PBS’s American Experience did a show last year on Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944), the Pentecostal evangelist so archetypal that her whole life read like a movie script. The PBS documentary movie was surprisingly good, featuring interviews with most of the leading scholars responsible for major publications on McPherson in the past decade (Edith Blumhofer, Anthea Butler, Daniel Mark Epstein, and Matthew Sutton), and an even-handed account of McPherson’s life and ministry. TV documentaries rely too heavily on that dreadful re-enactment footage (soft focus, weird camera angles that don’t show faces, etc.), but this one also included a good amount of actual footage of McPherson preaching and singing. That footage was fascinating, even for people not normally susceptible to celebrity charisma.

PBS’s American Experience did a show last year on Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944), the Pentecostal evangelist so archetypal that her whole life read like a movie script. The PBS documentary movie was surprisingly good, featuring interviews with most of the leading scholars responsible for major publications on McPherson in the past decade (Edith Blumhofer, Anthea Butler, Daniel Mark Epstein, and Matthew Sutton), and an even-handed account of McPherson’s life and ministry. TV documentaries rely too heavily on that dreadful re-enactment footage (soft focus, weird camera angles that don’t show faces, etc.), but this one also included a good amount of actual footage of McPherson preaching and singing. That footage was fascinating, even for people not normally susceptible to celebrity charisma.

I grew up in a Foursquare Church, the denomination founded by McPherson. But I never remember hearing her name spoken. Partly that must have been because we were an upwardly-mobile congregation eager to downplay the eccentricities associated with mid-century Pentecostalism. But it might also have been a holdover from the scandal that demoted Aimee Semple McPherson to second-tier fame in the later phase of her ministry.

I grew up in a Foursquare Church, the denomination founded by McPherson. But I never remember hearing her name spoken. Partly that must have been because we were an upwardly-mobile congregation eager to downplay the eccentricities associated with mid-century Pentecostalism. But it might also have been a holdover from the scandal that demoted Aimee Semple McPherson to second-tier fame in the later phase of her ministry.

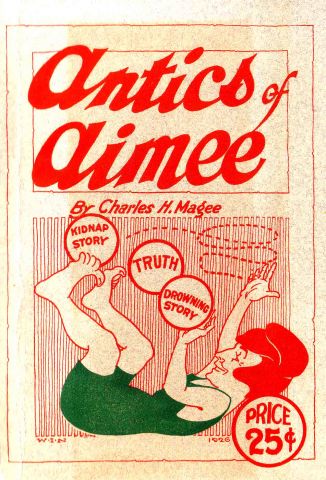

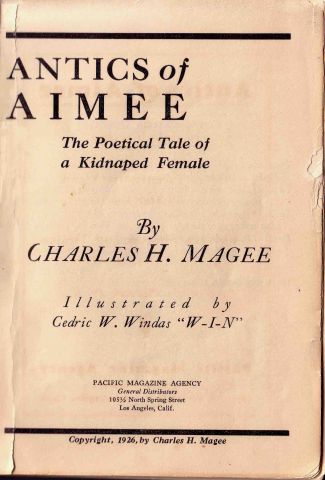

It was the 1926 disappearance or kidnapping scandal that cast a shadow over the reputation of McPherson. The story’s well known, but I recently came across a strange little artifact of it. It’s a self-published book from 1926 called The Antics of Aimee, by Charles H. Magee. Magee’s book is 64 pages of doggerel verse illustrated with a few cartoons, making fun of McPherson’s unlikely account of her kidnapping. The opening is typical:

I will tell you a story, now age-old and hoary,

Engraved on the pages of time,

And one that is known not around us alone,

But in many a country and clime.

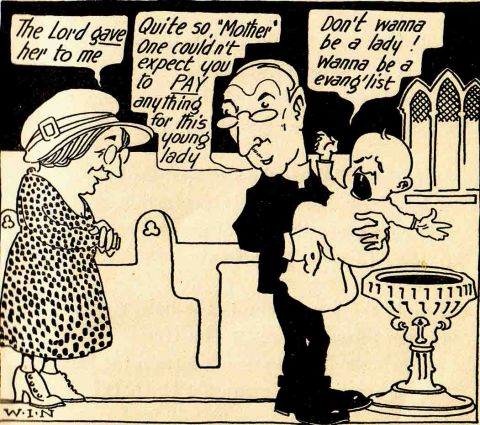

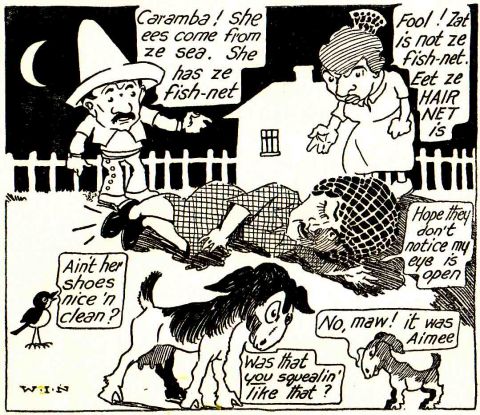

The poetry never gets much better or worse than that, but it does go on and on. And Magee seems determined to return to the same punch lines over and over: that Aimee’s a money grubbing glory-hound, that her followers are gullible and a little scary, that every detail of the kidnapping story is hilariously improbable, and that women shouldn’t be in charge of anything. The cartoons are a little more likable:

Although the cartoonist seems to be more at home with the editorial cartooning style, and gets himself into trouble when he tries to put too much narrative flow into one panel:

Aimee McPherson tried to defend herself against the accusations that she had engineered her own kidnapping, and gave sermons about how much she suffered from the slander. Magee, whose own religious views are hard to discern, pretends to take great umbrage at McPherson’s comparison of her own sufferings to biblical characters:

Oh, God! give me strength to condemn at full length

That person whose soul is so iced

That unblushing she’d dare her warped life to compare

To the life of the crucified Christ!

Magee ended up in court over his book, and while I doubt there was anything actionable about the book (aside from the crimes against meter which he commits repeatedly), it is a shame that McPherson gave Magee so much suspicious material to work with. Magee took full advantage of it to vent not only his misogyny and his suspicion of Mexicans, but also his indignation toward hypocrites.

The Antics of Aimee: I’d tell you to look for it in your local bookstore, but it is deservedly forgotten!