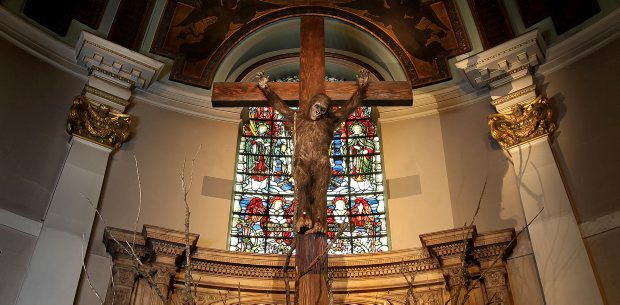

Paul Fryer’s striking art installation is a beautiful and realistic work… of a crucified gorilla. At first one might think his “Privilege of Dominion” is little more than a parody of the Christian faith, a repetition of ancient graffiti portraying Christ crucified with the head of a donkey. And in fact there has been some debate over whether Christians should take offense at this, with varying levels of insight into how non-Christians can and should interact with Christian beliefs and symbolism.

I, for one, am not at all inclined to take offense. Rather, I am enthralled with this image, having taken the artist at his word. As far as I understand, Paul Fryer sought to “highlight the plight of the Western Lowland Gorillas, and to challenge the Christian notion that animals do not have souls.” And of course those are great things to highlight and challenge. At the moment, however, I would like to point out a further dimension of Fryer’s piece: the question of whether Christ in any sense became a creature for the sake of creatures (Barth, Church Dogmatics III/1, p. 381)—a broader and more inclusive understanding of the incarnation. In other words, did Christ die for animals?

Biblical and theological balance and symmetry would seem to demand it. At a surface level, given the prominence of animals at creation (Gen. 1-3) and in the eschaton (Rev. 5:13-14), their absence would be conspicuous in the story of Christ and his passion. More significantly, the idea of atonement as re-creation and the bold claim of Col. 1:20 that God was pleased to reconcile all things to himself through the blood of the cross, whether on earth or in heaven, demands that we seek to develop “a doctrine of the atonement that follows the doctrine of the incarnation in encompassing all creatures” (Clough, On Animals, p. 105).

The key here is the passive role of the animals, who are oppressed and overwhelmed—for the dominant category seems to be that of a passive subjection to futility (Rom 8:20). Creation suffers and longs for the time of its freedom and glory—not because of its own sin, but because its fate is bound up with that of the children of God. Implicit within this understanding is a definite order, in which humankind is the key to creation and its well-being (Webb, On God and Dogs, pp. 175-8). Just as the narratives in Genesis 1-2 build toward the creation of humankind to tend and keep the garden, so it is the restoration of humankind that will result in the ultimate flourishing of that garden, for the fate of the two are bound together.

In the meantime, animals suffer under the consequence of human sin, both directly and indirectly. And while the pain and suffering may not be the result of the sin of animals, who are not generally held to be moral agents, it is nonetheless a concern to God, and one to be remedied by Christ’s death and resurrection, with emphasis on the latter (Webb, p. 167). Christ’s atoning work includes, though it is not limited to, redemption, and in this case it seems that “victims of sin need redemption rather than reconciliation: their victimhood does not separate them from God in a way that requires the work of Christ to overcome” (Clough, p. 120). That is to say, the victims of sin need rescuing from these circumstances, inasmuch as they are not part of an intentional conflict calling for reconciliation.

To put it simply, Christ’s death and resurrection affects the animal kingdom similarly to the way that it redeems our bodies from the plight of sin—by means of bearing the full consequences of evil, and then restoring creation in the resurrection, through which God makes all things new. Until that time, Romans suggests (8:18-25), creation must continue to wait in its pains of childbirth—a waiting that includes ignorance as to the manner or extent of the resurrection of individual creatures.

All creation suffers with Christ, but the suffering of Christ is different from that of his creation for it is vicarious and specifically human. The Creator takes the form of a creature, that in himself he might bear the suffering and plight of creation, restoring creation to its proper glory and flourishing in his resurrection.

Is it in some sense proper to portray Christ crucified as a gorilla? I would side with Fryer, not because Jesus was a gorilla or some other animal, but because the fate of creation itself, and including the Western Lowland Gorillas, is bound up in the death and resurrection of Jesus—God’s work to restore creation to its intended fullness.

For more on this topic, and the impact of Christ’s death and resurrection on the whole of God’s creation (including, but not limited to, humankind), please see my forthcoming book, Atonement: A Guide for the Perplexed.