonement, all the ministry of the Holy Spirit, all the witness of the prophets and apostles, all the testimony of the church around us, all of it: metonymically signified by “the Bible.”

Good preachers have always talked like this. Examples from the church fathers could be multiplied. But take as a striking example John Wesley, who could say in the preface to his Standard Sermons

I want to know one thing,—the way to heaven; how to land safe on that happy shore. God himself has condescended to teach me the way. For this very end He came from heaven. He hath written it down in a book. O give me that book! At any price, give me the book of God! I have it: here is knowledge enough for me.

Wesley leaves out a lot there; actually he leaves out the cross and resurrection, and barely waves his hand at proper trinitarian and christological ways of talking. He is focused on the business end of learning God’s way of salvation: “Give me that book!”

The only times this metonymic way of talking doesn’t function properly is when the high-trust environment is lacking. If you have reason, or think you have reason, to suspect that the preacher really does worship a book at the expense of the living God, you will hear every metonym differently.

But if you know yourself to be in a high-trust environment, you will hear it the right way. You’ll get it. The Bible [insert the material content of the entire biblical message here] saves us. We have Moses and the prophets and the preacher; let us hear them.