Several years ago I preached a sermon on Joshua 9, a chapter my Bible titles, “The Gibeonite Deception.” The story tells how the Israelites, fresh from their initial victories over the Canaanites at Jericho and Ai, were tricked into making covenant with the people from the city of Gibeon. The Gibeonites were Hivites (Josh 9:7), one of the Canaanite people groups God had singled out when he commanded the people of Israel, “You shall make no covenant with them” (Deut 7:1-2). Unlike the cities outside the borders of the promised land, God commanded that the Canaanite cities like Gibeon should be kharam-ed, put under a ban of complete destruction (Deut 20:10-18).

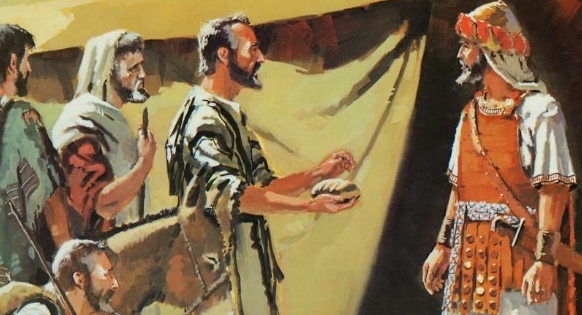

The Gibeonites may have been aware of God’s command because they came up with an elaborate ruse to fool the Israelites into thinking that they were not from Canaan. When the Gibeonites heard that the Israelite army was approaching, rather than harness their chariots and sharpen their swords, they “took worn out sacks for their donkeys, and wineskins, worn-out and torn and mended, with worn-out patched sandals on their feet, and worn-out clothes;” they made sure “all their provisions were dry and crumbly” (Josh 9:4-5). They went to the Israelites, told them they had come from a distant country, and asked them to make a covenant. At first the Israelites were wary, but the crumbly provisions were enough to convince them that it was safe to make a covenant.

The text says, “The [Israelites] took some of the provisions, but they did not ask counsel from the LORD” (9:14). There’s a good sermon in that verse: one that would remind us that we can’t always trust our natural senses, but need supernatural direction from God. Man shall not make decisions based on crumbly bread alone.

However, that was not point of my sermon, and I don’t think it’s the central message of the passage. My Old Testament professor at Asbury Seminary, Lawson Stone, has pointed out that Joshua 9-11 does not focus on the actions of the Israelites, but the re-actions of the Canaanites. The subsections show a repeated pattern: the various Canaanites 1) hear their predicament, 2) respond, and 3) reap the consequences of their response. The section begins: “As soon as all the kings who were beyond the Jordan…heard [about the destruction of Jericho and Ai], they gathered together as one to fight against Joshua and Israel. But when the inhabitants of Gibeon heard… they on their part acted with cunning” (9:1-4). The same news prompts two different responses, two different strategies.

The Gibeonites “on their part, acted with cunning,” or as the King James says, “They did work wilily.” The wily work of the Gibeonites has occasioned a considerable amount of ethical debate. Is deception ever an acceptable means to achieve a desired end? More pointedly, could it ever be right to trick God’s people into transgressing his explicit command, like Delilah tricked Samson? The text gives little help in answering these difficult ethical questions. The only help it offers for judging the scheme is its presentation the outcome.

The difference between the outcome of the Gibeonites’ choice (to act with cunning) and the outcome of other Canaanites’ choice (to unite and fight) is stark. Although the Gibeonites’ choice resulted in perpetual servitude to the Israelites—they became “cutters of wood and drawers of water” (9:27)—at least at the end of the day they were all alive. The concluding summary of Joshua 9-11 contrasts the fate of Gibeon, the only city of the Canaan to make peace with the Israelites, with the fates of all the other cites, whose choice to fight the Israelites, meant that they would be kharam-ed, that they would “receive not mercy but be destroyed” (11:20).

The success that followed the Gibeonites’ chosen path is underscored by the story that immediately follows the story of how their deception secured a covenant. When the other Canaanites heard about their peace treaty with Israel, five Canaanite kings (in keeping with their chosen strategy) “gathered their forces and went up with all their armies and encamped against Gibeon and made war against it” (10:5.) In response, “the LORD threw [their armies] into a panic” then “threw down great stones from heaven on them,” and then caused the sun and moon to stand still in the sky to allow the remnants of the army to be wiped out (10:6-15). The five defeated kings, who had hidden in a cave, were captured, executed, and hanged on five trees (10:16-28). It’s hard to imagine how the Gibeonites’ choice could receive more ample affirmation.

The divine protection that came from the Gibeonites’ covenant with Israel is evidence that whether or not their scheme was ethical, it was unquestionably successful. That the text intends to emphasize the efficacy of their choice—rather than its morality—can be further supported by considering the significance of the Hebrew word it uses to characterize their choice. The word ‘armah translated “cunning” or “wili[ness]” in reference to the Gibeonites, also occurs in the book of Proverbs where it is routinely translated “prudence.” The book begins with the promise the proverbs will “give prudence to the simple”: it will help people to stop acting like idiots and start making some smart choices. ‘Armah is not primarily helpful for becoming holy or righteous; it’s helpful for becoming successful or prosperous. It’s for avoiding pitfalls and making the most out of opportunities. It’s for reading a situation and making the appropriate response. The cunning Gibeonites made an appropriate response to the Israelite’s divinely-aided destruction of Jericho: do whatever it takes to make peace with the Israelites. The Canaanites decision—fight the Israelites—showed that they lacked ‘armah; they were idiots.

A translation of ‘armah that would work in both Joshua 9 and Proverbs is “shrewdness.” It splits the difference between the positive connotation of “prudence” and the negative connotation of “cunning.” Shrewdness includes the perceptiveness to correctly size up a situation, the wisdom to discern the most promising option, the cleverness to devise an effective plan of action, and the pluck and resolve necessary to put it into action while there’s still time.

Shrewdness is the quality that distinguishes the Gibeonites and also the main character in one of the stories of Jesus, the one often called “the parable of the dishonest manager.” The manager hearing that his boss is about to fire him, devises a cunning scheme. He offers everyone who owes the boss money to cut their loan in half. That way, once he’s fired, he’ll have plenty of people who owe him a favor.

There’s no question that this is an unethical scheme. However, in the surprising conclusion of the story, the boss praises the manager for his shrewdness. You can imagine the boss calling the manager into his office. “You lowdown scoundrel,” he says, “You’re about to run this business into the ground.” Then shaking his head with a grin he says, “Still I gotta hand it to you. For devious brilliance and sheer audacity, this beats all.” Like the Gibeonites, the dishonest manager understood that he was in a desperate situation, cooked up a shrewd scheme, and went all out in his last ditch attempt to avoid the coming catastrophe.

Jesus concludes his sermon marveling that “the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their generation than the sons of the light” (Luke 16:8). When it comes to shrewdness, we sons of the light have something to learn from the wily Gibeonites.