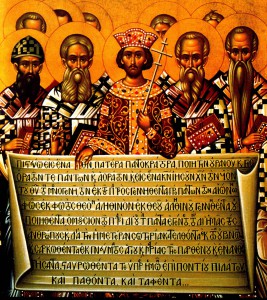

The Council of Nicaea opened on this day, May 20, 325. What happened at that first ecumenical council? What was at stake theologically? The narrative of events and players is available elsewhere, but here is an account of the doctrinal dynamics.

The Council of Nicaea opened on this day, May 20, 325. What happened at that first ecumenical council? What was at stake theologically? The narrative of events and players is available elsewhere, but here is an account of the doctrinal dynamics.

The council of Nicaea was a response to the challenge of Arianism. In the history books on Christian doctrine, Arianism has often been presented as a kind of outside force invading the Church. That was Athanasius’ view, for instance, and it is certainly true if you view things from the perspective of the eternal truth of the gospel. But in the last several decades, scholars have argued for a more sympathetic view of Arianism as a logical development of certain elements already contained in the Christian theological tradition. Modern scholars with their unshakable hermeneutic of suspicion are always keen to rehabilitate heretics, of course, but in this case they have rightly identified how it must have looked to the actual participants. The thinkers of the fourth century did not inherit an obvious and pristine doctrinal tradition. The stream had become muddied in various ways. Everybody was quoting the second-century theologian Origen, but Origen had left in his writings as many terrible errors as he had solid expositions of the faith. By the fourth century, there was a lot of cleaning up to do. The work of the Nicene theologians can be seen as a kind of Reformation.

Nicaea was therefore a conflict of Christian tradition with itself, or between diverse strands within the theologies available in the Christian tradition. The conflict itself clarified much that had been left ambiguous in previous theology, and in order to maintain the central claims of Christian doctrine, the Nicene theologians had to make two decisive changes in the tradition: on the one hand, they had to reject strands of theology that had previously had a good claim to being considered catholic and authoritative; and on the other hand they had to make decisive new statements in the realm of the metaphysical implications of doctrine.

Arianism was a fairly diverse and diffuse movement, whose adherents disagreed among themselves and whose ideas developed over the course of time. But many of its basic ideas were consistent from Arius (317) until at least Eunomius (died 393), and can be summarized in a few points: God the Father was not always Father, but became so when he created the Logos, his Son. There is a sense in which Logos is eternal and immanent to God as divine Reason; but the distinct being known as the Logos, with whom we have to do, is given this name in a derived sense. This Logos was created before time, and then time was created through him. The Logos came into being in order to make the creation of the world possible. The Son of God is changeable by nature, but stable by divine grace. Trinitarian language such as the baptismal formula in Matthew 28 is to be understood as describing three essentially dissimilar beings: the high God, the created Logos, and the divine Spirit at work among us.

Arianism can be seen as an attempt to do justice to the full involvement of the Logos in the life and sufferings of Jesus Christ; its point of departure may be a soteriological vision of a redeemer who wins redemption for himself and thereby serves as our model in all things. Athanasius and the other Nicene theologians perceived it as a lethal threat to the Christian idea of revelation and salvation, however, because it offered an inadequate interpretation of the relationship between the Logos and God. It attempted to frame a theology by using the neoplatonic ideas of a graduated divinity, with an utterly transcendent One God and a series of ontological emanations descending therefrom. The creative (and in the background is the demiurge, the creator-craftsman from the platonic tradition) Logos, incarnate in Jesus Christ, is divine in a qualified, relative sense. Over against this, Athanasius and the Nicene theology insisted on an absolute distinction between the creator and creation, with no middle ground. The mediator could not be a metaphysical tertium quid, a “third thing” between God and man, but had to be fully God and fully human.

Nicene theology thus rejected certain “easy answers” offered by the hellenistic philosophical categories available at the time. In doing so, Nicene theology drew the metaphysical implications of its revelational and soteriological claims. Athanasius in particular perceived that if Christ truly reveals God and reconciles us to God, then Christ must be fully divine, must in fact be homoousios, of one essence, with God. Many theologians in the fourth century continued to be squeamish about applying this metaphysical “substance” language to God and Christ, but the strategy of Nicaea was to adopt it as a necessary implication of Christian commitments. Once Arius had raised the ontological question so forcefully, it could only be answered in ontological terms. Earlier theologians, even one as great as Irenaeus, did not use such explicitly ontological terms to describe the Son’s relationship to the Father; nor did they use explicitly ontological terms to deny the Son’s unity with the Father. Arius started it. When he innovated, Nicaea innovated right back. You might be able to do theology without the help of categories like substance, but once you invoke them, there are wrong answers and right answers.

In making this advance, Athanasius and the other Nicene theologians also rejected some important traditional elements of pre-Nicene theology. There had always been a kind of naive subordinationism in the more economic theologies of the first three centuries. Justin and the other apologists clearly saw the Logos as the God (or the part of God) who was able to condescend to creation and redemption by virtue of being lower on the scale of being. Even Irenaeus was not free of this suggestion. Parts of Origen’s many-sided systematic thought clearly limited the Son to created status, while at the same time affirming his eternal generation. Tertullian, by contrast, maintained the divinity of Christ not on the basis of eternal generation (which he rejected), but on the basis of shared substance (conceived in refined materialistic Stoic terms).

Subordinationism had a legitimate claim to being in some sense traditional catholic doctrine. Athanasius saw that it had to be rejected, and his theology was an attempt to retain the core of the theological tradition while stripping away any possibility of ontological subordinationism. Thus the Son is homoousios with the Father (later this same argument was applied to the Spirit), and was eternally generated rather than called forth for the events of creation and redemption. The Logos theology, which had from the start carried misleading ontological and cosmological suggestions, was redefined and domesticated by Athanasius. “Logos” was subordinated to “Son” as the interpretive key to the identity of Christ. All of this was carried out without explicit condemnation of the patristic authors who Athanasius wanted to retain as orthodox teachers; not even Origen was spoken poorly of by Athanasius, in spite of the obvious rejection of elements of his thought which the Arians championed.

In summary, what was at stake at Nicaea was, according to Athanasius, salvation. The Nicene strategy for defending the soteriological claim of Christian theology called for a new development of doctrine, a repudiation of certain contradictory elements of the tradition, a refining of terminological conventions, and a concentration of Christian doctrine.