My drawing teacher, Dale Leys, has recently been the subject of a forty-year, three-gallery retrospective exhibit. And while I couldn’t go to Kentucky to see the shows, I was thrilled to see that Kentucky’s public television channel, KET, aired a 30-minute documentary about his work (see below). I’ve had some great teachers since college, but none have quite measured up to Dale Leys.

My drawing teacher, Dale Leys, has recently been the subject of a forty-year, three-gallery retrospective exhibit. And while I couldn’t go to Kentucky to see the shows, I was thrilled to see that Kentucky’s public television channel, KET, aired a 30-minute documentary about his work (see below). I’ve had some great teachers since college, but none have quite measured up to Dale Leys.

I majored in studio art at Murray State University in the late 80s, with a concentration in drawing. Dale was my academic advisor. He gave me a good scolding when I skipped a class meeting, and I never skipped another (drawing) class, even though they were so dreadfully early in the morning. He also gave me a C in drawing 101 and told me to “get out of art,” and that’s a direct quote.

Things got better from there, partly because I got better. It took me most of the first year to get any traction on learning how to draw, but almost as soon as I came under Dale’s instruction, I began to learn how to see. When my hand caught up with my eye, I got better grades and (more importantly) started making better drawings. But learning to see right down into the form and structure and texture and tone of the world, that was the main thing I needed and the main thing Dale taught. I had barely looked at a tree before Dale showed me how.

How did Dale –no, how does Dale, because he’s still teaching– teach students how to see, and then how to draw? His bag of tricks is probably pretty standard fare for drawing instructors: long lab sessions, still life and human figure in the studio, a lot of verbal coaching. He would arrange objects to catch the light instructively, give advice about materials, hold up colored sheets beside a model to dramatize the way ambient color affects the objects themselves, and so on. Dale is especially gifted at describing and re-describing the drawing process. I remember him circling the room saying “draw with your whole body,” “don’t look at where the model is, look at where he’s not,” “pretend you’re not putting pigment on a page, but you’ve got a powerful magnetic wand and you’re using it to pull a dark stain up through the page from beneath it,” “don’t think of yourself as standing in gravity, but as floating in a transparent medium; swim at the page through it,” “you’ve got ten thousand bad drawings in you, and they all have to come out before the good ones can get through.” It always sounded a little crazy, but it also made a lot of sense as an interpretation of the craft.

How did Dale –no, how does Dale, because he’s still teaching– teach students how to see, and then how to draw? His bag of tricks is probably pretty standard fare for drawing instructors: long lab sessions, still life and human figure in the studio, a lot of verbal coaching. He would arrange objects to catch the light instructively, give advice about materials, hold up colored sheets beside a model to dramatize the way ambient color affects the objects themselves, and so on. Dale is especially gifted at describing and re-describing the drawing process. I remember him circling the room saying “draw with your whole body,” “don’t look at where the model is, look at where he’s not,” “pretend you’re not putting pigment on a page, but you’ve got a powerful magnetic wand and you’re using it to pull a dark stain up through the page from beneath it,” “don’t think of yourself as standing in gravity, but as floating in a transparent medium; swim at the page through it,” “you’ve got ten thousand bad drawings in you, and they all have to come out before the good ones can get through.” It always sounded a little crazy, but it also made a lot of sense as an interpretation of the craft.

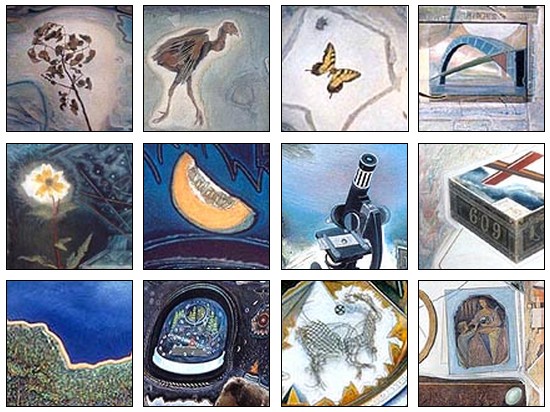

But what this documentary reminds me of is that so much of what Dale teaches he teaches by example. He lives his art. For forty years he has given his attention to making drawings. You can see great photos of his art at his website (the ones from the 80s and 90s are my sentimental favorites), and each image is so well composed that they communicate even online. But you really need to see them in person, because there’s a subtlety, complexity, and physicality that is only available if you’re in their actual presence.

But what this documentary reminds me of is that so much of what Dale teaches he teaches by example. He lives his art. For forty years he has given his attention to making drawings. You can see great photos of his art at his website (the ones from the 80s and 90s are my sentimental favorites), and each image is so well composed that they communicate even online. But you really need to see them in person, because there’s a subtlety, complexity, and physicality that is only available if you’re in their actual presence.

As triggers of recollection, these drawings work better for me than a college yearbook would; they are time capsules on par with any madeleine from Proust. Partly that’s because I’m nearly a quarter century out of college and am telescoping those years into seeing drawings that are old friends (“Hey, it’s that one chicken! Wow, is this 1988?”), but partly it’s owing to the nature of Dale’s work. His drawings are documents of time’s passage, concretizations of the process of their production. He layers natural forms into strange spaces, landscapes without horizons. So whatever else a particular drawing may be about, they’re all about time, space, and perception in a way that can’t be said of all visual art. As Dale says in the interview, “we see these things because we’re not very very small and we’re not very very large and so time-space flattens out, and that interests me, and so when I draw I think about that, so when I’m drawing a straight line I’m very deliberate about that.”

I did eventually take Dale’s advice and get out of art, but not until I’d accomplished a few things, made some good art after all, and been changed by my four-year apprenticeship in drawing. I got into theology, and I work a lot more with words now than with images. Sometimes I wish I’d had a four-year head start on theology instead of spending thousands of hours drawing, but my time in the art major doesn’t seem wasted. For one thing, I wasn’t getting a well-rounded liberal arts education at the state university, but I dove deep into studio art, and that put me in touch with critical rigor and concrete reality. There were standards to meet, and that made real progress possible (not something you can take for granted in all university humanities classes). I thought they were my own standards, and since I had internalized them so thoroughly, they sort of were. But viewing this documentary has reminded me that they were Dale’s first, in the particular form I picked them up in: his intensity, his work ethic and his delight in productivity, his searching criticism, his ability to think very slowly, meditatively, repetitively. Every time I crop the edge off of an image, I hear a Dale-like voice in my head asking, “Why cut it there? Why not half an inch to the left? Why not crop the other side instead?”

I did eventually take Dale’s advice and get out of art, but not until I’d accomplished a few things, made some good art after all, and been changed by my four-year apprenticeship in drawing. I got into theology, and I work a lot more with words now than with images. Sometimes I wish I’d had a four-year head start on theology instead of spending thousands of hours drawing, but my time in the art major doesn’t seem wasted. For one thing, I wasn’t getting a well-rounded liberal arts education at the state university, but I dove deep into studio art, and that put me in touch with critical rigor and concrete reality. There were standards to meet, and that made real progress possible (not something you can take for granted in all university humanities classes). I thought they were my own standards, and since I had internalized them so thoroughly, they sort of were. But viewing this documentary has reminded me that they were Dale’s first, in the particular form I picked them up in: his intensity, his work ethic and his delight in productivity, his searching criticism, his ability to think very slowly, meditatively, repetitively. Every time I crop the edge off of an image, I hear a Dale-like voice in my head asking, “Why cut it there? Why not half an inch to the left? Why not crop the other side instead?”

Dale’s powers of association work some sort of combinatory magic, intuiting deep connections between objects and objects, objects and ideas, objects and the media in which they are rendered, objects and the totality of what is. I don’t remember Dale ever saying he was “finishing a drawing;” he spoke instead, in hushed tones, about “finding closure.”

One more memory. Dale’s critiques are legendary, whether group or individual –in the documentary, a former student who was a classmate of mine recalls crying during a 101 crit. He would point to a color and ask why I was satisfied with exactly that color (“surely it’s not because the art supply factory just happened to manufacture a pastel in exactly the shade you would later come along and need?”), why exactly that line (“surely it doesn’t curve downward toward the right side because you ran out of energy and your wrist drooped?”), why exactly that amount of space (“if it went past the edge of the shape, what possible reason do you have for ever stopping it anywhere?”), exactly that decision (“if your horizon line isn’t doing any work for you, fire it”). In one critique, he was several questions into interrogating me about something weird that a lot of my ink-brush lines were doing, which I couldn’t give a good explanation for. In fact, I hadn’t even noticed that they were doing it until he pointed it out. With growing intensity, he kept asking, “you really don’t know why they do that?” “You don’t have a reason for them doing that?” “If you saw lines like these in another drawing, you wouldn’t notice or recognize them?” “You’re not trying anything with these?” “There’s literally not a thought in your head about this characteristic of these lines?” When I finally persuaded him that he had put far more thought into those lines than I ever had, he took out a small notebook and wrote something down. “Good,” he said. “Those lines are mine now. I’m going to use them for something. Unless you understand them, and then you can have them back.” I never did figure out what those lines were doing in my drawing; I had generated them accidentally while working on another technical aspect of the drawing. But later on I saw a couple of them in one of Dale’s drawings, and they really worked. He really did own them, by dint of comprehension.

One more memory. Dale’s critiques are legendary, whether group or individual –in the documentary, a former student who was a classmate of mine recalls crying during a 101 crit. He would point to a color and ask why I was satisfied with exactly that color (“surely it’s not because the art supply factory just happened to manufacture a pastel in exactly the shade you would later come along and need?”), why exactly that line (“surely it doesn’t curve downward toward the right side because you ran out of energy and your wrist drooped?”), why exactly that amount of space (“if it went past the edge of the shape, what possible reason do you have for ever stopping it anywhere?”), exactly that decision (“if your horizon line isn’t doing any work for you, fire it”). In one critique, he was several questions into interrogating me about something weird that a lot of my ink-brush lines were doing, which I couldn’t give a good explanation for. In fact, I hadn’t even noticed that they were doing it until he pointed it out. With growing intensity, he kept asking, “you really don’t know why they do that?” “You don’t have a reason for them doing that?” “If you saw lines like these in another drawing, you wouldn’t notice or recognize them?” “You’re not trying anything with these?” “There’s literally not a thought in your head about this characteristic of these lines?” When I finally persuaded him that he had put far more thought into those lines than I ever had, he took out a small notebook and wrote something down. “Good,” he said. “Those lines are mine now. I’m going to use them for something. Unless you understand them, and then you can have them back.” I never did figure out what those lines were doing in my drawing; I had generated them accidentally while working on another technical aspect of the drawing. But later on I saw a couple of them in one of Dale’s drawings, and they really worked. He really did own them, by dint of comprehension.

Here is the KET documentary, if you’d like to spend a little time meeting a remarkable artist in western Kentucky. You can tell from the respect with which his colleagues (my painting teacher Bob Head, and basic design guru Jerry Speight) speak of him that Dale Leys is an unusually powerful artist, and a singular teacher.

(If you want even more, these interviews also have some gems)