“You Christians seem to have a religion that makes you miserable. You are like a man with a headache. He does not want to get rid of his head, but it hurts him to keep it. You cannot expect outsiders to seek very earnestly for anything so uncomfortable.”

“You Christians seem to have a religion that makes you miserable. You are like a man with a headache. He does not want to get rid of his head, but it hurts him to keep it. You cannot expect outsiders to seek very earnestly for anything so uncomfortable.”

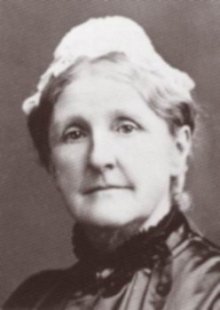

When Hannah Whitall Smith (1832-1911) heard someone making this accusation against Christianity, she “saw, as in a flash, that the religion of Christ ought to be, and was meant to be, to its possessors, not something to make them miserable, but something to make them happy; and I began then and there to ask the Lord to show me the secret of a happy Christian life.”

Smith reports this event on the first page of her perennially best-selling book The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life (1875, revised and expanded 1888). It’s a book that has gone through dozens of editions and sold at least two million copies. The book is actually a collection of short articles she had already written and published in a journal over the previous years, but in their compiled form they became a classic text of a certain kind of nineteenth century evangelicalism. Smith’s recipe is a cup of Wesleyan Holiness teaching, a few teaspoons of the Higher Life, baste with Keswick terminology, and all baked in the Quakerism of Smith’s family origins. She wants to give her readers a taste of something greater than their current experience of salvation:

Did being made “more than conquerors through Him that loved us” mean constant defeat and failure? Does being “saved to the uttermost” mean the meager salvation we see manifested among us now? … Settle down on this one thing, that Jesus came to save you now, in this life, from the power and dominion of sin, and to make you more than conquerors through His power. If you doubt this, search your Bible… It is a fact sometimes overlooked that, in the declarations concerning the object of the death of Christ, far more mention is made of a present salvation from sin, than of a future salvation in a heaven beyond…

Smith has a lot to commend her as a writer: She exudes confidence, she is sensitive to spiritual suffering, she is fluent in the phrases of Scripture, and she writes with clarity and simplicity. She wants to be understood, so she never hems and haws. First she states her main thesis, then she illustrates it. The life she wants more Christians to experience is like this:

Its chief characteristics are an entire surrender to the Lord, and a perfect trust in Him, resulting in victory over sin, and inward rest of soul; and it differs from the lower range of Christian experience in that it causes us to let the Lord carry our burdens and manage our affairs for us, instead of trying to do it ourselves.

and then the unforgettable illustration:

Most Christians are like a man who was toiling along the road, bending under a heavy burden, when a wagon overtook him, and the driver kindly offered to help him on his journey. He joyfully accepted the offer but when seated in the wagon, continued to bend beneath his burden, which he still kept on his shoulders. “Why do you not lay down your burden?” asked the kind-hearted driver. ” Oh!” replied the man, “I feel that it is almost too much to ask you to carry me, and I could not think of letting you carry my burden too.” And so Christians, who have given themselves into the care and keeping of the Lord Jesus, still continue to bend beneath the weight of their burdens, and often go weary and heavy-laden throughout the whole length of their journey.

Hannah Whitall Smith’s The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life is a long-standing best-seller, so it’s worth reading for historical interest if nothing else. As a wake-up call to remind you that the Christian life does not have to be glum, it can be a beneficial read. Smith writes in sweeping, general statements, so readers with many different presuppositions can find something familiar in The Christian’s Secret.

But there are numerous unfortunate expressions in the book, and it is susceptible to dangerous interpretations: In her insistence on our passivity in receiving God’s gifts, Smith often sounds like a “let go and let God’ quietist. She tends towards an elitist attitude that divides Christians into those who really “get it” and the multitude who are just saved. Her presentation of “full salvation” can sound too much like a wonderful product for your fulfilling lifestyle. B. B. Warfield thought the book was typical of the “ingrained eudaemonism of the Higher Christian Life movement” which was “preoccupied with the pursuit of happiness.”

And even as The Christian’s Secret was racking up its huge sales in the wild final decades of the nineteenth century, Hannah Whitall Smith had moved on to a new issue in her spirituality. Always given to flashes of revelation and inner illuminations, Smith became certain, in that Quakerish inner-light sort of way, that God would save everyone. She was eager to spread her newfound universalism, and her autobiographical The Unselfishness of God and How I Discovered It (1903) chronicled the story of her increasing delusion as she self-consciously re-imagined God in her own image. Smith’s later work is all cautionary tale, and her life was blighted by her husband’s misconduct and her own intransigence. But Smith wrote The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life at an early point, before her idiosyncrasies reached escape velocity and took her off into weirdness. She achieved, in that book, a tone of voice that explains how such a deeply flawed book has nevertheless managed to do a great deal of good for some readers. Christians’ Secret channeled a powerful stream of the evangelical spirituality that flowed from the revivals of the nineteenth century. If it carried (as Warfield warned) much of what was wrong with the revival spirit, it also transmitted some of what was right.