I recently read The Pastor as Public Theologian by Kevin Vanhoozer and Owen Strachan in which they rightly recognize that the role of the pastor-theologian has gone by the wayside, replaced, for example, by the pastor-CEO, pastor-therapist and/or pastor-social activist. Should pastors be all of these things? Sure, but not primarily. First and foremost pastors are shepherds of God’s flock, examples of holiness and faithfulness to the Church and to the world at large. In the words of Vanhoozer (quoting Lesslie Newbigin), “Stated simply: the pastor’s task is to help congregations ‘to become what they are called to be’” (p. 21). Unfortunately, it is the “called to be” clause that is so often misunderstood, both by pastors themselves and frequently by the very sheep that they are called to shepherd.

I recently read The Pastor as Public Theologian by Kevin Vanhoozer and Owen Strachan in which they rightly recognize that the role of the pastor-theologian has gone by the wayside, replaced, for example, by the pastor-CEO, pastor-therapist and/or pastor-social activist. Should pastors be all of these things? Sure, but not primarily. First and foremost pastors are shepherds of God’s flock, examples of holiness and faithfulness to the Church and to the world at large. In the words of Vanhoozer (quoting Lesslie Newbigin), “Stated simply: the pastor’s task is to help congregations ‘to become what they are called to be’” (p. 21). Unfortunately, it is the “called to be” clause that is so often misunderstood, both by pastors themselves and frequently by the very sheep that they are called to shepherd.

Without repeating what is said in The Pastor as Public Theologian (which deserves to be read by most Christians, pastors and laity alike), one of these areas of misunderstanding is that the pastor is supposed to love everyone in such a way that they never speak in a manner that hurts the parishioner’s feelings. That is, pastors are viewed more as little-league coaches who are expected to treat the players on his team as equals despite their level of ability; or as teachers who are supposed to pass everyone no matter how right or wrong their math answers might be. We lament the fact that teachers pass poor readers to the next grade level but we find it unconscionable that they would actually tell a 10th grader and his parents that he is reading on a 4th grade level. That’s critical and criticism is harsh and counter-productive; or, that, at least, is the prevalent narrative in today’s “we’re all the same” mindset. (Except, it appears, in the matter of race where we are all radically different so as to capitalize on various narratives appropriate to our skin color).

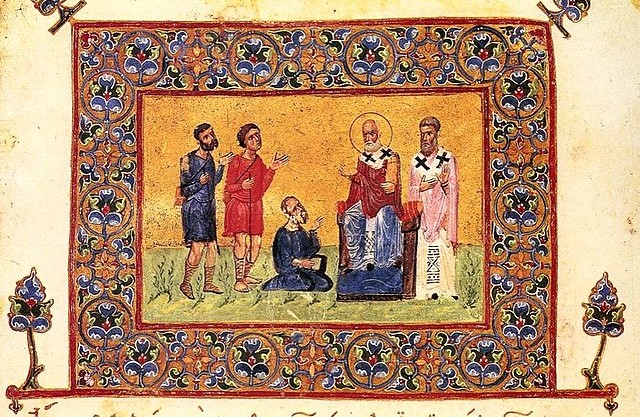

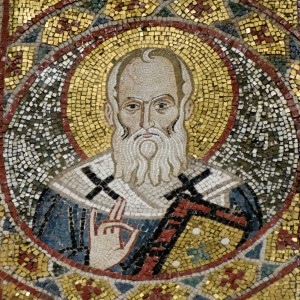

Yet, this is a naïve perspective of pastoral ministry and one that is not shared with the earlier Christian tradition. Some of the church’s most profound theologians (e.g., John Chrysostom [d. 407] and Gregory the Great [d. 604]) also wrote influential treatises on pastoral ministry. John Chrysostom wrote Six Books on the Priesthood and Gregory the Great wrote his popular, perhaps even infamous, Book of Pastoral Rule. These treatises exercised a profound influence in their time, throughout the Middle Ages and have even come back into fashion in the twenty-first century. (See, for example, Andrew Purves, Pastoral Theology in the Classical Tradition). Another important early Christian voice on pastoral ministry is Gregory of Nazianzus (d. 390), one time bishop of Nazianzus and later Archbishop of Constantinople. Gregory, despite being ordained a priest and consecrated a bishop “not by [his] own will, but by the coercion of others,” was an effective and attentive pastor to his flocks. His approach to pastoral ministry was upfront and pragmatic. Unlike many pastors and laity today, Gregory knew that pastoral ministry would, on occasion, require a love that was not sentimental or necessarily gentle. In his Second Oration he writes,

In some cases it is necessary that the pastor show anger in the interest of love, or seem to despair of a parishioner as if a hopeless case, even though from another perspective he is far from hopeless. Each pastoral response hinges strongly on the particular temperament of the person. Some we must treat with meekness in order to encourage them to a better hope. Others seem to require that we combat and conquer them and never yield an inch. The pastoral principle: variability. All persons are not to be treated in the same way. We do not simply say this is virtue and this is vice uncontextually. For one spiritual remedy may prove dangerous in some cases and wholesome in other cases. The right medicine must be applied for the right occasion as the temper of the patient allows and as the time and circumstance and disposition of the individual indicate. This, of course, is the most difficult aspect of pastoral wisdom, to know how to distinguish which counsel is needed in which situation with a precise judgment so as to administer appropriate remedies for different temperaments. Only actual experience and practice are the basis for skillfully applying this art. (Oration II.30-33)

My guess is that such a statement would not go over well these days with a pastoral search committee: “he’s too harsh,” “we need someone who will shepherd our flock gently” or “clearly he does not care about people” would be unsurprising responses to Gregory’s forthrightness and wise pastoral counsel. To be fair, however, there are many churches that would gladly hire someone of this caliber and honesty, though I would guess that those congregations are in the minority.

Gregory’s premise here is that pastoral ministry and, consequently, how a pastor relates to each person in his congregation differs. That is, there are as many different pastoral responses to people as there are people. He calls this pastoral principle “variability” and it is this that our contemporary church would do well to rediscover. Having pastored for over twenty years at five different churches I have met both the hopeless parishioner and the far from hopeless. I have met the meek parishioner and the combative conqueror. My mistake for too many years was to handle the combative conquering member of my parish with gloves that were too soft. What they needed was a medicine that I was not giving them. I had been taught (either explicitly or implicitly, I don’t recall) that pastors must always be gentle and soft but Gregory (and personal experience) have taught me that this is not the case. There are actually Christians out there whose behavior is not only detrimental to himself but to the larger Church of God; therefore, the remedy applied by the pastor must be appropriate to the malady. And sometimes that involves firmness and a resolve that is perceived to be less than loving even though it is motivated by a love appropriate to the person and to the situation.

Yet, Gregory is right to recognize that all of this takes wisdom and I would suggest that it may even be a kind of wisdom that is beyond a pastor’s experience even though, says Gregory, it only comes about through experience. And this is where it is important for pastors not to operate alone but to rely on the wisdom of other pastors and godly leaders. I feel fortunate as an Anglican priest to have a bishop over me who helps to guide and direct me through difficult pastoral moments. His years of experience and wisdom give him an insight into those whom I pastor that I often lack. His oversight provides appropriate accountability in difficult circumstances so that I am not acting out of my own weaknesses and frustrations. He can help understand the context so as to give guidance on how to “administer appropriate remedies.” Nonetheless, I need to have these experiences, Gregory would say, because it is only by these experiences that I am gaining the wisdom necessary to pastor well. So, I must not attempt to avoid these difficult parishioners but, rather, see my experience with them as growth in wisdom – for me and, I trust, for them too. Turns out that to be a good pastor one must, well, pastor, albeit with wisdom.