In a class on Matthew’s gospel, my students are learning how to hear the voice of Matthew the evangelist, to understand how he structures his arguments, how he tells his stories, and what his particular theological concerns are as he reports the words and actions of Jesus. After the initial rush of excitement about how much there is to learn from this gospel, we come to an awkward point.

Before studying each gospel in depth, you can hardly tell the four evangelists apart, and you get used to just having the story of Jesus times four. But as soon as you start to develop an ear for what is distinctively Matthean, Markan, Lukan, and Johannine –cool word alert!– you may suddenly get the feeling that your new skills are taking Jesus away from you, and replacing him with: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. “I used to have Jesus! Who took him away? Now all I have is Jesus according to Matthew, Jesus according to Mark, etc.”

There is no need to panic. First of all, you never had “just plain Jesus.” You have always had Jesus as the Holy Spirit sovereignly chose to make him known to you, in these four gospels. So you haven’t lost anything, except imprecise Bible reading. And that’s a good thing to lose.

Secondly, Jesus according to the four gospels is not four Jesi, as if Jesus could be pluralized, and Jesi were even a word. The New Testament shows the one Lord Jesus Christ, from four overlapping and interconnected angles. When we saturate ourselves in the study of one gospel, we increase our understanding of the one Lord Jesus Christ, from one of the inspired angles of approach.

Third, this growth from an undifferentiated, monophonic uniformity, to a complex, orchestral unity, is what happens whenever you take on a new mental skill, habit, or ability.

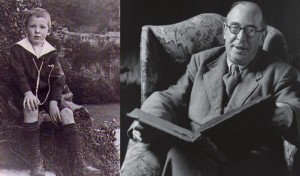

C.S. Lewis, master of illustrations, explains the process perfectly in the essay “Religion: Reality or Substitute?” He is making a different point, but his words are apt here:

When I was a boy, gramophone records were not nearly so good as they are now. In the old recording of an orchestral piece you could hardly hear the separate instrument at all, but only a single undifferentiated sound. That was the sort of music I grew up on.

And when, at a somewhat later age, I began to hear real orchestras, I was actually disappointed with them, just because you didn’t get that single sound.

What one got in a concert room seemed to me to lack the unity I had grown to expect, to be not an orchestra but merely a number of individual musicians on the same platform. In fact, I felt it “wasn’t the Real Thing.”

You may feel a pang of nostalgia and a desire to go back to just plain Jesus. But you’ve got to catch yourself here: What’s real is the Jesus of the New Testament, the Jesus of the four evangelists. What’s vague and imprecise is any other way of thinking about Jesus, with various stories from various gospels all mingled together and probably mixed with film images, past sermons, and other post-biblical sources.

About listening to orchestral music, Lewis admits that “owing to my musical miseducation the reality appeared to be a substitute and the substitute a reality.” But he knew that the actual orchestra was better than the monophonic recording in which no distinct instruments could be heard. So he set about adjusting his ear, refining his sensibilities, and learning to love the reality more than the substitute. When we devoutly study one particular gospel, and learn to think like Matthew, we are doing the same thing.