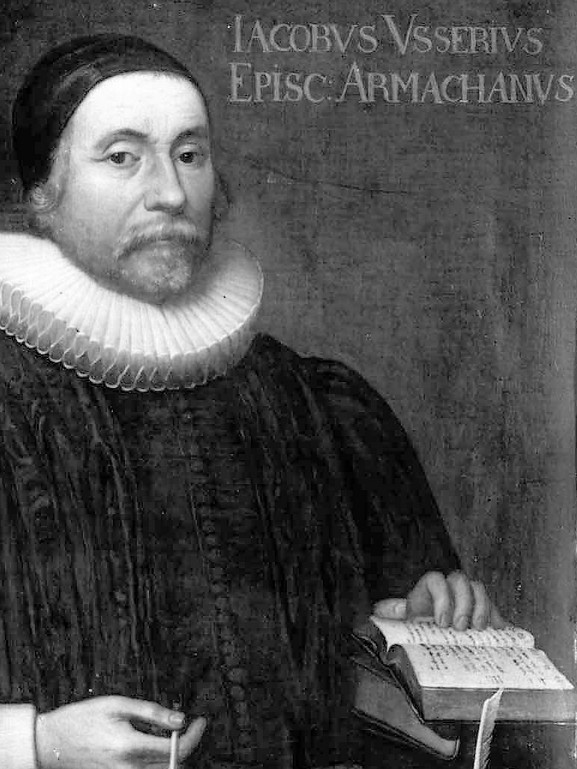

The discussion of personhood in James Ussher’s 1648 systematic theology (A Body of Divinity: The Sum and Substance of the Christian Religion) is brief, and interesting on several counts.

The discussion of personhood in James Ussher’s 1648 systematic theology (A Body of Divinity: The Sum and Substance of the Christian Religion) is brief, and interesting on several counts.

Ussher divides the discussion into two parts: Persons in general, “and then what a Person in the Trinity is.” Along the way he picks up some Christological considerations as well.

The Body of Divinity is presented in question-and-answer format. Here is the relevant section:

For the better understanding of this Mystery, declare unto me what a Person is in general, and then what a Person in the Trinity is.

In general, a Person is one particular Thing, Indivisible, Incommunicable, Living, Reasonable, subsisting in it self, not having part of another.

Wait, slow down a little bit! Can you, like, show me the reason of the particular branches of that definition?

Show me the reason of the particular Branches of this Definition.

I say that a Person is, first, one particular Thing: Because no general Notion is a Person. Secondly, indivisible: Because a Person may not be divided into many Persons; although he may be divided into many parts. Thirdly, incommunicable: Because, though one may communicate his Nature with one, he cannot communicate his Person-ship with another. Fourthly, living and Reasonable: Because no dead or unreasonable thing can be a Person. Fifthly, subsisting in it self: To exclude the humanity of Christ from being a Person. Sixthly, not having part of another: To exclude the Soul of Man separated from the Body, from being a Person.

“Thing” is not exactly a technical term in English, but the key word here seems to be “particular,” since what is to be excluded is anything general. “Incommunicable” is interesting to ponder, as when I ask my students if they would accept the bargain that they could live forever as long as they agreed to be me while doing so. This sort of incommunicability is at the heart of the mystery of personhood.

But it’s the fifth and sixth branches that seem strikingly ad hoc, in a good way. Fifth: a person must be said to subsist in itself, because otherwise the human nature of Christ would be a person and Nestorianism would be true. The human nature of Christ, we recall, came into existence in order to be the human nature of the second person of the Trinity. It isn’t personal, or hypostatic, in itself; there was no Mr. Jesus, swiped from his mother Mary, who turned out to be the Son of God. There was the Son of God who took human nature to himself and made that one particular instance of human nature his own body and soul, being himself in and as it.

And sixth: we have to define a person as “not having part of another,” because otherwise when the soul of a human is separated from the body, that soul would be a person. Now I have to confess I’ve never pondered it this way before. I believe in soulish existence in the intermediate state, but I would have called that soulish entity something like a naked person, a temporarily unembodied soul. It seems that Ussher wants to deny its personhood, saving the term “Person” for the body-soul totality. Or perhaps I’m reading this wrong.

In both of these cases, Ussher writes as if he has inserted an element into the definition of person just to make room for special cases like the (utterly unique) incarnation and the (common but not normal) intermediate state. I suppose his way of talking is probably shorthand; he’s gesturing to the clearest cases that support his definition rather than to the cases that required him to make exceptions. But still it indicates a flexibility and a willingness to take in evidence from purely revealed, theological sources. That matters a lot when his overall approach is to throw the term “person” over realities human and divine. Human personhood and divine personhood must be analogically related, but it would be surprising if they were univocally related, if “person” meant in God precisely what it means among humans.

So then,

What is Person in the Trinity?

It is whole God, not simply or absolutely considered, but by way of some personal Properties. It is a manner of being in the Godhead, or a distinct Subsistence (not a Quality, as some have wickedly imagined: For no Quality can cleave to the Godhead) having the whole Godhead in it, John 11:22. and 14.9, 16. and 15.1. and 17.21. Col. 2.3,9.

“Whole God,” to use the terse 17th-century locution, considered by way of personal properties. “A distinct Subsistence… having the whole Godhead in it.” Not one third of God, but God. Not God considered absolutely or without regard for inner relations, but considered in those relations.

In what respect are they called Persons?

Because they have proper things to distinguish them.

Proper things? Like what? How do you make that distinction?

How is this distinction made?

It is not in nature, but in relation and order.

Again, not with regard to divinity considered absolutely, but with regard to inner relation and order.

The next few questions and answers turn to taxis and relations of origin within the godhead; this is the foundation of personhood in God and the place where the analogical interval between persons human and divine expands beyond the field of our vision. But the word, carefully defined and flexibly handled, still seems to function to enable meaningful speech about God.