George Steiner published a book back in 1959 called Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old Criticism. Like all of Steiner’s books, this first publication of his ranges over a lot of territory and sheds light all around. As with most of Steiner’s books, I had to read only the parts I could understand, skipping some sections in which he seemed to be saying interesting things about books I’d never read or even heard of. He’s a tough read, but worth the effort. Steiner has never been guilty of churning out criticism just to keep the academic presses rolling or to keep his career going. “Literary criticism,” he says on the first page of this first book, “should arise out of a debt of love.” He writes about books that have seized his imagination and changed him. “To borrow an image from another domain: he who has truly apprehended a painting by Cezanne will thereafter see an apple or a chair as he had not seen them before. Great works of art pass through us like storm-winds, flinging open the doors of perception, pressing upon the architecture of our beliefs with their transforming powers. We seek to record their impact, to put our shaken house in its new order.”

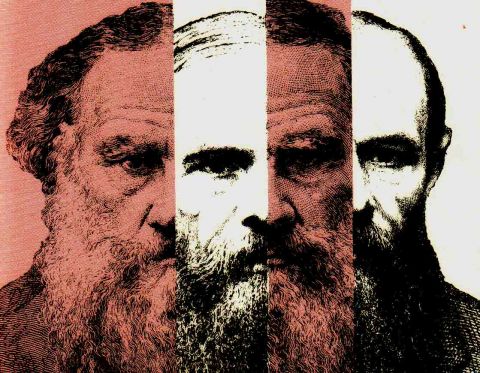

In Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, Steiner writes out of love for these two great Russian novelists, but his point of departure is the observation that the two authors are fundamentally opposed in all the ways that matter most. He believes they can best be understood by contrast, by putting them into an imaginative dialogue with each other, and the book is a long and thoughtful exercise in reading T&D against each other. As I said above, there are long passages of the book that I’ll leave only skimmed until I’ve managed to read more of the primary texts Steiner is analyzing –not just from Tolstoyevsky and the other great Russian literary exports, but from the rest of the literature of the western world. Steiner puts his subjects in the broadest possible context, ultimately explaining Tolstoy and Dostoevsky by reference to Homer and Shakespeare! But I have noticed the same thing Steiner noticed, that there is a fundamental contrast between these two big Russian novelists.

In fact, I have long thought that there are basically two kinds of people in the world: Tolstoy people and Dostoevsky people. But Steiner says it better, and says more:

He quotes the Russian philosopher Berdiaev as saying, “It would be possible to determine two patterns, two types among men’s souls, the one inclined toward the spirit of Tolstoy, the other toward that of Dostoevsky.” Steiner agrees: “Experience bears him out. A reader may regard them as the two principle masters of fiction –that is to say, he may find in their novels the most inclusive and searching portrayal of life. But press him closely and he will choose between them. If he tells you which he prefers and why, you will, I think, have penetrated into his own nature. The choice between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky foreshadows what existentialists would call un engagement; it commits the imagination to one or the other of two radically opposed interpretations of man’s fate, of the historical future, and of the mystery of God.”

A brief summary can’t do justice to the extended analysis Steiner provides, but here is part of his own conclusion:

Thus, even beyond their deaths, the two novelists stand in contrariety. Tolstoy, the foremost heir to the traditions of the epic, Dostoevsky, one of the major dramatic tempers after Shakespeare; Tolstoy, the mind intoxicated with reason and fact; Dostoevsky, the contemner of rationalism, the great lover of paradox; Tolstoy, the poet of the land, of the rural setting and the pastoral mood; Dostoevsky, the arch-citizen, the master-builder of the modern metropolis in the province of language; Tolstoy, thirsting for the truth, destroying himself and those about him in excessive pursuit of it; Dostoevsky, rather against the truth than against Christ, suspicious of total understanding and on the side of mystery; Tolstoy, ‘keeping at all times,’ in Coleridge’s phrase, ‘in the high road of life’; Dostoevsky, advancing into the labyrinth of the unnatural, into the cellerage and morass of the soul; Tolstoy, like a colossus bestriding the palpable earth, evoking the realness, the tangibility, the sensible entirety of concrete experience; Dostoevsky, always on the edge of the hallucinatory, of the spectral, always vulnerable to daemonic intrusions into what might prove, in the end, to have been merely a tissue of dreams; Tolstoy, the embodiment of health and Olympian vitality; Dostoevsky, the s um of energies charged with illness and possession; Tolstoy, who saw the destinies of men historically and in the stream of time; Dostoevsky, who saw them contemporaneously and in the vibrant stasis of the dramatic moment; Tolstoy, borne to his grave in the first civil burial ever held in Russia; Dostoevsky, laid to rest in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky monastery in St. Petersburg amid the solemn rites of the Orthodox Church; Dostoevsky, pre-eminently the man of God; Tolstoy; one of His secret challengers.

Steiner’s summary attempts to be even-handed, and he obviously adores the works of both authors. But I have a guess which kind of person Steiner is.