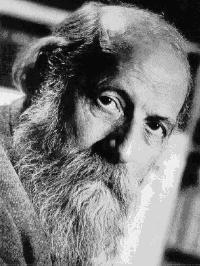

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish philosopher who did a great deal to put classic documents of Hasidic tradition into wider circulation. He is most famous for his 1923 book I and Thou.

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish philosopher who did a great deal to put classic documents of Hasidic tradition into wider circulation. He is most famous for his 1923 book I and Thou.

I and Thou is a remarkable book, a masterpiece of simplicity and direct communication. I don’t know if it will ever seem as important again as it did for a while in the 1960s, when $5 Scribner paperback copies of it blanketed college campuses and everybody had to footnote in every discussion. But it has all the marks of a classic text, a great book: It draws you in with an immediacy that has you thinking the author’s thoughts along with him before you can stop yourself. By the time you back off and get some critical distance, you realize you have to start using big words like existentialism and dialogical personalism to describe the thoughts you’ve been thinking.

But none of those big words were what drew you in. I and Thou reads more like poetry or mysticism than philosophy. Here are the opening statements of the book:

To man the world is twofold, in accordance with his twofold attitude.

The attitude of man is twofold, in accordance with the twofold nature of the primary words which he speaks.

The primary words are not isolated words, but combined words.

The one primary word is the combination I-Thou.

The other primary word is the combination I-It; wherein, without a change in the primary word, one of the words He and She can replace It.

Hence the I of man is also twofold.

For the I of the primary word I-Thou is a different I from that of the primary word I-It.

Primary words do not signify things, but they intimate relations.

Primary words do not describe something that might exist independently of them, but being spoken they bring about existence.

Primary words are spoken from the being.

If Thou is said, the I of the combination I-Thou is said along with it.

If It is said, the I of the combination I-It is said along with it.

The primary word I-Thou can only be spoken with the whole being.

The primary word I-It can never be spoken with the whole being.

What is that, in 1923? Existentialism is the easiest answer, but the irreducible personalism in it has proven much more helpful for Christian thinkers than the limited usefulness of existential categories. In fact, Walter Kaufmann once briefly explored this question of whether Buber should be called existentialist:

If we find the heart of existentialism in the protest against systems, concepts, and abstractions, coupled with a resolve to remain faithful to concrete experience and above all to the challenge of human existence –should we not find in that case that Kierkegaard and Jaspers, Heidegger and Sartre had all betrayed their own central resolve? That they had all become enmeshed in sticky webs of dialectic that impede communication? That the high abstractness of their idiom and their strange addiction to outlandish concepts far surpassed the same faults in Descartes or Plato? That not one of them was able any more to listen to the challenge of another human reality as it found expression in a text? And that their writings have, without exception, become monologues? (Kaufmann, Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre)

And then, Kaufmann concludes with my favorite sentence about Buber: “In reality there is only one existentialist, and he is no existentialist, but Martin Buber.”