Polanus’ eighteen Axioms on the Trinity are mostly pretty short, but Axiom 14 stands out for its length and comprehensiveness. It’s as long as the other seventeen put together (3,000 words out of the total 6,000), and it covers a lot of ground. It will take several episodes to get through, but some of Polanus’ best work is here in the details of this axiom, so it repays close study and leisurely discussion.

In this first part, Polanus has a very helpful account of what it means to call a person of the Trinity autotheos (something like “God from himself”), and why each of them can be called so. In connection with his, Polanus also gives a good account of what we might call the essential self-sufficiency of each person considered not in relation to the other persons, but just as being a divine person under the concept of the divine essence. Finally, we get to see in some detail how the doctrine of divine simplicity serves the doctrine of the Trinity: not just that the two doctrines don’t conflict with each other, but that simplicity really helps account for triunity.

We will only be publishing a little bit of Axiom 14 at a time; just the part we’re talking through. So here is the translation, followed by the discussion and notes:

Axiom 14. One can consider any divine person either commonly/in common, or individually. I.e., each person is said to be God either under the concept of the common essence or under the concept of the individual person.

Thinking commonly, then, one can consider each person in the essence as he is God. The divine essence does not have existence in the Son and Holy Spirit that is other than its existence in the Father, because the essence and divine existence do not differ. Rather, all persons of the deity subsist in one and the same essence.

Considering each singularly, one can also think about a person in two ways: absolutely or relatively.

Take the person first absolutely, in himself or where he is with respect to himself, i.e. according to his nature as he is God and according to his act of subsisting whereby he subsists in himself and through himself. In that way, the person considered with respect to himself is αυτοθεος: God having the divine essence which exists from the essence itself and through itself and not from another essence or through another essence. Thus, one says the Father is wise with respect to himself, not with respect to the Son; he is wise not from that wisdom whom he begets. And one says the Holy Spirit is wise not from the Son, whom one says is the wisdom of the Father—the Holy Spirit is wise with respect to himself, because the Holy Spirit is God, and in God “being wise” is the same as “being God.”

Here’s the conversation:

Show notes:

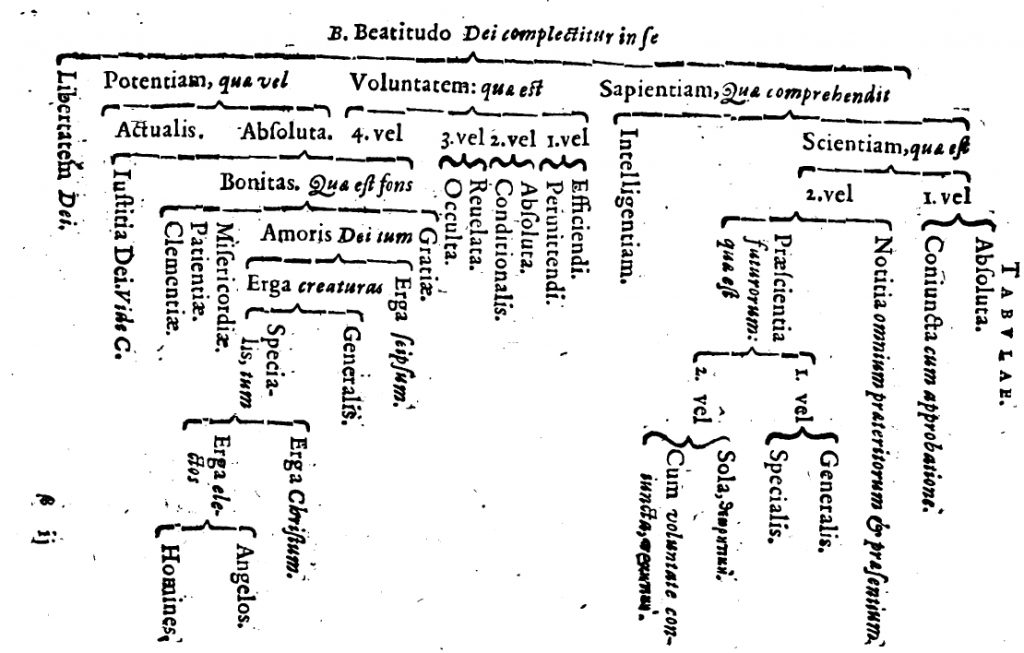

Polanus makes distinctions, and then distinctions within those distinctions, and so on; He loves a good Ramist chart. In his Partitiones Theologicae (the Divisions of Theology), he actually published dozens of them. Here’s my favorite, the one on divine blessedness:

Oooh, that’s good stuff. And Polanus did a lot of it.

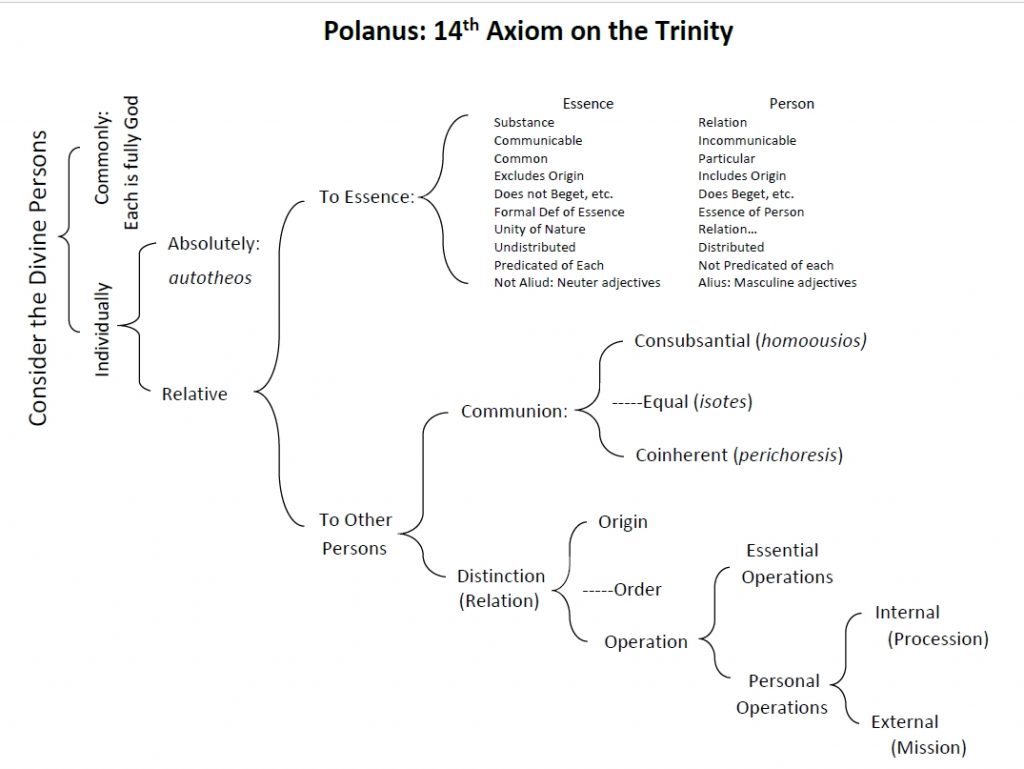

Axiom 14 is obviously that same kind of Partitiones-style nested series of distinctions, so even though Polanus doesn’t provide the visual aid here in his Syntagma, I drew it out in the same style:

This is the structure of the whole Axiom, though in this episode we only talk about the first couple of brackets (down to the word autotheos). Everything from the distinction labelled “relative” on down to the missions (at the bottom right) is for future episodes.

In upcoming episodes, we’ll refer to this chart a few more times. I’ll show it on the video now and then, but if you’re following along you’ll probably want the chart in front of you. It really is a very helpful organizational tool. Also, warning: I may update the chart as our discussion brings about fuller understanding of it. I won’t come back and fix this post, though; we’ll move forward and post an improved version in a later post.