Robert Sokolowski has said that

The Christian God is presented as being so transcendent to the world that he could be, in undiminished goodness and greatness, even if the world were not. The Christian God can be distinguished from the world in this radical way. … In contrast, the gods of pagan religion and the first principles of pagan philosophers are gods and principles for the world and they could not be without the world.¹

In emphasizing the radical character the distinction between God and the world, Sokolowski draws attention to a contrast that runs so deep it is hard to communicate. The biblical God is not just transcendent, but “so transcendent that….”

It’s easy enough to put God on one side of the ledger of being, over against the world on the other side of the ledger. But pagan thought also did and does that: Homer with his Olympians looking down on the field of battle, Plato with his realm of ideas, and Aristotle with his first principles of the cosmos. All of them get to God from this side, and no matter how much they huff and puff about transcendence, they are still working with one pole of a God-world continuum. Even the people who insist there’s nothing but mystery at the other pole cannot escape this (in fact, they’re the worst offenders, but do be gentle when you break this news to them).

What Sokolowski calls the particularly Christian distinction goes further. It doesn’t just reason back from creation to a God who is necessary for the world, because in itself that chain of reasoning only shows a God who is this world’s necessary presupposition, which is to say, this-worldly in the sense of being the transcendentally necessary presupposition of the immanent. Something dyadic and mutual clings to causal arguments like this, unless they presuppose a deeper distinction between God and the world. God can exist without the world, but the world cannot exist without God.

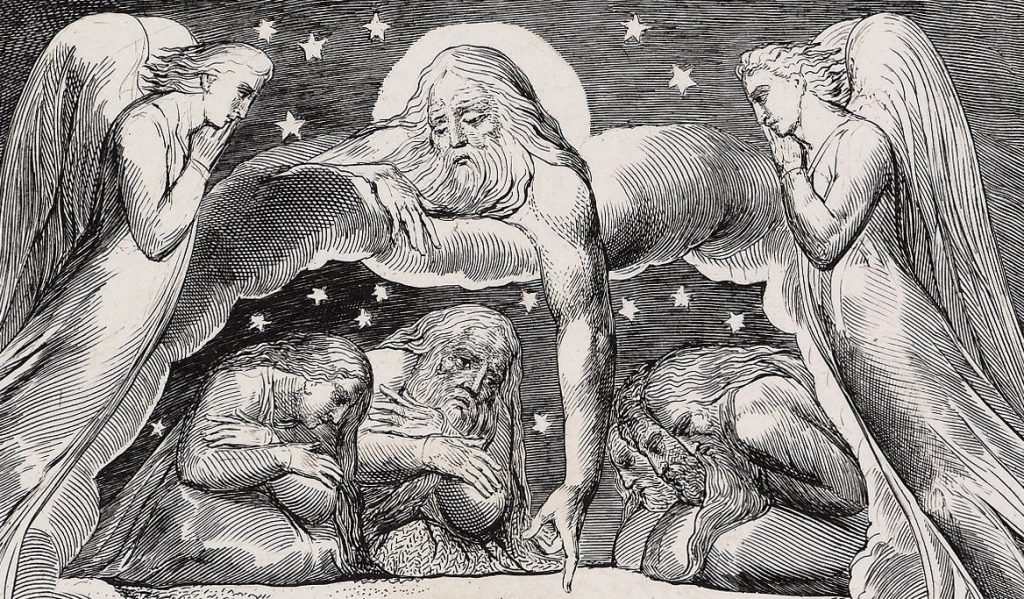

Last week I read and re-read the book of Job a few times, and then got to spend 12 hours discussing it with students. The reading is foundational, but the extended discussion time with bright young people is always illuminating. One of the things that this wild, strange book does, it seems to me, is direct us to make the distinction Sokolowski is talking about.

Here’s how the book of Job presents God in a way that has unique power to disclose the distinction between God and creation. After a few verses introducing us to Job’s initial situation, the opening scene takes us straight into the presence of the LORD, where “the sons of God” are coming before him. We are not given any details of the setting; the furniture is not described. We are not quite told when this occurs; it is on a “day.”

This abrupt introduction to the divine presence is not the opened heaven of apocalyptic vision; the word “heaven” is not even used to give us something to hold on to. It is also not apocalyptic in the sense of revealing something eschatological. In the form of its presentation, it is instead protological (a teaching about how things begin)): it shows what happened before the events on earth which we are about to read. The opening scene is even etiological (a teaching about what invisible forces caused a set of observed events).

Famously, Satan “also” is among the sons of God, and the LORD engages him in a brief interview, which is repeated with new developments on another day. The result is the affliction that plunges Job into perplexity and lament, calling forth the speeches of his friends and the character Elihu, and Job’s own intermittent self-defense.

Thus far the opening. It is beyond strange; not quite like anything else in the Bible; not introduced with any establishing information that we would like to have, and then dropped altogether once the main business of the book of Job begins. Conventional storytelling would suggest that a story with such a striking opening should also close with a return to that initial scene. Parentheses opened in this manner ought to be closed in a like manner. But no such conclusion waits for the reader at the end of the the book of Job. We do not return to whatever that heavenly throne room was (note that none of these helpful terms –heaven, throne– are the ones the book of Job uses); we do not hear again those voices from the divine council (also not Job words). We do not return to the presence of the LORD to overhear him negotiating with Satan about what is going on on the earth where he has been walking to and fro, up and down.

We can call the opening scene of the book of Job mythological without any prejudice against its possible historicity (we know too little about it to dogmatically declare it unhistorical). It is mythological in its narrative structure, in presenting a story about what happened in the divine realm that caused events to go a certain way in the earthly realm. It has the shape of mythological narrative in that it switches back and forth from the realm of the gods to the realm of humans. Ancient Near Eastern parallels would be the most informative comparisons, but readers of Homer can immediately see that the editorial maneuver of cross-cutting from the world above to the world below provides the same powerful narrative effects.

The opening gambit of the book of Job is therefore daring and even risky. An incautious reader could easily take it to be the story of what happens in the part of the world that is way up high, in the heaven part of heaven-and-earth (not a prominent Job phrase, by the way). It’s possible, in other words, to enter into the story of the book of Job without making the radical distinction that Sokolowski talks about. You might read the first two chapters of Job and imagine the LORD to be just as transcendent as Zeus among the Olympians, or of Plato’s mirrored realm of being. But that’s not transcendent enough; it’s the sham transcendence of etiological myth or a philosophical account of the world’s depth dimension; it’s a just-so story that exists to answer the all-too-human question of suffering.

But instead of bringing the reader back to that opening situation to tie up loose ends and assure us that all is well in the double-decker universe with a top floor and a bottom floor, the book of Job does something different.

Crazy different.

Dump-a-bucket-of-what-the-heck different.

Giant slab of sheer alterity different.

In-your-face “where were you when I laid the foundations” different, with a shot of Behemoth and a chaser of Leviathan.

The LORD suddenly speaks from the whirlwind (what whirlwind? where? how am I supposed to picture this?). He enters into an unequal dialogue with Job and puts to him a series of questions that are simultaneously unanswerable and obviously rhetorical. He speaks of the cosmos. Instead of discoursing directly about himself, the LORD subjects Job to a series of questions about the natural world. Of course he indicates at numerous points that he is above the cosmos, but the bulk of his speech is devoted to an account of the complex, manifold mystery of the world itself with all its regions of unknowability and awesomeness.

It’s not even all uniformly awesome, though: it includes the mountains and the stars, but also ostriches who God made stupid on purpose, which is a peculiar point to bring up in a speech that frequently seems like the poetic version of an intelligent design argument. I fully expect that on judgment day, many mouths will be shut by the LORD’s pointed query, suitably inscrutable in the ESV’s rendering, “The wings of the ostrich wave proudly, but are they the pinions and plumage of love?”² And just when the speech has made its tour from the most fundamental, elemental realities down to the manic zoo of biodiversity, the LORD takes a deep breath, lets Job respond briefly, and then concludes his speech with a sprawling coda about land monsters and sea monsters. Any fake god with a mythological carriage and some sham transcendence could huff and puff about his exaltedness. The true God shows Job a nature documentary in which he is not even the Attenborough voice-over, but something even more radically distinct.

Thus speaks the LORD, from the whirlwind (whatever and wherever that is), with no sons of God around and no Satan to interview. Thus speaks the LORD in a way that serenely disregards the narrative frame, declines to even nod in the direction of mythological trappings, and can’t be mapped or filmed or contextualized or diagrammed. Where we would expect to close the parentheses on the opening vignette, we instead get the voice, the utterance, of the biblical God who is so transcendent that he transcends transcendence. Instead of the other bookend we have the end of the book, with the verbal self-presencing of God who makes himself, and the distinction between himself and all things, known by heaving all things into the crushing awareness, and the implicated self-awareness, of his beloved servant, the righteous, fuddled Job who says the true thing about God.

The leap from the God of the opening chapters to the God of the final speech is a vast leap. If the opening chapters could have been assimilated to the narrative structures of myth, the final chapters cannot. Though lot of other things are going on in the book of Job (I lay my hand over my blog post), the invitation to move from the story of chapter 1 to the speech of chapter 38 is the invitation to acknowledge the fundamental biblical distinction which has to be known and experienced if there is to be faith in God.

_______________________

¹Sokolowski, The God of Faith and Reason: Foundations of Christian Theology (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1995), p. x in the preface to the new edition.

²Job 39:13, ESV. I do not know. I just do not know if they are the pinions and plumage of love. Frankly, sir, and with all due respect, I am not even quite sure what you are asking me. It’s probably my fault.